Project Gutenberg's Critical & Historical Essays, by Edward MacDowell

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Critical & Historical Essays

Lectures delivered at Columbia University

Author: Edward MacDowell

Editor: W. J. Baltzell

Release Date: July 24, 2005 [EBook #16351]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK CRITICAL & HISTORICAL ESSAYS ***

Produced by David Newman, Daniel Emerson Griffith and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

The present work places before the public a phase of the professional activity of Edward MacDowell quite different from that through which his name became a household word in musical circles, that is, his work as a composer. In the chapters that follow we become acquainted with him in the capacity of a writer on phases of the history and æsthetics of music.

It was in 1896 that the authorities of Columbia University offered to him the newly created Chair of Music, for which he had been strongly recommended as one of the leading composers of America. After much thought he accepted the position, and entered upon his duties with the hope of accomplishing much for his art in the favorable environment which he fully expected to find. The aim of the instruction, as he planned it, was: “First, to teach music scientifically and technically, with a view to training musicians who shall be competent to teach and compose. Second, to treat music historically and æsthetically as an element of liberal culture.” In carrying out his plans he conducted a course, which, while “outlining the purely technical side of music,” was intended to give a “general idea of music from its historical and æsthetic side.” Supplementing this, as an advanced course, he also gave one which took up the development of musical forms, piano music, modern orchestration and symphonic forms, impressionism, the relationship of music to the other arts, with much other material necessary to form an adequate basis for music criticism.

It is a matter for sincere regret that Mr. MacDowell put in permanent form only a portion of the lectures prepared for the two courses just mentioned. While some were read from manuscript, others were given from notes and illustrated with musical quotations. This was the case, very largely, with the lectures prepared for the advanced course, which included extremely valuable and individual treatment of the subject of the piano, its literature and composers, modern music, etc.

A point of view which the lecturer brought to bear upon his subject was that of a composer to whom there were no secrets as to the processes by which music is made. It was possible for him to enter into the spirit in which the composers both of the earlier and later periods conceived their works, and to value the completed compositions according to the way in which he found that they had followed the canons of the best and purest art. It is this unique attitude which makes the lectures so valuable to the musician as well as to the student.

The Editor would also call attention to the intellectual qualities of Mr. MacDowell, which determined his attitude toward any subject. He was a poet who chose to express himself through the medium of music rather than in some other way. For example, he had great natural facility in the use of the pencil and the brush, and was strongly advised to take up painting as a career. The volume of his poetical writings, issued several years ago, is proof of his power of expression in verse and lyric forms. Above these and animating them were what Mr. Lawrence Gilman terms “his uncommon faculties of vision and imagination.” What he thought, what he said, what he wrote, was determined by the poet's point of view, and this is evident on nearly every page of these lectures.

He was a wide reader, one who, from natural bent, dipped into the curious and out-of-the-way corners of literature, as will be noticed in his references to other works in the course of the lectures, particularly to Rowbotham's picturesque and fascinating story of the formative period of music. Withal he was always in touch with contemporary affairs. With the true outlook of the poet he was fearless, individual, and even radical in his views. This spirit, as indicated before, he carried into his lectures, for he demanded of his pupils that above all they should be prepared to do their own thinking and reach their own conclusions. He was accustomed to say that we need in the United States, a public that shall be independent in its judgment on art and art products, that shall not be tied down to verdicts based on tradition and convention, but shall be prepared to reach conclusions through knowledge and sincerity.

That these lectures may aid in this splendid educational purpose is the wish of those who are responsible for placing them before the public.

W. J. BALTZELL.

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

|---|---|---|

| I. | The Origin of Music | 1 |

| II. | Origin of Song vs. Origin of Instrumental Music | 16 |

| III. | The Music of the Hebrews and the Hindus | 32 |

| IV. | The Music of the Egyptians, Assyrians and Chinese | 42 |

| V. | The Music of the Chinese (continued) | 54 |

| VI. | The Music of Greece | 69 |

| VII. | The Music of the Romans—the Early Church | 90 |

| VIII. | Formation of the Scale—Notation | 106 |

| IX. | The Systems of Hucbald and Guido d'Arezzo—the Beginning of Counterpoint | 122 |

| X. | Musical Instruments—Their History and Development | 132 |

| XI. | Folk-Song and its Relation to Nationalism in Music | 141 |

| XII. | The Troubadours, Minnesingers and Mastersingers | 158 |

| XIII. | Early Instrumental Forms | 175 |

| XIV. | The Merging of the Suite into the Sonata | 188 |

| XV. | The Development of Pianoforte Music | 199 |

| XVI. | The Mystery and Miracle Play | 205 |

| XVII. | Opera | 210 |

| XVIII. | Opera (continued) | 224 |

| XIX. | On the Lives and Art Principles of Some Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Composers | 236 |

| XX. | Declamation in Music | 254 |

| XXI. | Suggestion in Music | 261 |

Darwin's theory that music had its origin “in the sounds made by the half-human progenitors of man during the season of courtship” seems for many reasons to be inadequate and untenable. A much more plausible explanation, it seems to me, is to be found in the theory of Theophrastus, in which the origin of music is attributed to the whole range of human emotion.

When an animal utters a cry of joy or pain it expresses its emotions in more or less definite tones; and at some remote period of the earth's history all primeval mankind must have expressed its emotions in much the same manner. When this inarticulate speech developed into the use of certain sounds as symbols for emotions—emotions that otherwise would have been expressed by the natural sounds occasioned by them—then we have the beginnings of speech as distinguished from music, which is still the universal language. In other words, intellectual development begins with articulate speech, leaving music for the expression of the emotions.

To symbolize the sounds used to express emotion, if I may so put it, is to weaken that expression, and it would naturally be the strongest emotion that would first feel the inadequacy of the new-found speech. Now what is mankind's strongest emotion? Even in the nineteenth century Goethe could say, “'Tis fear that constitutes the god-like in man.” Certainly before the Christian era the soul of mankind had its roots in fear. In our superstition we were like children beneath a great tree of which the upper part was as a vague and fascinating mystery, but the roots holding it firmly to the ground were tangible, palpable facts. We feared—we knew not what. Love was human, all the other emotions were human; fear alone was indefinable.

The primeval savage, looking at the world subjectively, was merely part of it. He might love, hate, threaten, kill, if he willed; every other creature could do the same. But the wind was a great spirit to him; lightning and thunder threatened him as they did the rest of the world; the flood would destroy him as ruthlessly as it tore the trees asunder. The elements were animate powers that had nothing in common with him; for what the intellect cannot explain the imagination magnifies.

Fear, then, was the strongest emotion. Therefore auxiliary aids to express and cause fear were necessary when the speech symbols for fear, drifting further and further away from expressing the actual thing, became words, and words were inadequate to express and cause fear. In that vague groping for sound symbols which would cause and express fear far better than mere words, we have the beginning of what is gradually to develop into music.

We all know that savage nations accompany their dances by striking one object with another, sometimes by a clanking of stones, the pounding of wood, or perhaps the clashing of stone spearheads against wooden shields (a custom which extended until the time when shields and spears were discarded), meaning thus to express something that words cannot. This meaning changed naturally from its original one of being the simple expression of fear to that of welcoming a chieftain; and, if one wishes to push the theory to excess, we may still see a shadowy reminiscence of it in the manner in which the violinists of an orchestra applaud an honoured guest—perchance some famous virtuoso—at one of our symphony concerts by striking the backs of their violins with their bows.

