The Project Gutenberg EBook of Ginseng and Other Medicinal Plants, by

A. R. (Arthur Robert) Harding

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Ginseng and Other Medicinal Plants

A Book of Valuable Information for Growers as Well as

Collectors of Medicinal Roots, Barks, Leaves, Etc.

Author: A. R. (Arthur Robert) Harding

Release Date: December 5, 2010 [EBook #34570]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK GINSENG AND OTHER MEDICINAL PLANTS ***

Produced by Linda M. Everhart, Blairstown, Missouri (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

When the price of Ginseng advanced some years ago hundreds engaged in the business who knew little or nothing of farming, plant raising and horticulture. That they largely failed is not to be wondered at. Later many began in a small way and succeeded. Many of these were farmers and gardeners. Others were men who had hunted, trapped and gathered "seng" from boyhood. They therefore knew something of the peculiarities of Ginseng.

It is from the experience of these men that this work is largely made up — writings of those who are in the business.

Golden seal is also attracting considerable attention owing to the rapid increase in price during the early years of the present century. The growing of this plant is given careful attention also.

Many other plants are destined to soon become valuable. A work gotten out by the government — American root drugs — contains a great deal of value in regard habits, range, description, common names, price, uses, etc., etc., so that some of the information contained in this book is taken therefrom. The prices named in the government bulletin which was issued in 1907 were those prevailing at that time — they will vary, in the future, largely according to the supply and demand.

The greatest revenue derived from plants for medicinal purposes is derived from the roots, yet there are certain ones where the leaves and bark are used. Therefore to be complete some space is given to these plants. The digging of the roots, of course, destroys the plant as well as does the peeling of the bark, while leaves secured is clear gain — in other words, if gathered when matured the plant or shrub is not injured and will produce leaves each year.

The amount of root drugs used for medicinal purposes will increase as the medical profession is using of them more and more. Again the number of people in the world is rapidly increasing while the forests (the natural home of root drugs) are becoming less each year. This shows that growers of medicinal roots will find a larger market in the future than in the past.

Those who know something of medicinal plants — "Root Drugs" — can safely embark in their cultivation, for while prices may ease off — go lower — at times, it is reasonably certain that the general trend will be upward as the supply growing wild is rapidly becoming less each year.

A. R. Harding.

With the single exception of ginseng, the hundred of plants whose roots are used for medical purposes, America is the main market and user. Ginseng is used mainly by the Chinese. The thickly inhabited Chinese Empire is where the American ginseng is principally used. To what uses it is put may be briefly stated, as a superstitious beverage. The roots with certain shapes are carried about the person for charms. The roots resembling the human form being the most valuable.

The most valuable drugs which grow in America are ginseng and golden seal, but there are hundreds of others as well whose leaves, barks, seeds, flowers, etc., have a market value and which could be cultivated or gathered with profit. In this connection an article which appeared in the Hunter-Trader-Trapper, Columbus, Ohio, under the title which heads this chapter is given in full:

To many unacquainted with the nature of the various wild plants which surround them in farm and out-o'-door life, it will be a revelation to learn that the world's supply of crude, botanical (vegetable) drugs are to a large extent gotten from this class of material. There are more than one thousand different kinds in use which are indigenous or naturalized in the United States. Some of these are very valuable and have, since their medicinal properties were discovered, come into use in all parts of the world; others now collected in this country have been brought here and, much like the English sparrow, become in their propagation a nuisance and pest wherever found.

The impression prevails among many that the work of collecting the proper kind, curing and preparing for the market is an occupation to be undertaken only by those having experience and a wide knowledge of their species, uses, etc. It is a fact, though, that everyone, however little he may know of the medicinal value of such things, may easily become familiar enough with this business to successfully collect and prepare for the market many different kinds from the start.

There are very large firms throughout the country whose sole business is for this line of merchandise, and who are at all times anxious to make contracts with parties in the country who will give the work business-like attention, such as would attend the production of other farm articles, and which is so necessary to the success of the work.

If one could visit the buyers of such firms and ask how reliable they have found their sources of supply for the various kinds required, it would provoke much laughter. It is quite true that not more than one in one hundred who write these firms to get an order for some one or more kinds they might supply, ever give it sufficient attention to enable a first shipment to be made. Repeated experiences of this kind have made the average buyer very promptly commit to the nearest waste basket all letters received from those who have not been doing this work in the past, recognizing the utter waste of time in corresponding with those who so far have shown no interest in the work.

The time is ripe for those who are willing to take up this work, seriously giving some time and brains to solving the comparatively easy problems of doing this work at a small cost of time and money and successfully compete for this business, which in many cases is forced to draw supplies from Europe, South America, Africa, and all parts of the world.

From the writer's observation, more of these goods are not collected in this country on account of the false ideas those investigating it have of the amount of money to be made from the work, than from any other reason; they are led to believe that untold wealth lies easily within their reach, requiring only a small effort on their part to obtain it. Many cases may be cited of ones who have laboriously collected, possibly 50 to 100 pounds of an article, and when it was discovered that from one to two dollars per pound was not immediately forthcoming, pronounced the dealer a thief and never again considered the work.

In these days when all crude materials are being bought, manufactured and sold on the closest margins of profit possible, the crude drug business has not escaped, it is therefore only possible to make a reasonable profit in marketing the products of the now useless weeds which confront the farmer as a serious problem at every turn. To the one putting thought, economy and perseverance in this work, will come profit which is now merely thrown away.

Many herbs, leaves, barks, seeds, roots, berries and flowers are bought in very large quantities, it being the custom of the larger houses to merely place an order with the collector for all he can collect, without restriction. For example, the barks used from the sassafras roots, from the wild cherry tree, white pine tree, elm tree, tansy herb, jimson weed, etc., run into the hundreds of thousand pounds annually, forming very often the basis of many remedies you buy from your druggist.