To go back to the savages. While this clashing of one object against another could not be called the beginning of music, and while it could not be said to originate a musical instrument, it did, nevertheless, bring into existence music's greatest prop, rhythm, an ally without which music would seem to be impossible. It is hardly necessary to go into this point in detail. Suffice it to say that the sense of rhythm is highly developed even among those savage tribes which stand the lowest in the scale of civilization to-day, for instance, the Andaman Islanders, of whom I shall speak later; the same may be said of the Tierra del Fuegians and the now extinct aborigines of Tasmania; it is the same with the Semangs of the Malay Peninsula, the Ajitas of the Philippines, and the savages inhabiting the interior of Borneo.

As I have said, this more or less rhythmic clanking of stones together, the striking of wooden paddles against the side of a canoe, or the clashing of stone spearheads against wooden shields, could not constitute the first musical instrument. But when some savage first struck a hollow tree and found that it gave forth a sound peculiar to itself, when he found a hollow log and filled up the open ends, first with wood, and then—possibly getting the idea from his hide-covered shield—stretched skins across the two open ends, then he had completed the first musical instrument known to man, namely, the drum. And such as it was then, so is it now, with but few modifications.

Up to this point it is reasonable to assume that primeval man looked upon the world purely subjectively. He considered himself merely a unit in the world, and felt on a plane with the other creatures inhabiting it. But from the moment he had invented the first musical instrument, the drum, he had created something outside of nature, a voice that to himself and to all other living creatures was intangible, an idol that spoke when it was touched, something that he could call into life, something that shared the supernatural in common with the elements. A God had come to live with man, and thus was unfolded the first leaf in that noble tree of life which we call religion. Man now began to feel himself something apart from the world, and to look at it objectively instead of subjectively.

To treat primitive mankind as a type, to put it under one head, to make one theorem cover all mankind, as it were, seems almost an unwarranted boldness. But I think it is warranted when we consider that, aside from language, music is the very first sign of the dawn of civilization. There is even the most convincingly direct testimony in its favour. For instance:

In the Bay of Bengal, about six hundred miles from the Hoogly mouth of the Ganges, lie the Andaman Islands. The savages inhabiting these islands have the unenviable reputation of being, in common with several other tribes, the nearest approach to primeval man in existence. These islands and their inhabitants have been known and feared since time immemorial; our old friend Sinbad the Sailor, of “Arabian Nights” fame, undoubtedly touched there on one of his voyages. These savages have no religion whatever, except the vaguest superstition, in other words, fear, and they have no musical instruments of any kind. They have reached only the rhythm stage, and accompany such dances as they have by clapping their hands or by stamping on the ground. Let us now look to Patagonia, some thousands of miles distant. The Tierra del Fuegians have precisely the same characteristics, no religion, and no musical instruments of any kind. Retracing our steps to the Antipodes we find among the Weddahs or “wild hunters” of Ceylon exactly the same state of things. The same description applies without distinction equally well to the natives in the interior of Borneo, to the Semangs of the Malay Peninsula, and to the now extinct aborigines of Tasmania. According to Virchow their dance is demon worship of a purely anthropomorphic character; no musical instrument of any kind was known to them. Even the simple expression of emotions by the voice, which we have seen is its most primitive medium, has not been replaced to any extent among these races since their discovery of speech, for the Tierra del Fuegians, Andamans, and Weddahs have but one sound to represent emotion, namely, a cry to express joy; having no other means for the expression of sorrow, they paint themselves when mourning.

It is granted that all this, in itself, is not conclusive; but it will be found that no matter in what wilderness one may hear of a savage beating a drum, there also will be a well-defined religion.

Proofs of the theory that the drum antedates all other musical instruments are to be found on every hand. For wherever in the anthropological history of the world we hear of the trumpet, horn, flute, or other instrument of the pipe species, it will be found that the drum and its derivatives were already well known. The same may be said of the lyre species of instrument, the forerunner of our guitar (kithara), tebuni or Egyptian harp, and generally all stringed instruments, with this difference, namely, that wherever the lyre species was known, both pipe and drum had preceded it. We never find the lyre without the drum, or the pipe without the drum; neither do we find the lyre and the drum without the pipe. On the other hand, we often find the drum alone, or the drum and pipe without the lyre. This certainly proves the antiquity of the drum and its derivatives.

I have spoken of the purely rhythmical nature of the pre-drum period, and pointed out, in contrast, the musical quality of the drum. This may seem somewhat strange, accustomed as we are to think of the drum as a purely rhythmical instrument. The sounds given out by it seem at best vague in tone and more or less uniform in quality. We forget that all instruments of percussion, as they are called, are direct descendants of the drum. The bells that hang in our church towers are but modifications of the drum; for what is a bell but a metal drum with one end left open and the drum stick hung inside?

Strange to say, as showing the marvellous potency of primeval instincts, bells placed in church towers were supposed to have much of the supernatural power that the savage in his wilderness ascribed to the drum. We all know something of the bell legends of the Middle Ages, how the tolling of a bell was supposed to clear the air of the plague, to calm the storm, and to shed a blessing on all who heard it. And this superstition was to a certain extent ratified by the religious ceremonies attending the casting of church bells and the inscriptions moulded in them. For instance, the mid-day bell of Strasburg, taken down during the French Revolution, bore the motto

“I am the voice of life.”

Another one in Strasburg:

“I ring out the bad, ring in the good.”

Others read

“My voice on high dispels the storm.”

“I am called Ave Maria

I drive away storms.”“I who call to thee am the Rose of the World and am called Ave Maria.”

The Egyptian sistrum, which in Roman times played an important rôle in the worship of Isis, was shaped somewhat like a tennis racquet, with four wire strings on which rattles were strung. The sound of it must have been akin to that of our modern tambourine, and it served much the same purpose as the primitive drum, namely, to drive away Typhon or Set, the god of evil. Dead kings were called “Osiris” when placed in their tombs, and sistri put with them in order to drive away Set.

Beside bells and rattles we must include all instruments of the tambourine and gong species in the drum category. While there are many different forms of the same instrument, there are evidences of their all having at some time served the same purpose, even down to that strange instrument about which Du Chaillu tells us in his “Equatorial Africa”, a bell of leopard skin, with a clapper of fur, which was rung by the wizard doctor when entering a hut where someone was ill or dying. The leopard skin and fur clapper seem to have been devised to make no noise, so as not to anger the demon that was to be cast out. This reminds us strangely of the custom of ringing a bell as the priest goes to administer the last rites.

It is said that first impressions are the strongest and most lasting; certain it is that humanity, through all its social and racial evolutions, has retained remnants of certain primitive ideas to the present day. The army death reveille, the minute gun, the tolling of bells for the dead, the tocsin, etc., all have their roots in the attributes assigned to the primitive drum; for, as I have already pointed out, the more civilized a people becomes, the more the word-symbols degenerate. It is this continual drifting away of the word-symbols from the natural sounds which are occasioned by emotions that creates the necessity for auxiliary means of expression, and thus gives us instrumental music.

Since the advent of the drum a great stride toward civilization had been made. Mankind no longer lived in caves but built huts and even temples, and the conditions under which he lived must have been similar to those of the natives of Central Africa before travellers opened up the Dark Continent to the caravan of the European trader. If we look up the subject in the narratives of Livingstone or Stanley we find that these people lived in groups of coarsely-thatched huts, the village being almost invariably surrounded by a kind of stockade. Now this manner of living is identically the same as that of all savage tribes which have not passed beyond the drum state of civilization, namely, a few huts huddled together and surrounded by a palisade of bamboo or cane. Since the pith would decompose in a short time, we should probably find that the wind, whirling across such a palisade of pipes—for that is what our bamboos would have turned to—would produce musical sounds, in fact, exactly the sounds that a large set of Pan's pipes would produce. For after all what we call Pan's pipes are simply pieces of bamboo or cane of different lengths tied together and made to sound by blowing across the open tops.