The idea prevalent with many, who have at any time considered this occupation, that it is necessary to be familiar with the botanical and Latin names of these weeds, must be abolished. When one of the firms referred to receives a letter asking for the price of Rattle Top Root, they at once know that Cimicifuga Racemosa is meant; or if it be Shonny Haw, they readily understand it to mean Viburnum Prunifolium; Jimson Weed as Stramonium Dotura; Indian Tobacco as Lobelia Inflata; Star Roots as Helonias Roots, and so on throughout the entire list of items.

Should an occasion arise when the name by which an article is locally known cannot be understood, a sample sent by mail will soon be the means of making plain to the buyer what is meant.

Among the many items which it is now necessary to import from Germany, Russia, France, Austria and other foreign countries, which might be produced by this country, the more important are: Dandelion Roots, Burdock Roots, Angelica Roots, Asparagus Roots, Red Clover Heads, or blossoms. Corn Silk, Doggrass, Elder Flowers, Horehound Herb, Motherwort Herb, Parsley Root, Parsley Seed, Sage Leaves, Stramonium Leaves or Jamestown Leaves, Yellow Dock Root, together with many others.

Dandelion Roots have at times become so scarce in the markets as to reach a price of 50c per pound as the cost to import it is small there was great profit somewhere.

These items just enumerated would not be worthy of mention were they of small importance. It is true, though, that with one or two exceptions, the amounts annually imported are from one hundred to five hundred thousand pounds or more.

As plentiful as are Red Clover Flowers, this item last fall brought very close to 20c per pound when being purchased in two to ten-ton lots for the Winter's consumption.

For five years past values for all Crude Drugs have advanced in many instances beyond a proportionate advance in the cost of labor, and they bid fair to maintain such a position permanently. It is safe to estimate the average enhancement of values to be at least 100% over this period; those not reaching such an increased price fully made up for by others which have many times doubled in value.

It is beyond the bounds of possibility to pursue in detail all of the facts which might prove interesting regarding this business, but it is important that, to an extent at least, the matter of fluctuations in values be explained before this subject can be ever in a measure complete.

All items embraced in the list of readily marketable items are at times very high in price and other times very low; this is brought about principally by the supply. It is usually the case that an article gradually declines in price, when it has once started, until the price ceases to make its production profitable.

It is then neglected by those formerly gathering it, leaving the natural demand nothing to draw upon except stocks which have accumulated in the hands of dealers. It is more often the case that such stocks are consumed before any one has become aware of the fact that none has been collected for some time, and that nowhere can any be found ready for the market.

Dealers then begin to make inquiry, they urge its collection by those who formerly did it, insisting still upon paying only the old price. The situation becomes acute; the small lots held are not released until a fabulous price may be realized, thus establishing a very much higher market. Very soon the advanced prices reach the collector, offers are rapidly made him at higher and higher prices, until finally every one in the district is attracted by the high and profitable figures being offered. It is right here that every careful person concerned needs to be doubly careful else, in the inevitable drop in prices caused by the over-production which as a matter of course follows, he will lose money. It will probably take two to five years then for this operation to repeat itself with these items, which have after this declined even to lower figures than before.

In the meantime attention is directed to others undergoing the same experience. A thorough understanding of these circumstances and proper heed given to them, will save much for the collector and make him win in the majority of cases.

Books and other information can be had by writing to the manufacturers and dealers whose advertisements may be found in this and other papers.

The list of American Weeds and Plants as published under above heading having medicinal value and the parts used will be of especial value to the beginner, whether as a grower, collector or dealer.

The supply and demand of medicinal plants changes, but the following have been in constant demand for years. The name or names in parenthesis are also applied to the root, bark, berry, plant, vines, etc., as mentioned:

The following are used in limited quantities only:

The leading botanical roots in demand by the drug trade are the following, to-wit: Ginseng, Golden Seal, Senega or Seneca Snake Root, Serpentaria or Virginia Snake Root, Wild Ginger or Canada Snake Root, Mandrake or Mayapple, Pink Root, Blood Root, Lady Slipper, Black Root, Poke Root and the Docks. Most of these are found in abundance in their natural habitat, and the prices paid for the crude drugs will not, as yet, tempt many persons to gather the roots, wash, cure, and market them, much less attempt their culture. But Ginseng, Golden Seal, Senega, Serpentaria and Wild Ginger are becoming very scarce, and the prices paid for these roots will induce persons interested in them to study their several natures, manner of growth, natural habitat, methods of propagation, cultivation, etc.

This opens up a new field of industry to persons having the natural aptitude for such work. Of course, the soil and environment must be congenial to the plant grown. A field that would raise an abundance of corn, cotton, or wheat would not raise Ginseng or Golden Seal at all. Yet these plants grown as their natures demand, and by one who "knows," will yield a thousand times more value per acre than corn, cotton or wheat. A very small Ginseng garden is worth quite an acreage of wheat. I have not as yet marketed any cultivated Ginseng. It is too precious and of too much value as a yielder of seeds to dig for the market.

Some years ago I dug and marketed, writes a West Virginia party, the Golden Seal growing in a small plot, ten feet wide by thirty feet long, as a test, to see if the cultivation of this plant would pay. I found that it paid extremely well, although I made this test at a great loss. This bed had been set three years. In setting I used about three times as much ground as was needed, as the plants were set in rows eighteen inches apart and about one foot apart in the rows. The rows should have been one foot apart, and the plants about six inches apart in the rows, or less. I dug the plants in the fall about the time the tops were drying down, washed them clean, dried them carefully in the shade and sold them to a man in the city of Huntington, W Va. He paid me $1.00 per pound and the patch brought me $11.60, or at the rate of $1,684.32 per acre, by actual measure and test.