The theory may be objected to on the ground that it scarcely proves the antiquity of the pipe to be less than that of the drum; but the objection is hardly of importance when we consider that the drum was known long before mankind had reached the “hut” stage of civilization. Under the head of pipe, the trumpet and all its derivatives must be accepted. On this point there has been much controversy. But it seems reasonable to believe that once it was found that sound could be produced by blowing across the top of a hollow pipe, the most natural thing to do would be to try the same effect on all hollow things differing in shape and material from the original bamboo. This would account for the conch shells of the Amazons which, according to travellers' tales, were used to proclaim an attack in war; in Africa the tusks of elephants were used; in North America the instrument did not rise above the whistle made from the small bones of a deer or of a turkey's leg.

That the Pan's pipes are the originals of all these species seems hardly open to doubt. Even among the Greeks and Romans we see traces of them in the double trumpet and the double pipe. These trumpets became larger and larger in form, and the force required to play them was such that the player had to adopt a kind of leather harness to strengthen his cheeks. Before this development had been reached, however, I have no doubt that all wind instruments were of the Pan's pipes variety; that is to say, the instruments consisted of a hollow tube shut at one end, the sound being produced by the breath catching on the open edge of the tube.

Direct blowing into the tube doubtless came later. In this case the tube was open at both ends, and the sound was determined by its length and by the force given to the breath in playing. There is good reason for admitting this new instrument to be a descendant of the Pan's pipes, for it was evidently played by the nose at first. This would preclude its being considered as an originally forcible instrument, such as the trumpet.

Now that we have traced the history of the pipe and considered the different types of the instrument, we can see immediately that it brought no great new truth home to man as did the drum.

The savage who first climbed secretly to the top of the stockade around his village to investigate the cause of the mysterious sounds would naturally say that the Great Spirit had revealed a mystery to him; and he would also claim to be a wonder worker. But while his pipe would be accepted to a certain degree, it was nevertheless second in the field and could hardly replace the drum. Besides, mankind had already commenced to think on a higher plane, and the pipe was reduced to filling what gaps it could in the language of the emotions.

The second strongest emotion of the race is love. All over the world, wherever we find the pipe in its softer, earlier form, we find it connected with love songs. In time it degenerated into a synonym for something contemptibly slothful and worthless, so much so that Plato wished to banish it from his “Republic,” saying that the Lydian pipe should not have a place in a decent community.

On the other hand, the trumpet branch of the family developed into something quite different. At the very beginning it was used for war, and as its object was to frighten, it became larger and larger in form, and more formidable in sound. In this respect it only kept pace with the drum, for we read of Assyrian and Thibetan trumpets two or three yards long, and of the Aztec war drum which reached the enormous height of ten feet, and could be heard for miles.

Now this, the trumpet species of pipe, we find also used as an auxiliary “spiritual” help to the drum. We are told by M. Huc, in his “Travels in Thibet,” that the llamas of Thibet have a custom of assembling on the roofs of Lhassa at a stated period and blowing enormous trumpets, making the most hideous midnight din imaginable. The reason given for this was that in former days the city was terrorized by demons who rose from a deep ravine and crept through all the houses, working evil everywhere. After the priests had exorcised them by blowing these trumpets, the town was troubled no more. In Africa the same demonstration of trumpet blowing occurs at an eclipse of the moon; and, to draw the theory out to a thin thread, anyone who has lived in a small German Protestant town will remember the chorals which are so often played before sunrise by a band of trumpets, horns, and trombones from the belfry of some church tower. Almost up to the end of the last century trombones were intimately connected with the church service; and if we look back to Zoroaster we find the sacerdotal character of this species of instrument very plainly indicated.

Now let us turn back to the Pan's pipes and its direct descendants, the flute, the clarinet, and the oboe. We shall find that they had no connection whatever with religious observances. Even in the nineteenth century novel we are familiar with the kind of hero who played the flute—a very sentimental gentleman always in love. If he had played the clarinet he would have been very sorrowful and discouraged; and if it had been the oboe (which, to the best of my knowledge, has never been attempted in fiction) he would have needed to be a very ill man indeed.

Now we never hear of these latter kinds of pipes being considered fit for anything but the dance, love songs, or love charms. In the beginning of the seventeenth century Garcilaso de la Vega, the historian of Peru, tells of the astonishing power of a love song played on a flute. We find so-called “courting” flutes in Formosa and Peru, and Catlin tells of the Winnebago courting flute. The same instrument was known in Java, as the old Dutch settlers have told us. But we never hear of it as creating awe, or as being thought a fit instrument to use with the drum or trumpet in connection with religious rites. Leonardo da Vinci had a flute player make music while he painted his picture of Mona Lisa, thinking that it gave her the expression he wished to catch—that strange smile reproduced in the Louvre painting. The flute member of the pipe species, therefore, was more or less an emblem of eroticism, and, as I have already said, has never been even remotely identified with religious mysticism, with perhaps the one exception of Indra's flute, which, however, never seems to have been able to retain a place among religious symbols. The trumpet, on the other hand, has retained something of a mystical character even to our day. The most powerful illustration of this known to me is in the “Requiem” by Berlioz. The effect of those tremendous trumpet calls from the four corners of the orchestra is an overwhelming one, of crushing power and majesty, much of which is due to the rhythm.

To sum up. We may regard rhythm as the intellectual side of music, melody as its sensuous side. The pipe is the one instrument that seems to affect animals—hooded cobras, lizards, fish, etc. Animals' natures are purely sensuous, therefore the pipe, or to put it more broadly, melody, affects them. To rhythm, on the other hand, they are indifferent; it appeals to the intellect, and therefore only to man.

This theory would certainly account for much of the potency of what we moderns call music. All that aims to be dramatic, tragic, supernatural in our modern music, derives its impressiveness directly from rhythm. 1 What would that shudder of horror in Weber's “Freischütz” be without that throb of the basses? Merely a diminished chord of the seventh. Add the pizzicato in the basses and the chord sinks into something fearsome; one has a sudden choking sensation, as if one were listening in fear, or as if the heart had almost stopped beating. All through Wagner's music dramas this powerful effect is employed, from “The Flying Dutchman” to “Parsifal.” Every composer from Beethoven to Nicodé has used the same means to express the same emotions; it is the medium that pre-historic man first knew; it produced the same sensation of fear in him that it does in us at the present day.

Rhythm denotes a thought; it is the expression of a purpose. There is will behind it; its vital part is intention, power; it is an act. Melody, on the other hand, is an almost unconscious expression of the senses; it translates feeling into sound. It is the natural outlet for sensation. In anger we raise the voice; in sadness we lower it. In talking we give expression to the emotions in sound. In a sentence in which fury alternates with sorrow, we have the limits of the melody of speech. Add to this rhythm, and the very height of expression is reached; for by it the intellect will dominate the sensuous.

1 The strength of the “Fate” motive in Beethoven's fifth symphony undoubtedly lies in the succession of the four notes at equal intervals of time. Beethoven himself marked it So pocht das Schicksal an die Pforte.

Emerson characterized language as “fossil poetry,” but “fossil music” would have described it even better; for as Darwin says, man sang before he became human.

Gerber, in his “Sprache als Kunst,” describing the degeneration of sound symbols, says “the saving point of language is that the original material meanings of words have become forgotten or lost in their acquired ideal meaning.” This applies with special force to the languages of China, Egypt, and India. Up to the last two centuries our written music was held in bondage, was “fossil music,” so to speak. Only certain progressions of sounds were allowed, for religion controlled music. In the Middle Ages folk song was used by the Church, and a certain amount of control was exercised over it; even up to the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries the use of sharps and flats was frowned upon in church music. But gradually music began to break loose from its old chains, and in our own century we see Beethoven snap the last thread of that powerful restraint which had held it so long.