This experiment opened my eyes very wide. The patch had cost me practically nothing, and taking this view only, had paid "extremely well." But, I said, "I made this test at a great loss," which is true, taking the proper view of the case. Suppose I had cut those roots up into pieces for propagation, and stratified them in boxes of sandy loam through the winter, and when the buds formed on them carefully set them in well prepared beds. I would now have a little growing gold mine. The price has been $1.75 for such stock, or 75% more than when I sold, making an acre of such stuff worth $2,948.56. The $11.60 worth of stock would have set an acre, or nearly so. So my experiment was a great loss, taking this view of it.

I am raising, in a small way, Ginseng, Lady Slipper, Wild Ginger and Virginia Snake Root, and am having very good success with all of it. I am also experimenting with some flowering plants, such as Sweet Harbinger, Hepatica, Blood Root, and Blue Bell. I am trying to propagate and grow some shrubs and trees to be used as yard and cemetery trees. Of these my most interesting one is the American Christmas Holly. I have not made much headway with it yet, but I am not discouraged. I know more about it than when I began, and think I shall succeed. There is good demand for Holly at Christmas time, and I can find ready sale for all I can get. I think the plants should sell well, as it makes a beautiful shrub. I think the time has come when the Ginseng and Golden Seal of commerce and medicine will practically all come from the gardens of the cultivators of these plants. I do not see any danger of overproduction. The demand is great and is increasing year by year. Of course, like the rising of a river, the price may ebb and flow, somewhat, but it is constantly going up.

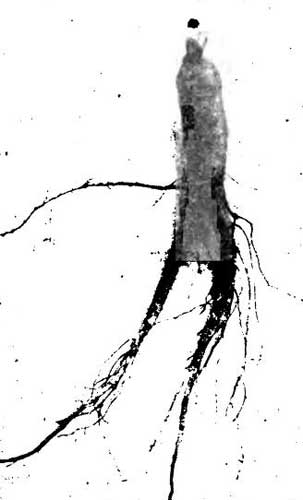

The information contained in the following pages about the habits, range, description and price of scores of root drugs will help hundreds to distinguish the valuable plants from the worthless. In most instances a good photo of the plant and root is given. As Ginseng and Golden Seal are the most valuable, instructions for the cultivation and marketing of same is given in detail. Any root can be successfully grown if the would-be grower will only give close attention to the kind of soil, shade, etc., under which the plant flourishes in its native state.

Detailed methods of growing Ginseng and Golden Seal are given from which it will be learned that the most successful ones are those who are cultivating these plants under conditions as near those as possible which the plants enjoy when growing wild in the forests. Note carefully the nature of the soil, how much sunlight gets to the plants, how much leaf mould and other mulch at the various seasons of the year.

It has been proven that Ginseng and Golden Seal do best when cultivated as near to nature as possible. It is therefore reasonable to assume that all other roots which grow wild and have a cash value, for medicinal and other purposes, will do best when "cultivated" or handled as near as possible under conditions which they thrived when wild in the forests.

Many "root drugs" which at this time are not very valuable — bringing only a few cents a pound — will advance in price and those who wish to engage in the medicinal root growing business can do so with reasonable assurance that prices will advance for the supply growing wild is dwindling smaller and smaller each year. Look at the prices paid for Ginseng and Golden Seal in 1908 and compare with ten years prior or 1898. Who knows but that in the near future an advance of hundreds of per cent. will have been scored on wild turnip, lady's slipper, crawley root, Canada snakeroot, serpentaria (known also as Virginia and Texas snakeroot), yellow dock, black cohosh, Oregon grape, blue cohosh, twinleaf, mayapple, Canada moonseed, blood-root, hydrangea, crane's bill, seneca snakeroot, wild sarsaparilla, pinkroot, black Indian hemp, pleurisy-root, culvers root, dandelion, etc., etc.?

Of course it will be best to grow only the more valuable roots, but at the same time a small patch of one or more of those mentioned above may prove a profitable investment. None of these are apt to command the high price of Ginseng, but the grower must remember that it takes Ginseng some years to produce roots of marketable size, while many other plants produce marketable roots in a year.

There are thousands of land owners in all parts of America that can make money by gathering the roots, plants and barks now growing on their premises. If care is taken to only dig and collect the best specimens an income for years can be had.

History and science have their romances as vivid and as fascinating as any in the realms of fiction. No story ever told has surpassed in interest the history of this mysterious plant Ginseng; the root that for nearly 200 years has been an important article of export to China.

Until a few years ago not one in a hundred intelligent Americans living in cities and towns, ever heard of the plant, and those in the wilder parts of the country who dug and sold the roots could tell nothing of its history and use. Their forefathers had dug and sold Ginseng. They merely followed the old custom.

The natural range of Ginseng growing wild in the United States is north to the Canadian line, embracing all the states of Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, Connecticut, Rhode Island, Delaware, New York, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Maryland, Ohio, West Virginia, Virginia, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin, Kentucky and Tennessee. It is also found in a greater part of the following states: Minnesota, Iowa, Missouri, North and South Carolina, Georgia and Alabama. Until recently the plant was found growing wild in the above states in abundance, especially those states touched by the Allegheny mountains. The plant is also found in Ontario and Quebec, Canada, but has become scarce there also, owing to persistent hunting. It also grows sparingly in the states west of and bordering on the Mississippi river.

Ginseng in the United States was not considered of any medical value until about 1905, but in China it is and has been highly prized for medical purposes and large quantities of the root are exported to that country. It is indeed doubtful if the root has much if any medical value, and the fact that the Chinese prefer roots that resemble, somewhat, the human body, only goes to prove that their use of the root is rather from superstition than real value.

Of late years Ginseng is being cultivated by the Chinese in that country, but the root does not attain the size that it does in America, and the plant from this side will, no doubt, continue to be exported in large quantities.

New York and San Francisco are the two leading cities from which exports are made to China, and in each of these places are many large dealers who annually collect hundreds of thousands of dollars' worth. The most valuable Ginseng grows in New York, the New England states and northern Pennsylvania. The root from southern sections sells at from fifty cents to one dollar per pound less.

Ginseng in the wild or natural state grows largely in beech, sugar and poplar forests and prefers a damp soil. The appearance of Ginseng when young resembles somewhat newly sprouted beans; the plant only grows a few inches the first year. In the fall the stem dies and in the spring the stalk grows up again. The height of the full grown stalk is from eighteen to twenty inches, altho they sometimes grow higher. The berries and seed are crimson (scarlet) color when ripe in the fall. For three or four years the wild plants are small, and unless one has a practical eye will escape notice, but professional diggers have so persistently scoured the hills that in sections where a few years ago it was abundant, it is now extinct.

While the palmy days of digging were on, it was a novel occupation and the "seng diggers," as they are commonly called, go into the woods armed with a small mattock and sack, and the search for the valuable plant begins. Ginseng usually grows in patches and these spots are well known to the mountain residents. Often scores of pounds of root are taken from one patch, and the occupation is a very profitable one. The women as well as the men hunt Ginseng, and the stalk is well known to all mountain lads and lassies. Ginseng grows in a rich, black soil, and is more commonly found on the hillsides than in the lowlands.

Few are the mountain residents who do not devote some of their time to hunting this valuable plant, and in the mountain farm houses there are now many hundred pounds of the article laid away waiting the market. While the fall is the favorite time for Ginseng hunting, it is carried on all summer. When a patch of the root is found the hunter loses no time in digging it. To leave it until the fall would be to lose it, for undoubtedly some other hunter would find the patch and dig it.

How this odd commerce with China arose is in itself remarkable. Many, many years ago a Catholic priest, one who had long served in China, came as a missionary to the wilds of Canada. Here in the forest he noted a plant bearing close resemblance to one much valued as a medicine by the Chinese. A few roots were gathered and sent as a sample to China, and many months afterwards the ships brought back the welcome news that the Chinamen would buy the roots.

Early in its history the value of Ginseng as a cultivated crop was recognized, and repeated efforts made for its propagation. Each attempt ended in failure. It became an accepted fact with the people that Ginseng could not be grown. Now these experimenters were not botanists, and consequently they failed to note some very simple yet essential requirements of the plant. About 1890 experiments were renewed. This time by skilled and competent men who quickly learned that the plant would thrive only under its native forest conditions, ample shade, and a loose, mellow soil, rich in humus, or decayed vegetable matter. As has since been shown by the success of the growers. Ginseng is easily grown, and responds readily to proper care and attention. Under right conditions the cultivated roots are much larger and finer, and grow more quickly than the wild ones.

It may be stated in passing, that Chinese Ginseng is not quite the same thing as that found in America, but is a variety called Panax Ginseng, while ours is Panax Quinquefolia. The chemists say, however, that so far as analysis shows, both have practically the same properties. It was originally distributed over a wide area, being found everywhere in the eastern part of the United States and Canada where soil and locality were favorable.

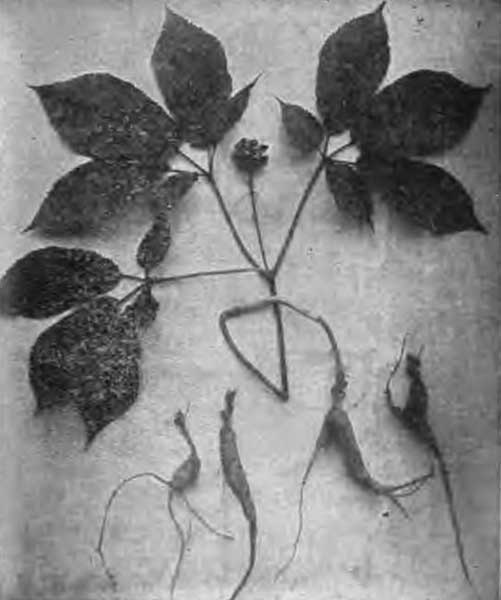

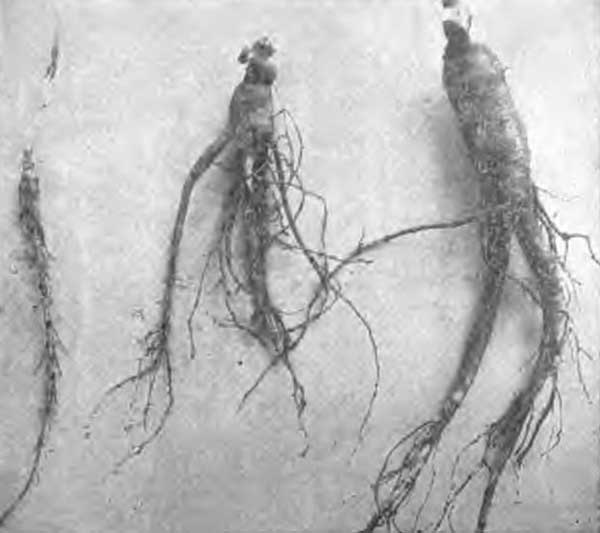

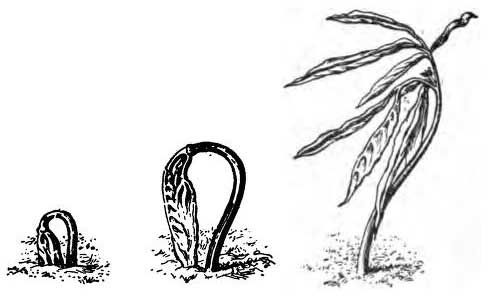

Ginseng has an annual stalk and perennial root. The first year the foliage does not closely resemble the mature plant, having only three leaves. It is usually in its third year that it assumes the characteristic leaves of maturity and becomes a seed-bearer. The photos which accompany give a more accurate idea of the plant's appearance than is possible from a written description. The plants bloom very quickly after sprouting and the berries mature in August and September in most localities. When ripe, the berries are a rich deep crimson and contain usually two seeds each.