The vital germ of music, as we know it, lay in the fact that it had always found a home in the hearts of the common people of all nations. While from time immemorial theory, mostly in the form of mathematical problems, was being fought over, and while laws were being laid down by religions and governments of all nations as to what music must be and what music was forbidden to be, the vital spark of the divine art was being kept alive deep beneath the ashes of life in the hearts of the oppressed common folk. They still sang as they felt; when the mood was sad the song mirrored the sorrow; if it were gay the song echoed it, despite the disputes of philosophers and the commands of governments and religion. Montaigne, in speaking of language, said with truth, “'Tis folly to attempt to fight custom with theories.” This folk song, to use a Germanism, we can hardly take into account at the present moment, though later we shall see that spark fanned into fire by Beethoven, and carried by Richard Wagner as a flaming torch through the very home of the gods, “Walhalla.”

Let us go back to our dust heap. Words have been called “decayed sentences,” that is to say, every word was once a small sentence complete in itself. This theory seems true enough when we remember that mankind has three languages, each complementing the other. For even now we say many words in one, when that word is reinforced and completed by our vocabulary of sounds and expression, which, in turn, has its shadow, gesture. These shadow languages, which accompany all our words, give to the latter vitality and raise them from mere abstract symbols to living representatives of the idea. Indeed, in certain languages, this auxiliary expression even overshadows the spoken word. For instance, in Chinese, the theng or intonation of words is much more important than the actual words themselves. Thus the third intonation or theng, as it is called in the Pekin dialect, is an upward inflection of the voice. A word with this upward inflection would be unintelligible if given the fourth theng or downward inflection. For instance, the word “kwai” with a downward inflection means “honourable,” but give it an upward inflection “kwai” and it means “devil.”

Just as a word was originally a sentence, so was a tone in music something of a melody. One of the first things that impresses us in studying examples of savage music is the monotonic nature of the melodies; indeed some of the music consists almost entirely of one oft-repeated sound. Those who have heard this music say that the actual effect is not one of a steady repetition of a single tone, but rather that there seems to be an almost imperceptible rising and falling of the voice. The primitive savage is unable to sing a tone clearly and cleanly, the pitch invariably wavering. From this almost imperceptible rising and falling of the voice above and below one tone we are able to gauge more or less the state of civilization of the nation to which the song belongs. This phrase-tone corresponds, therefore, to the sentence-word, and like it, gradually loses its meaning as a phrase and fades into a tone which, in turn, will be used in new phrases as mankind mounts the ladder of civilization.

At last then we have a single tone clearly uttered, and recognizable as a musical tone. We can even make a plausible guess as to what that tone was. Gardiner, in his “Music of Nature,” tells of experiments he made in order to determine the normal pitch of the human voice. By going often to the gallery of the London Stock Exchange he found that the roar of voices invariably amalgamated into one long note, which was always F. If we look over the various examples of monotonic savage music quoted by Fletcher, Fillmore, Baker, Wilkes, Catlin, and others, we find additional corroboration of the statement; song after song, it will be noticed, is composed entirely of F, G, and even F alone or G alone. Such songs are generally ancient ones, and have been crystallized and held intact by religion, in much the same way that the chanting heard in the Roman Catholic service has been preserved.

Let us assume then that the normal tone of the human

voice in speaking is F or G

![]() for men, and for

women the octave higher. This tone does very well

for our everyday life; perhaps a pleasant impression may

raise it somewhat, ennui may depress it slightly; but the

average tone of our “commonplace” talk, if I may call

it that, will be about F. But let some sudden emotion

come, and we find monotone speech abandoned for impassioned

speech, as it has been called. Instead of keeping

the voice evenly on one or two notes, we speak much

higher or lower than our normal pitch.

for men, and for

women the octave higher. This tone does very well

for our everyday life; perhaps a pleasant impression may

raise it somewhat, ennui may depress it slightly; but the

average tone of our “commonplace” talk, if I may call

it that, will be about F. But let some sudden emotion

come, and we find monotone speech abandoned for impassioned

speech, as it has been called. Instead of keeping

the voice evenly on one or two notes, we speak much

higher or lower than our normal pitch.

And these sounds may be measured and classified to a certain extent according to the emotions which cause them, although it must be borne in mind that we are looking at the matter collectively; that is to say, without reckoning on individual idiosyncrasies of expression in speech. Of course we know that joy is apt to make us raise the voice and sadness to lower it. For instance, we have all heard gruesome stories, and have noticed how naturally the voice sinks in the telling. A ghost story told with an upward inflection might easily become humourous, so instinctively do we associate the upward inflection with a non-pessimistic trend of thought. Under stress of emotion we emphasize words strongly, and with this emphasis we almost invariably raise the voice a fifth or depress it a fifth; with yet stronger emotion the interval of change will be an octave. We raise the voice almost to a scream or drop it to a whisper. Strangely enough these primitive notes of music correspond to the first two of those harmonics which are part and parcel of every musical sound. Generally speaking, we may say that the ascending inflection carries something of joy or hope with it, while the downward inflection has something of the sinister and fearful. To be sure, we raise our voices in anger and in pain, but even then the inflection is almost always downward; in other words, we pitch our voices higher and let them fall slightly. For instance, if we heard a person cry “Ah/” we might doubt its being a cry of pain, but if it were “Ah\” we should at once know that it was caused by pain, either mental or physical.

The declamation at the end of Schubert's “Erlking” would have been absolutely false if the penultimate note had ascended to the tonic instead of descending a fifth. “The child lay dead.”

How fatally hopeless would be the opening measures of “Tristan and Isolde” without that upward inflection which comes like a sunbeam through a rift in the cloud; with a downward inflection the effect would be that of unrelieved gloom. In the Prelude to “Lohengrin,” Wagner pictures his angels in dazzling white. He uses the highest vibrating sounds at his command. But for the dwarfs who live in the gloom of Niebelheim he chooses deep shades of red, the lowest vibrating colour of the solar spectrum. For it is in the nature of the spiritual part of mankind to shrink from the earth, to aspire to something higher; a bird soaring in the blue above us has something of the ethereal; we give wings to our angels. On the other hand, a serpent impresses us as something sinister. Trees, with their strange fight against all the laws of gravity, striving upward unceasingly, bring us something of hope and faith; the sight of them cheers us. A land without trees is depressing and gloomy. As Ruskin says, “The sea wave, with all its beneficence, is yet devouring and terrible; but the silent wave of the blue mountain is lifted towards Heaven in a stillness of perpetual mercy; and while the one surges unfathomable in its darkness, the other is unshaken in its faithfulness.”

And yet so strange is human nature that that which we call civilization strives unceasingly to nullify emotion. The almost childlike faith which made our church spires point heavenward also gave us Gothic architecture, that emblem of frail humanity striving towards the ideal. It is a long leap from that childlike faith to the present day of skyscrapers. For so is the world constituted. A great truth too often becomes gradually a truism, then a merely tolerated and uninteresting theory; gradually it becomes obsolete and sometimes even degenerates into a symbol of sarcasm or a servant of utilitarianism. This we are illustrating every day of our lives. We speak of a person's being “silly,” and yet the word comes from “sælig,” old English for “blessed”; to act “sheepishly” once had reference to divine resignation, “even as a sheep led to the slaughter,” and so on ad infinitum. We build but few great cathedrals now. Our tall buildings generally point to utilitarianism and the almighty dollar.

But in the new art, music, we have found a new domain in which impulses have retained their freshness and warmth, in which, to quote Goethe, “first comes the act, then the word”; first the expression of emotion, then the theory that classifies it; a domain in which words cannot lose their original meanings entirely, as in speech. For in spite of the strange twistings of ultra modern music, a simple melody still embodies the same pathos for us that it did for our grandparents. To be sure the poignancy of harmony in our day has been heightened to an incredible degree. We deal in gorgeous colouring and mighty sound masses which would have been amazing in the last century; but still through it all we find in Händel, Beethoven, and Schubert, up to Wagner, the same great truths of declamation that I have tried to explain to you.