The seeds are peculiar in that it usually takes them about eighteen months to germinate and if allowed to become dry in the meantime, the vitality will be destroyed.

Western authorities have heretofore placed little value on Ginseng as a curative agent, but a number of recent investigations seem to reverse this opinion. The Chinese, however, have always placed the highest value upon it and millions have used and esteemed it for untold centuries. Its preparation and uses have never been fully understood by western people.

Our Consuls in China have at various times furnished our government with very full reports of its high value and universal use in the "Flowery Kingdom." From these we learn that "Imperial Ginseng," the highest grade grown in the royal parks and gardens, is jealously watched and is worth from $40.00 to $200.00 per pound. Of course its use is limited to the upper circle of China's four hundred. The next quality comes from Korea and is valued at $15.00 to $35.00 per pound. Its use is also limited to the lucky few. The third grade includes American Ginseng and is the great staple kind. It is used by every one of China's swarming millions who can possibly raise the price. The fourth grade is Japanese Ginseng and is used by those who can do no better.

Mr. Wildman, of Hong Kong, says: "The market for a good article is practically unlimited. There are four hundred million Chinese and all to some extent use Ginseng. If they can once become satisfied with the results obtained from the tea made from American Ginseng, the yearly demand will run up into the millions of dollars worth." Another curious fact is that the Chinese highly prize certain peculiar shapes among these roots especially those resembling the human form. For such they gladly pay fabulous prices, sometimes six hundred times its weight in silver. The rare shapes are not used as medicine but kept as a charm, very much as some Americans keep a rabbit's foot for luck.

Sir Edwin Arnold, that famous writer and student of Eastern peoples, says of its medicinal values: "According to the Chinaman, Ginseng is the best and most potent of cordials, of stimulants, of tonics, of stomachics, cardiacs, febrifuges, and, above all, will best renovate and reinvigorate failing forces. It fills the heart with hilarity while its occasional use will, it is said, add a decade of years to the ordinary human life. Can all these millions of Orientals, all those many generations of men, who have boiled Ginseng in silver kettles and have praised heaven for its many benefits, have been totally deceived? Was the world ever quite mistaken when half of it believed in something never puffed, nowhere advertised and not yet fallen to the fate of a Trust, a Combine or a Corner?"

It has been asked why the Chinese do not grow their own Ginseng. In reply it may be said that America supplies but a very small part indeed of the Ginseng used in China. The bulk comes from Korea and Manchuria, two provinces belonging to China, or at least which did belong to her until the recent Eastern troubles.

Again, Ginseng requires practically a virgin soil, and as China proper has been the home of teeming millions for thousands of years, one readily sees that necessary conditions for the plant hardly exist in that old and crowded country.

A few years ago Ginseng could be found in nearly every woods and thicket in the country. Today conditions are quite different. Ginseng has become a scarce article. The decrease in the annual crop of the wild root will undoubtedly be very rapid from this on. The continued search for the root in every nook and corner in the country, coupled with the decrease in the forest and thicket area of the country, must in a few years exterminate the wild root entirely.

To what extent the cultivated article in the meantime can supplant the decrease in the production of the wild root, is yet to be demonstrated. The most important points in domesticating the root, to my opinion, is providing shade, a necessary condition for the growth of Ginseng, and to find a fertilizer suitable for the root to produce a rapid growth. If these two conditions can be complied with, proper shade and proper fertilizing, the cultivation of the root is simplified. Now the larger wild roots are found in clay soil and not in rich loam. It seems reasonably certain that the suitable elements for the growth of the root is found in clay soil.

The "seng" digger often finds many roots close to the growing stalk, which had not sent up a shoot that year. For how many years the root may lie dormant is not known, nor is it known whether this is caused by lack of cultivation. I have noticed that the cultivated plant did not fail to sprout for five consecutive years. Whether it will fail the sixth year or the tenth is yet unknown. The seed of Ginseng does not sprout or germinate until the second year, when a slender stalk with two or three leaves puts in an appearance. Then as the stalk increases in size from year to year, it finally becomes quite a sizable shrub of one main stalk, from which branch three, four, or even more prongs; the three and four prongs being more common. A stalk of "seng" with eight well arranged prongs, four of which were vertically placed over four others, was found in this section (Southern Ohio) some years ago. This was quite an oddity in the general arrangement of the plant.

Ginseng is a plant found growing wild in the deep shaded forests and on the hillsides thruout the United States and Canada. Less than a score of years ago Ginseng was looked upon as a plant that could not be cultivated, but today we find it is successfully grown in many states. It is surprising what rapid improvements have been made in this valuable root under cultivation. The average cultivated root now of three or four years of age, will outweigh the average wild root of thirty or forty years.

When my brother and I embarked in the enterprise, writes one of the pioneers in the business, of raising Ginseng, we thought it would take twenty years to mature a crop instead of three or four as we are doing today. At that time we knew of no other person growing it and from then until the present time we have continually experimented, turning failures to success. We have worked from darkness to light, so to speak.