Herbert Spencer, in an essay on “The Origin and Functions of Music,” speaks of speech as the parent of music. He says, “utterance, which when languaged is speech, gave rise to music.” The definition is incomplete, for “languaged utterance,” as he calls it, which is speech, is a duality, is either an expression of emotion or a mere symbol of emotion, and as such has gradually sunk to the level of the commonplace. As Rowbotham points out, impassioned speech is the parent of music, while unimpassioned speech has remained the vehicle for the smaller emotions of life, the everyday expression of everyday emotions.

In studying the music of different nations we are confronted by one fact which seems to be part and parcel of almost every nationality, namely, the constant recurrence of what is called the five tone (pentatonic) scale. We find it in primitive forms of music all the world over, in China and in Scotland, among the Burmese, and again in North America. Why it is so seems almost doomed to remain a mystery. The following theory may nevertheless be advanced as being at least plausible:

Vocal music, as we understand it, and as I have already explained, began when the first tone could be given clearly; that is to say, when the sound sentence had amalgamated into the single musical tone. The pitch being sometimes F, sometimes G, sudden emotion gives us the fifth, C or D, and the strongest emotion the octave, F or G. Thus we have already the following sounds in our first musical scale.

We know how singers slur from one tone to another. It is a fault that caused the fathers of harmony to prohibit what are called hidden fifths in vocal music. The jump from G to C in the above scale fragment would be slurred, for we must remember that the intoning of clear individual sounds was still a novelty to the savage. Now the distance from G to C is too small to admit two tones such as the savage knew; consequently, for the sake of uniformity, he would try to put but one tone between, singing a mixture of A and B♭, which sound in time fell definitely to A, leaving the mystery of the half-tone unsolved. This addition of the third would thus fall in with the law of harmonics again. First we have the keynote; next in importance comes the fifth; and last of all the third. Thus again is the absence of the major seventh in our primitive scale perfectly logical; we may search in vain in our list of harmonics for the tone which forms that interval.

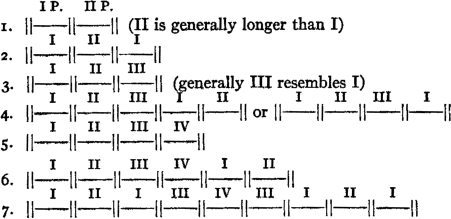

Now that we have traced the influence of passionate utterance on music, it still remains for us to consider the influence of something very different. The dance played an important rôle in the shaping of the art of music; for to it music owes periodicity, form, the shaping of phrases into measures, even its rests. And in this music is not the only debtor, for poetry owes its very “feet” to the dance.

Now the dance was, and is, an irresponsible thing.

It had no raison d'être except purely physical enjoyment.

This rhythmic swaying of the body and light tapping of

the feet have always had a mysterious attraction and

fascination for mankind, and music and poetry were

caught in its swaying measures early in the dawn of art.

When a man walks, he takes either long steps or short

steps, he walks fast or slow. But when he takes one

long step and one short one, when one step is slow and the

other fast, he no longer walks, he dances. Thus we may

say with reasonable certainty that triple time arose directly

from the dance, for triple time is simply one strong, long

beat followed by a short, light one, viz.:

![]() or

or

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() ,

the “trochee” in our poetry.

,

the “trochee” in our poetry.

![]() ,

Iambic.

The spondee

,

Iambic.

The spondee

![]() or

or

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() ,

which is the rhythm of

prose, we already possessed; for when we walk it is in

spondees, namely, in groups of two equal steps. Now

imagine dancing to spondees! At first the steps will be

equal, but the body rests on the first beat; little by little

the second beat, being thus relegated to a position of

relative unimportance, becomes shorter and shorter, and

we rest longer on the first beat. The result is the trochaic

rhythm. We can see that this result is inevitable, even

if only the question of physical fatigue is considered. And,

to carry on our theory, this very question of fatigue still

further develops rhythm. The strong beat always coming

on one foot, and the light beat on the other, would soon

tire the dancer; therefore some way must be found to

make the strong beat alternate from one foot to the other.

The simplest, and in fact almost the only way to do this,

is to insert an additional short beat before the light beat.

This gives us

,

which is the rhythm of

prose, we already possessed; for when we walk it is in

spondees, namely, in groups of two equal steps. Now

imagine dancing to spondees! At first the steps will be

equal, but the body rests on the first beat; little by little

the second beat, being thus relegated to a position of

relative unimportance, becomes shorter and shorter, and

we rest longer on the first beat. The result is the trochaic

rhythm. We can see that this result is inevitable, even

if only the question of physical fatigue is considered. And,

to carry on our theory, this very question of fatigue still

further develops rhythm. The strong beat always coming

on one foot, and the light beat on the other, would soon

tire the dancer; therefore some way must be found to

make the strong beat alternate from one foot to the other.

The simplest, and in fact almost the only way to do this,

is to insert an additional short beat before the light beat.

This gives us

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() or

or

![]() ,

the dactyl in poetry.

,

the dactyl in poetry.

We have, moreover, here discovered the beginning of

form, and have begun to group our musical tones in

measures and phrases; for our second dactyl is slightly

different from the first, because the right foot begins the

first and the left foot the second. We have two measures

![]() and one phrase, for after the second

measure the right foot will again have the beat and will

begin another phrase of two measures.

and one phrase, for after the second

measure the right foot will again have the beat and will

begin another phrase of two measures.

Carry this theory still further, and we shall make new discoveries. If we dance in the open air, unless we would dance over the horizon, we must turn somewhere; and if we have but a small space in which to dance, the turns must come sooner and oftener. Even if we danced in a circle we should need to reverse the motion occasionally, in order to avoid giddiness; and this would measure off our phrases into periods and sections.

Thus we see music dividing into two classes, one purely emotional, the other sensuous; the one arising from the language of heroes, the other from the swaying of the body and the patter of feet. To both of these elements, if we may call them so, metre and melody brought their power; to declamation, metre brought its potent vitality; to the dance, melody added its soft charm and lulling rhyme. The intellectual in music, namely, rhythm and declamation, thus joined forces, as did the purely sensuous elements, melody and metre (dance). At the first glance it would seem as if the dance with its rhythms contradicted the theory of rhythm as being one of the two vital factors in music; but when we consider the fact that dance-rhythms are merely regular pulsations (once commenced they pulsate regularly to the end, without break or change), and when we consider that just this unbroken regularity is the very antithesis of what we mean by rhythm, the purely sensuous nature of the dance is manifest. Strauss was the first to recognize this defect in the waltz, and he remedied it, so far as it lay within human skill, by a marvellous use of counter-rhythms, thus infusing into the dance a simulation of intellectuality.

The weaving together of these elements into one art-fabric has been the ideal of all poets from Homer to Wagner. The Greeks idealized their dances; that is to say, they made their dances fit their declamation. In the last two centuries, and especially in the middle of the nineteenth, we have danced our highest flights of impassioned speech. For what is the symphony, sonata, etc., but a remnant of the dance form? The choric dances of Stesichorus and Pindar came strangely near our modern forms, but it was because the form fitted the poem. In our modern days, we too often, Procrustes-like, make our ideas to fit the forms. We put our guest, the poetic thought, that comes to us like a homing bird from out the mystery of the blue sky—we put this confiding stranger straightway into that iron bed, the “sonata form,” or perhaps even the third rondo form, for we have quite an assortment. Should the idea survive and grow too large for the bed, and if we have learned to love it too much to cut off its feet and thus make it fit (as did that old robber of Attica), why we run the risk of having some critic wise in his theoretical knowledge, say, as was and is said of Chopin, “He is weak in sonata form!”