In the forests of Central New York, the plant is most abundant on hillsides sloping north and east, and in limestone soils where basswood or butternut predominate. Like all root crops, Ginseng delights in a light, loose soil, with a porous subsoil.

If a cultivated plant from some of our oldest grown seed and a wild one be set side by side without shading, the cultivated one will stand three times as long as the wild one before succumbing to excessive sunlight. If a germinated seed from a cultivated plant were placed side by side under our best mode of cultivation, the plant of the cultivated seed at the end of five years, would not only be heavier in the root but would also produce more seed.

In choosing a location for a Ginseng garden, remember the most favorable conditions for the plant or seed bed are a rich loamy soil, as you will notice in the home of the wild plant. You will not find it on low, wet ground or where the Water stands any length of time, it won't grow with wet feet; it wants well drained soil. A first-class location is on land that slopes to the east or north, and on ground that is level and good. Other slopes are all right, but not as good as the first mentioned. It does not do so well under trees, as the roots and fibers from them draw the moisture from the plant and retard its growth.

The variety of soil is so much different in the United States that it is a hard matter to give instructions that would be correct for all places. The best is land of a sandy loam, as I have mentioned before. Clay land can be used and will make good gardens by mixing leaf mold, rotten wood and leaves and some lighter soil, pulverize and work it thru thoroughly. Pick out all sticks and stones that would interfere with the plants.

Ginseng is a most peculiar plant. It has held a place of high esteem among the Chinese from time immemorial. It hides away from man with seeming intelligence. It is shy of cultivation, the seed germinating in eighteen months as a rule, from the time of ripening and planting. If the seeds become dry they lose, to a certain extent, their germinating power.

The young plant is very weak and of remarkably slow growth. It thrives only in virgin soil, and is very choice in its selection of a place to grow. Remove the soil to another place or cultivate it in any way and it loses its charm for producing this most fastidious plant.

It has a record upon which it keeps its age, or years of its growth, for it passes a great many years in the ground, dormant. I have counted the age upon the record stem of small roots and found their age to be from 30 to 60 years. No plant with which I am acquainted grows as slowly as Ginseng.

A great many superstitious notions are held by the people, generally, in regard to Ginseng. I think it is these natural peculiarities of the plant, together with the fancied resemblance of the root to man, and, also probably its aromatic odor that gives it its charm and value. Destroy it from the earth and the Materia Medica of civilization would lose nothing.

I notice that the cultivated root is not so high in price by some two dollars as the wild root. If the root is grown in natural environment and by natural cultivation, i. e., just let it grow, no Chinaman can tell it from the wild root.

We have at present, writes a grower, in our Ginseng patch about 3,500 plants and will this year get quite a lot of excellent seed. Our Ginseng garden is on a flat or bench on a north hillside near the top, that was never cleared. The soil is a sandy loam and in exposure and quality naturally adapted to the growth of this plant. The natural growth of timber is walnut, both black and white, oak, red bud, dogwood, sugar, maple, lin, poplar and some other varieties.

We cultivate by letting the leaves from the trees drop down upon the bed in the fall as a mulch and then in the early spring we burn the leaves off the bed. Our plants seem to like this treatment very well. They are of that good Ginseng color which all Ginseng diggers recognize as indicative of good sized, healthy roots.

I have had much experience in hunting the wild Ginseng roots, says another, and have been a close observer of its habits, conditions, etc. High shade is best with about one-half sun. The root is found mostly where there is good ventilation and drainage. A sandy porous loam produces best roots. Plants in dense shade fail to produce seed in proportion to the density of the shade. In high one-half shade they produce heavy crops of seed. Coarse leaves that hold water will cause disease in rainy seasons. No leaves or mulch make stalks too low and stunted.

Ginseng is very wise and knows its own age. This age the plant shows in two ways. First, by the style of the foliage which changes each year until it is four years old. Second, the age can be determined by counting the scars on the neck of the bud-stem. Each year the stalk which carries the leaves and berries, goes down, leaving a scar on the neck or perennial root from which it grew. A new bud forms opposite and a little above the old one each year. Counting these stalk scars will give the age of the plant.

I have seen some very old roots and have been told that roots with fifty scars have been dug. The leaf on a seedling is formed of three small parts on a stem, growing directly out of a perennial root and during the first year it remains that shape. The second year the stem forks at the top and each fork bears two leaves, each being formed of five parts. The third year the stem forks three ways and bears three leaves, each formed of five parts, much like the Virginia creeper.

Now the plant begins to show signs of bearing seed and a small button-shaped cluster of green berries can be seen growing in the forks of the stalk at the base of the leaf stem. The fourth year the perennial stalk grows as large around as an ordinary lead pencil and from one foot to twenty inches high. It branches four ways, and has four beautiful five-pointed leaves, with a large well-formed cluster of berries in the center. After the middle of June a pale green blossom forms on the top of each berry. The berries grow as large as a cherry pit and contain two or three flat hard seeds. In September they turn a beautiful red and are very attractive to birds and squirrels. They may be gathered each day as they ripen and should be planted directly in a bed, or put in a box of damp, clean sand and safely stored. If put directly in the ground they will sprout the first year, which advantage would be lost if stored dry.

A word to trappers about wild roots. When you find a plant gather the seed, and unless you want to plant them in your garden, bury them in the berry about an inch or inch and a half deep in some good, rich, shady place, one berry in each spot. Thus you will have plants to dig in later years, you and those who come after you. Look for it in the autumn after it has had time to mature its berries. Do not take up the little plants which have not yet become seed bearers.