There are two ways of looking at music: first, as impassioned speech, the nearest psychologically-complete utterance of emotion known to man; second, as the dance, comprising as it does all that appeals to our nature. And there is much that is lovely in this idea of nature—for do not the seasons dance, and is it not in that ancient measure we have already spoken of, the trochaic? Long Winter comes with heavy foot, and Spring is the light-footed. Again, Summer is long, and Autumn short and cheery; and so our phrase begins again and again. We all know with what periodicity everything in nature dances, and how the smallest flower is a marvel of recurring rhymes and rhythms, with perfume for a melody. How Shakespeare's Beatrice charms us when she says, “There a star danced, and under that was I born.”

And yet man is not part of Nature. Even in the depths of the primeval forest, that poor savage, whom we found listening fearfully to the sound of his drum, knew better. Mankind lives in isolation, and Nature is a thing for him to conquer. For Nature is a thing that exists, while man thinks. Nature is that which passively lives while man actively wills. It is the strain of Nature in man that gave him the dance, and it is his godlike fight against Nature that gave him impassioned speech; beauty of form and motion on one side, all that is divine in man on the other; on one side materialism, on the other idealism.

We have traced the origin of the drum, pipe, and the voice in music. It still remains for us to speak of the lyre and the lute, the ancestors of our modern stringed instruments. The relative antiquity of the lyre and the lute as compared with the harp has been much discussed, the main contention against the lyre being that it is a more artificial instrument than the harp; the harp was played with the fingers alone, while the lyre was played with a plectrum (a small piece of metal, wood, or ivory). Perhaps it would be safer to take the lute as the earliest form of the stringed instrument, for, from the very first, we find two species of instruments with strings, one played with the fingers, the prototype of our modern harps, banjos, guitars, etc., the other played with the plectrum, the ancestor of all our modern stringed instruments played by means of bows and hammers, such as violins, pianos, etc.

However this may be, one thing is certain, the possession of these instruments implies already a considerable measure of culture, for they were not haphazard things. They were made for a purpose, were invented to fill a gap in the ever-increasing needs of expression. In Homer we find a description of the making of a lyre by Hermes, how this making of a lyre from the shell of a tortoise that happened to pass before the entrance to the grotto of his mother, Maïa, was his first exploit; and that he made it to accompany his song in praise of his father Zeus. We must accept this explanation of the origin of the lyre, namely, that it was deliberately invented to accompany the voice. For the lyre in its primitive state was never a solo instrument; the tone was weak and its powers of expression were exceedingly limited. On the other hand, it furnished an excellent background for the voice and, which was still more to the point, the singer could accompany himself. The drum had too vague a pitch, and the flute or pipe necessitated another performer, besides having too much similarity of tone to the voice to give sufficient contrast. Granted then that the lyre was invented to accompany the voice, and without wasting time with surmises as to whether the first idea of stringed instruments was received from the twanging of a bowstring or the finding of a tortoise shell with the half-dessicated tendons of the animal still stretching across it, let us find when the instrument was seemingly first used.

That the lyre and lute are of Asiatic origin is generally conceded, and even in comparatively modern times, Asia seems to be the home of its descendants. The Tartars have been called the troubadours of Asia—and of Asia in the widest sense of the word—penetrating into the heart of the Caucasus on the west and reaching through the country eastward to the shores of the Yellow Sea. Marco Polo, the celebrated Venetian traveller, and M. Huc, a French missionary to China and Thibet, as well as Spencer, Atkinson, and many others, speak of the wandering bards of Asia. Marco Polo's account of how Jenghiz Kahn, the great Mongol conqueror, sent an expedition composed entirely of minstrels against Mien, a city of 30,000 inhabitants, has often been quoted to show what an abundance—or perhaps superfluity would be the better word—of musicians he had at his court.

That the lyre could not be of Greek origin is proved by the fact that no root has been discovered in the language for lyra, although there are many special names for varieties of the instrument. Leaving aside the question of the geographical origin of the instrument, we may say, broadly, that wherever we find a nation with even the smallest approach to a history, there we shall find bards singing of the exploits of heroes, and always to the accompaniment of the lyre or the lute. For at last, by means of these instruments, impassioned speech was able to lift itself permanently above the level of everyday life, and its lofty song could dispense with the soft, sensuous lull of the flute. And we shall see later how these bards became seers, and how even our very angels received harps, so closely did the instrument become associated with what I have called impassioned speech, which, in other words, is the highest expression of what we consider godlike in man.

The music of the Hebrews presents one of the most interesting subjects in musical history, although it has an unfortunate defect in common with so many kindred subjects, namely, that the most learned dissertation must invariably end with a question mark. When we read in Josephus that Solomon had 200,000 singers, 40,000 harpers, 40,000 sistrum players, and 200,000 trumpeters, we simply do not believe it. Then too there is lack of unanimity in the matter of the essential facts. One authority, describing the machol, says it is a stringed instrument resembling a modern viola; another describes it as a wind instrument somewhat like a bagpipe; still another says it is a metal ring with a bell attachment like an Egyptian sistrum; and finally an equally respected authority claims that the machol was not an instrument at all, but a dance. Similarly the maanim has been described as a trumpet, a kind of rattle box with metal clappers, and we even have a full account in which it figures as a violin.

The temple songs which we know have evidently been much changed by surrounding influences, just as in modern synagogues the architecture has not held fast to ancient Hebrew models but has been greatly influenced by different countries and peoples. David may be considered the founder of Hebrew music, and his reign has been well called an “idyllic episode in the otherwise rather grim history of Israel.”

Of the instruments named in the Scriptures, that called the harp in our English translation was probably the kinnor, a kind of lyre played by means of a plectrum, which was a small piece of metal, wood, or bone. The psaltery or nebel (which was of course derived from the Egyptian nabla, just as the kinnor probably was in some mysterious manner derived from the Chinese kin) was a kind of dulcimer or zither, an oblong box with strings which were struck by small hammers. The timbrel corresponds to our modern tambourine. The schofar and keren were horns. The former was the well-known ram's horn which is still blown on the occasion of the Jewish New Year.

In the Talmud mention is made of an organ consisting of ten pipes which could give one hundred different sounds, each pipe being able to produce ten tones. This mysterious instrument was called magrepha, and although but one Levite (the Levites were the professional musicians among the Hebrews) was required to play it, and although it was only about three feet in length, its sound was so tremendous that it could be heard ten miles away. Hieronymus speaks of having heard it on the Mount of Olives when it was played in the Temple at Jerusalem. To add to the mystery surrounding this instrument, it has been proved by several learned authorities that it was merely a large drum; and, to cap the climax, other equally respected writers have declared that this instrument was simply a large shovel which, after being used for the sacrificial fire in the temple, was thrown to the ground with a great noise, to inform the people that the sacrifice was consummated.

It is reasonably certain that the seemingly incongruous titles to the Psalms were merely given to denote the tune to which they were to be sung, just as in our modern hymns we use the words Canterbury, Old Hundredth, China, etc.

The word selah has never been satisfactorily explained, some readings giving as its meaning “forever,” “hallelujah,” etc., while others say that it means repeat, an inflection of the voice, a modulation to another key, an instrumental interlude, a rest, and so on without end.