The forest is the home of the Ginseng plant and the closer we follow nature the better results we get. I am growing it now under artificial shade; also in the forest with natural shade, says an Ohio party. A good shade is made by setting posts in the ground, nail cross-pieces on these, then cover with brush. You must keep out the sun and let in the rain and this will do both. Another good shade is made by nailing laths across, allowing them to be one-half inch apart. This will allow the rain to pass thru and will keep the sun out. Always when using lath for shade allow them to run east and west, then the sun can't shine between them.

In selecting ground for location of a Ginseng garden, the north side of a hill is best, altho where the ground is level it will grow well. Don't select a low marshy piece of ground nor a piece too high, all you want is ground with a good drainage and moisture. It is the opinion of some people that in a few years the market will be glutted by those growing it for sale. I will venture to say that I don't think we can grow enough in fifty years to over-run the market. The demand is so great and the supply so scarce it will be a long time before the market will be affected by the cultivated root.

The market has been kept up entirely in the past by the wild root, but it has been so carelessly gathered that it is almost entirely exhausted, so in order to supply this demand we must cultivate this crop. I prepare my beds five feet wide and as long as convenient. I commence by covering ground with a layer of good, rich, loose dirt from the woods or well-rotted manure. Then I spade it up, turning under the rich dirt. Then I cover with another layer of the same kind of dirt in which I plant my seed and roots.

After I have them planted I cover the beds over with a layer of leaves or straw to hold the moisture, which I leave on all winter to protect them from the cold. In the spring I remove a part of the leaves (not all), they will come up thru the leaves as they do in their wild forest.

All the attention Ginseng needs after planting is to keep the weeds out of the beds. Never work the soil after planting or you will disturb the roots. It is a wild plant and we must follow nature as near as possible.

Ginseng can be profitably grown on small plots if it is cared for properly. There are three things influencing its growth. They are soil, shade and treatment. In its wild state the plant is found growing in rich leaf mold of a shady wood. So in cultivation one must conform to many of the same conditions in which the plant is found growing wild.

In starting a bed of Ginseng the first thing to be considered is the selection of soil. Tho your soil be very rich it is a good plan to cover it with three or four inches of leaf mold and spade about ten inches deep so that the two soils will be well mixed. Artificial shade is preferable at all times because trees take nearly all the moisture and strength out of the soil.

When the bed is well fitted, seed may be sown or plants may be set out. The latter is the quicker way to obtain results. If seeds are sown the young grower is apt to become discouraged before he sees any signs of growth, as it requires eighteen months for their germination. The cheapest way to get plants is to learn to recognize them at sight, then go to the woods and try to find them. With a little practice you will be able to tell them at some distance. Much care should be taken in removing the plant from the soil. The fewer fibers you break from the root, the more likely it will be to grow. Care should also be taken not to break the bud on top of the root. It is the stalk of the plant starting for the next year, and is very noticeable after June 1st. If it be broken or harmed the root will have no stalk the next season.

It is best to start a Ginseng garden on a well drained piece of land, says a Dodge County, Wisconsin, grower. Run the beds the way the hill slopes. Beds should only be four to five feet wide so that they can be reached, for walking on the beds is objectionable. Make your walks about from four to six inches below the beds, for an undrained bed will produce "root rot." The ground should be very rich and "mulchy." Use well rotted horse manure in preparing the beds, for fresh manure will heat and hurt the plants. Use plenty of woods dirt, but very little manure of any kind.

Set plants about six inches each way, and if you want to increase the size of the root, pinch off the seed bulb. In the fall when the tops have died down, cover the beds about two inches deep with dead leaves from the woods. We make our shades out of one-inch strips three inches wide and common lath. The north and west fence should be more tight to keep cold winds out. Eastern and southern side tight, two feet from the ground. From the two feet to top you may use ordinary staves from salt barrels or so nailed one inch apart. Have your Ginseng garden close to the house, for Ginseng thieves become numerous.

I was raised in the country on a farm and as near to nature as it is possible to get, and have known a great deal of Ginseng from my youth up. Twenty-five years ago it was 75 cents a pound, and now it is worth ten times as much. Every one with any experience in such matters knows that if radishes or turnips are planted in rich, old soil that has been highly fertilized they will grow large and will be strong, hot, pithy and unpalatable. If planted in rich, new soil, they will be firm, crisp, juicy and sweet. This fact holds good with Ginseng.

If planted in old ground that is highly fertilized, the roots will grow large, but the flavor is altogether different from that of the wild root, and no doubt specimens of large sizes are spongy and unpalatable to the Celestials compared to that of the wild root.

If planted in rich, new ground and no strong fertilizer used, depending entirely upon the rich woods soil for enriching the beds, the flavor is bound to be exactly as that of the wild root. When the growers wake up to this fact, and dig their roots before they become too large, prices will be very satisfactory and the business will be on a sound basis.

We will begin in a systematic way, with the location, planting and preparing of the ground for the Ginseng garden, writes a successful grower — C. H. Peterson — of Blue Earth County, Minn.

In choosing a location for a Ginseng garden, select one having a well-drained soil. Ginseng thrives best in wood loam soil that is cool and mellow, although any good vegetable garden soil will do very well. A southern slope should be avoided, as the ground gets too warm in summer and it also requires more shade than level or northern slope does. It is also apt to sprout too early in the spring, and there is some danger of its getting frosted, as the flower stem freezes very easily and no seed is the result.