Of one thing we may be certain regarding the ancient Hebrews, namely, that their religion brought something into the world that can never again be lost. It fostered idealism, and gave mankind something pure and noble to live for, a religion over which Christianity shed the sunshine of divine mercy and hope. That the change which was to be wrought in life was sharply defined may be seen by comparing the great songs of the different nations. For up to that time a song of praise meant praise of a King. He was the sun that warmed men's hearts, the being from whom all wisdom came, and to whom men looked for mercy. If we compare the Egyptian hymns with those of the Hebrews, the difference is very striking. On the walls of the great temples of Luxor and the Ramesseum at Thebes, as well as on the wall of the temple of Abydos and in the main hall of the great rock-hewn temple of Abu-Simbel, in Nubia, is carved the “Epic of Pentaur,” the royal Egyptian scribe of Rameses II:

My king, his arms are mighty, his heart is firm. He bends his bow and none can resist him. Mightier than a hundred thousand men he marches forward. His counsel is wise and when he wears the royal crown, Alef, and declares his will, he is the protector of his people. His heart is like a mountain of iron. Such is King Rameses.

If we turn to the Hebrew prophets, this is their song:

The mountains melted from before the Lord and before Him went the pestilence; burning coals went forth at His feet. Hell is naked before Him and destruction hath no covering. He hangeth the earth upon nothing and the pillars of heaven tremble and are astonished at His reproof. Though He slay me, yet will I trust in Him. For I know that my Redeemer liveth, and at the last day He shall stand upon the earth.

As with the Hebrews, music among the Hindus was closely bound to religion. When, 3000 years before the Christian era, that wonderful, tall, white Aryan race of men descended upon India from the north, its poets already sang of the gods, and the Aryan gods were of a different order from those known to that part of the world; for they were beautiful in shape, and friendly to man, in great contrast to the gods of the Davidians, the pre-Aryan race and stock of the Deccan. These songs formed the Rig-Veda, and are the nucleus from which all Hindu religion and art emanate.

We already know that when the auxiliary speech which we call music was first discovered, or, to use the language of all primitive nations, when it was first bestowed on man by the gods, it retained much of the supernatural potency that its origin would suggest. In India, music was invested with divine power, and certain hymns—especially the prayer or chant of Vashishtha—were, according to the Rig-Veda, all powerful in battle. Such a magic song, or chant, was called a brahma, and he who sang it a brahmin. Thus the very foundation of Brahminism, from which rose Buddhism in the sixth century B.C., can be traced back to the music of the sacred songs of the Rig-Veda of India. The priestly or Brahmin caste grew therefore from the singers of the Vedic hymns. The Brahmins were not merely the keepers of the sacred books, or Vedas, the philosophy, science, and laws of the ancient Hindus (for that is how the power of the caste developed), but they were also the creators and custodians of its secular literature and art. Two and a half thousand years later Prince Gautama or Buddha died, after a life of self-sacrifice and sanctity. On his death five hundred of his disciples met in a cave near Rajagriha to gather together his sayings, and chanted the lessons of their great master. These songs became the bible of Buddhism, just as the Vedas are the bible of Brahminism, for the Hindu word for a Buddhist council means literally “a singing together.”

Besides the sacred songs of the Brahmins and Buddhists, the Hindus had many others, some of which partook of the occult powers of the hymns, occult powers that were as strongly marked as those of Hebrew music. For while the latter are revealed in the playing of David before Saul, in the influence of music on prophecy, the falling of the walls of Jericho at the sound of the trumpets of Joshua, etc., in India the same supernatural power was ascribed to certain songs. For instance, there were songs that could be sung only by the gods, and one of them, so the legend runs, if sung by a mortal, would envelop the singer in flames. The last instance of the singing of this song was during the reign of Akbar, the great Mogul emperor (about 1575 A.D.). At his command the singer sang it standing up to his neck in the river Djaumna, which, however, did not save him, for, according to the account, the water around him boiled, and he was finally consumed by a flame of fire. Another of Akbar's singers caused the palace to be wrapped in darkness by means of one of these magic songs, and another averted a famine by causing rain to fall when the country was threatened by drought. Animals were also tamed by means of certain songs, the only relic of which is found in the serpent charmers' melodies, which, played on a kind of pipe, seem to possess the power of controlling cobras and the other snakes exhibited by the Indian fakirs.

Many years before Gautama's time, the brahmas or singers of sacred songs of ancient India formed themselves into a caste or priesthood; and the word “Brahma,” from meaning a sacred singer, became the name of the supreme deity; in time, as the nation grew, other gods were taken into the religion. Thus we find in pre-Buddha times the trinity of gods: Brahma, Vishnu, and Siva, with their wives, Sarasvati or learning, Lakshmi or beauty, and Paravati, who was also called Kali, Durga, and Mahadevi, and was practically the goddess of evil. Of these gods Brahma's consort, Sarasvati, the goddess of speech and learning, brought to earth the art of music, and gave to mankind the Vina.

This instrument is still in use and may be called the

national instrument of India. It is composed of a cylindrical

pipe, often bamboo, about three and a half feet

long, at each end of which is fixed a hollow gourd to

increase the tone. It is strung lengthwise with seven

metal wires held up by nineteen wooden bridges, just as

the violin strings are supported by a bridge. The scale of

the instrument proceeds in half tones from

![]()

The tones are produced by plucking the strings with the

fingers (which are covered with a kind of metal thimble),

and the instrument is held so that one of the gourds hangs

over the left shoulder, just as one would hold a very long-necked

banjo.

It is to the Krishna incarnation of Vishnu that the Hindu scale is ascribed. According to the legend, Krishna or Vishnu came to earth and took the form of a shepherd, and the nymphs sang to him in many thousand different keys, of which from twenty-four to thirty-six are known and form the basis of Hindu music. To be sure these keys, being formed by different successions of quarter-tones, are practically inexhaustible, and the 16,000 keys of Krishna are quite practicable. The differences in tone, however, were so very slight that only a few, of them have been retained to the present time.

The Hindus get their flute from the god Indra, who, from being originally the all-powerful deity, was relegated by Brahminism to the chief place among the minor gods—from being the god of light and air he came to be the god of music. His retinue consisted of the gandharvas, and apsaras, or celestial musicians and nymphs, who sang magic songs. After the rise and downfall of Buddhism in India the term raga degenerated to a name for a merely improvised chant to which no occult power was ascribed.

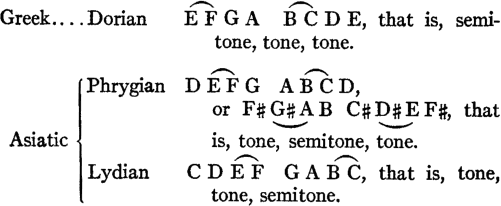

The principal characteristics in modern Hindu music are a seemingly instinctive sense of harmony; and although the actual chords are absent, the melodic formation of the songs plainly indicates a feeling for modern harmony, and even form. The actual scale resembles our European scale of twelve semitones (twenty-two s'rutis, quarter-tones), but the modal development of these sounds has been extraordinary. Now a “mode” is the manner in which the notes of a scale are arranged. For instance, in our major mode the scale is arranged as follows: tone, tone, semitone, tone, tone, tone, semitone. In India there are at present seventy-two modes in use which are produced by making seventy-two different arrangements of the scale by means of sharps and flats, the only rule being that each degree of the scale must be represented; for instance, one of the modes Dehrásan-Karabhárna corresponds to our major scale. Our minor (harmonic) scale figures as Kyravâni. Tânarupi corresponds to the following succession of notes,

It can thus easily be seen how the seventy-two modes are possible and practicable. Observe that the seven degrees of the scale are all represented in these modes, the difference between them being in the placing of half-tones by means of sharps or flats. Not content with the complexity that this modal system brought into their music, the Hindus have increased it still more by inventing a number of formulæ called ragas (not to be confounded with those rhapsodical songs, the modern descendant of the magic chants, previously mentioned).

In making a Hindu melody (which of course must be in one of the seventy-two modes, just as in English we should say that a melody must be in one of our two modes, either major or minor) one would have to conform to one of the ragas, that is to say, the melodic outline would have to conform to certain rules, both in ascending and descending. These rules consist of omitting notes of the modes, in one manner when the melody ascends, and in another when it descends. Thus, in the raga called Mohànna, in ascending the notes must be arranged in the following order: 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 8; in descending it is 8, 7, 5, 4, 2, 1. Thus if we wished to write a melody in the mode Tânarupi—raga Mohànna—we could never use the fourth, F, or the seventh, B, if our melody ascended; if our melody descended we should have to avoid the sixth, A♯, and the third, E♭♭. As one can easily perceive, many strange melodic effects are produced by these means. For instance, in the raga Mohànna, in which the fourth and seventh degrees of the scale are avoided in ascending, if it were employed in the mode Dehrásin-Karabhárna, which corresponds to our own major scale, it would have a pronounced Scotch tinge so long as the melody ascended; but let it descend and the Scotch element is deserted for a decided North American Indian, notably Sioux tinge. The Hindus are an imaginative race, and invest all these ragas and modes with mysterious attributes, such as anger, love, fear, and so on. They were even personified as supernatural beings; each had his or her special name and history. It was proper to use some of them only at midday, some in the morning, and some at night. If the mode or raga is changed during a piece, it is expressed in words, by saying, for instance, that “Mohànna” (the new “raga”) is here introduced to the family of Tânarupi. The melodies formed from these modes and ragas are divided into four classes, Rektah, Teranah, Tuppah, and Ragni. The Rektah is in character light and flowing. It falls naturally into regular periods, and resembles the Teranah, with the exception that the latter is only sung by men. The character of the Tuppah is not very clear, but the Ragni is a direct descendant of the old magic songs and incantations; in character it is rhapsodical and spasmodic.

In speaking of the music of antiquity we are seriously hampered by the fact that there is practically no actual music in existence which dates back farther than the eighth or tenth century of the present era. Even those well-known specimens of Greek music, as they are claimed to be, the hymns to Apollo, Nemesis, and Calliope, do not date farther back than the third or fourth century, and even these are by no means generally considered authentic. Therefore, so far as actual sounds go, all music of which we have any practical knowledge dates from about the twelfth century.

Theoretically, we have the most minute knowledge of the scientific aspect of music, dating from more than five hundred years before the Christian era. This knowledge, however, is worse than valueless, for it is misleading. For instance, it would be a very difficult thing for posterity to form any idea as to what our music was like if all the actual music in the world at the present time were destroyed, and only certain scientific works such as that of Helmholtz on acoustics and a few theoretical treatises on harmony, form, counterpoint and fugue were saved.

From Helmholtz's analysis of sounds one would get the idea that the so-called tempered scale of our pianos caused thirds and sixths to sound discordantly.

From the books on harmony one would gather that consecutive fifths and octaves and a number of other things were never indulged in by composers, and to cap the climax one would naturally accept the harmony exercises contained in the books as being the very acme of what we loved best in music. Thus we see that any investigation into the music of antiquity must be more or less conjectural.

Let us begin with the music of the Egyptians. The oldest existing musical instrument of which we have any knowledge is an Egyptian lyre to be found in the Berlin Royal Museum. It is about four thousand years old, dating from the period just before the expulsion of the Hyksos or “Shepherd” kings.

At that time (the beginning of the eighteenth dynasty, 1500–2000 B.C.) Egypt was just recovering from her five hundred years of bondage, and music must already have reached a wonderful state of development. In wall paintings of the eighteenth dynasty we see flutes, double flutes, and harps of all sizes, from the small one carried in the hand, to the great harps, almost seven feet high, with twenty-one strings; the never-failing sistrum (a kind of rattle); kitharas, the ancestors of our modern guitars; lutes and lyres, the very first in the line of instruments culminating in the modern piano.

One hesitates to class the trumpets of the Egyptians in the same category, for they were war instruments, the tone of which was probably always forced, for Herodotus says that they sounded like the braying of a donkey. The fact that the cheeks of the trumpeter were reinforced with leather straps would further indicate that the instruments were used only for loud signalling.

According to the mural paintings and sculptures in the tombs of the Egyptians, all these instruments were played together, and accompanied the voice. It has long been maintained that harmony was unknown to the ancients because of the mathematical measurement of sounds. This might be plausible for strings, but pipes could be cut to any size. The positions of the hands of the executants on the harps and lyres, as well as the use of short and long pipes, make it appear probable that something of what we call harmony was known to the Egyptians.

We must also consider that their paintings and sculptures were eminently symbolic. When one carves an explanation in hard granite it is apt to be done in shorthand, as it were. Thus, a tree meant a forest, a prisoner meant a whole army; therefore, two sculptured harpists or flute players may stand for twenty or two hundred. Athenæus, who lived at the end of the second and beginning of the third century, A.D., speaks of orchestras of six hundred in Ptolemy Philadelphus's time (300 B.C.), and says that three hundred of the players were harpers, in which number he probably includes players on other stringed instruments, such as lutes and lyres. It is therefore to be inferred that the other three hundred played wind and percussion instruments. This is an additional reason for conjecturing that they used chords in their music; for six hundred players, not to count the singers, would hardly play entirely in unison or in octaves. The very nature of the harp is chordal, and the sculptures always depict the performer playing with both hands, the fingers being more or less outstretched. That the music must have been of a deep, sonorous character, we may gather from the great size of the harps and the thickness of their strings. As for the flutes, they also are pictured as being very long; therefore they must have been low in pitch. The reed pipes, judging from the pictures and sculptures, were no higher in pitch than our oboes, of which the highest note is D and E above the treble staff.

It is claimed that so far as the harps were concerned, the music must have been strictly diatonic in character. To quote Rowbotham, “the harp, which was the foundation of the Egyptian orchestra, is an essentially non-chromatic instrument, and could therefore only play a straight up and down diatonic scale.” Continuing he says, “It is plain therefore that the Egyptian harmony was purely diatonic; such a thing as modern modulation was unknown, and every piece from beginning to end was played in the same key.” That this position is utterly untenable is very evident, for there was nothing to prevent the Egyptians from tuning their harps in the same order of tones and half tones as is used for our modern pianos. That this is even probable may be assumed from the scale of a flute dating back to the eighteenth or nineteenth century B.C. (1700 or 1600 B.C.), which was found in the royal tombs at Thebes, and which is now in the Florence Museum.

The only thing about which we may be reasonably certain in regard to Egyptian music is that, like Egyptian architecture, it must have been very massive, on account of the preponderance in the orchestra of the low tones of the stringed instruments.

The sistrum was, properly speaking, not considered a musical instrument at all. It was used only in religious ceremonies, and may be considered as the ancestor of the bell that is rung at the elevation of the Host in Roman Catholic churches. Herodotus (born 485 B.C.) tells us much about Egyptian music, how the great festival at Bubastis in honour of the Egyptian Diana (Bast or Pascht), to whom the cat was sacred, was attended yearly by 700,000 people who came by water, the boats resounding with the clatter of castanets, the clapping of hands, and the soft tones of thousands of flutes. Again he tells us of music played during banquets, and speaks of a mournful song called Maneros. This, the oldest song of the Egyptians (dating back to the first dynasty), was symbolical of the passing away of life, and was sung in connection with that gruesome custom of bringing in, towards the end of a banquet, an effigy of a corpse to remind the guests that death is the birthright of all mankind, a custom which was adopted later by the Romans.

Herodotus also gives us a vague but very suggestive glimpse of what may have been the genesis of Greek tragedy, for he was permitted to see a kind of nocturnal Egyptian passion play, in which evidently the tragedy of Osiris was enacted with ghastly realism. Osiris, who represents the light, is hunted by Set or Typhon, the god of darkness, and finally torn to pieces by the followers of Set, and buried beneath the waters of the lake; Horus, the son of Osiris, avenges his death by subduing Set, and Osiris appears again as the ruler of the shadowland of death.