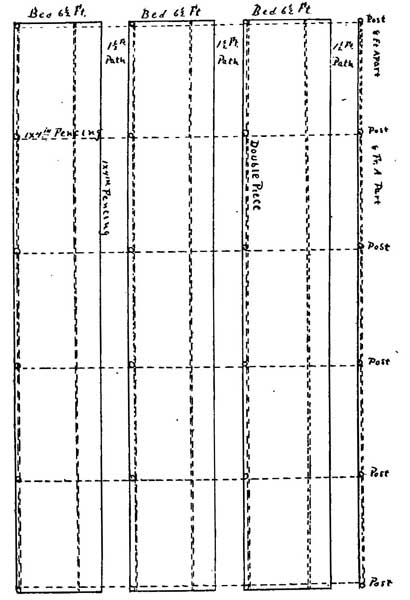

Then again if you locate your garden on too low ground the roots are apt to rot and the freezing and thawing of wet ground is hard on Ginseng. Laying out a garden nothing is more important than a good system both for looks, convenience and the growth of your roots later on. Do your work well as there is good money in raising Ginseng, and for your time you will be well repaid. Don't make one bed here and another there and a path where you happen to step, but follow some plan for them. I have found by experience that the wider the beds are, the better, providing that their width does not exceed the distance that you can reach from each path to center of bed to weed. For general purposes for beds 6 1/2 ft. is used for paths 1 1/2 ft. A bed 6 1/2 ft. wide gives you 3 1/4 ft. to reach from each path to center of bed without getting on the beds, which would not be advisable. An 18 in. path is none too wide after a few years' growth, as the plants nearly cover this with foliage. This size beds and paths are just the right width for the system of lath shading I am using, making the combined distance across bed and path 8 ft., or 16 ft. for two beds and two paths, just right to use a 1x4 rough 16 ft. fencing board to run across top of posts described later on.

Now we will lay out the garden by setting a row of posts 8 ft. apart the length you desire to make your garden. Then set another row 8 ft. from first row running parallel with first row, and so on until desired width of your garden has been reached. Be sure to have post line up both ways and start even at ends. Be sure to measure correctly. After all posts are set run a 1x4 in. rough fence board across garden so top edge is even at top of post and nail to post. The post should be about 8 ft. long so when set would be a trifle over 6 ft. above ground. This enables a person to walk under shading when completed. It is also cooler for your plants. In setting the posts do not set them too firm, so they can be moved at top enough to make them line up both ways. After the 1x4 in. fence board is put on we will nail on double pieces.

Take a 1x6 rough fence board 16 ft. long and rip it so as to make two strips, one 3 1/2 and the other 2 1/2 inches wide, lay the 3 1/2 in. flat and set the 2 1/2 in. strip on edge in middle of other strip and nail together. This had better be done on the ground so it can be turned over to nail. Then start at one side and run this double piece lengthwise of your garden or crosswise of the 1x4 in. fence board nailed along top of post and nail down into same. It may be necessary to nail a small piece of board on side of the 1x4 in. board where the joints come. Then lay another piece similar to this parallel with first one, leaving about 49 1/2 in. between the two. This space is for the lath panel to rest on the bottom piece of the double piece. Do not put double pieces so close that you will have to crowd the lath panels to get them in, but leave a little room at end of panel. You will gain about 1 1/2 in. for every double piece used in running across the garden. This has to be made up by extending over one side or the other a piece of 1x4 board nailed to end of 1x4 board nailed at top posts. Let this come over the side you need the shade most. Begin from the side you need the shade least and let it extend over the other side.

It is advisable to run paths on outside of garden and extend the shading out over them. On sides lath can be used unless otherwise shaded by trees or vines. It will not be necessary to shade the north side if shading extends out over end of beds several feet. Give your plants all the air you can. In this system of shading I am using I have figured a whole lot to get the most convenient shading as well as a strong, substantial one without the use of needless lumber, which means money in most places. It has given good satisfaction for lath shade so far. Being easily built and handy to put on in spring and take off in fall.

Now don't think I am using all lath shade, as I am not. In one part of garden I am using lath and in another part I am using some good elm trees. I think, however, that the roots make more rapid growth under the lath shade, but the trees are the cheaper as they do not rot and have to be replaced. They also put on their own shade. The leaves when the proper time comes also removes it when the time comes in the fall and also mulches the beds at the same time.

We will now plan out the beds and paths. Use 1x4 in. rough 16 ft. fence boards on outside row of posts next to ground, nail these to posts, continue and do likewise on next row of posts, and so on until all posts have boards nailed on same side of them as first one, the post being just on inside edge of your beds. Then measure 6 1/2 ft. toward next board, drive a row of stakes and nail a board of same width to same the length of your garden that will make 18 in. between last row of boards and boards on next row nailed to post for the path.

These boards answer several purposes, viz., keep people from walking on beds, elevates beds above paths, holds your mulching of leaves and adds to the appearance of your garden. After beds are made by placing the boards spade the ground about a foot deep all over the bed so as to work it up in good shape. After this is done fork it over with a six-tine fork. If bed is made in summer for fall or spring planting it is well to work it over several times during the summer, as the ground cannot be too mellow. This will also help kill the weeds. Then just before planting rake it down level.

In case beds are made in woods cut, or better, grub out all trees not needed for shade, and if tree roots are not too large cut out all next to the surface running inside of boards in beds, and work the same as other beds. Lay out your beds same as for lath shade with paths between them. Don't try to plant Ginseng in the woods before making it into beds, as you will find it unsatisfactory.

We will now make the lath panel before mentioned.

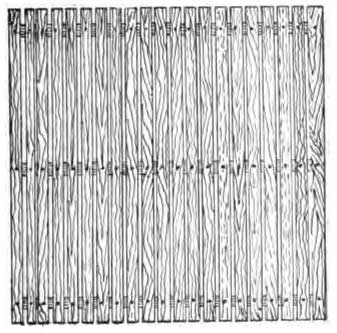

Place three laths so that when the laths are laid crosswise one of the laths will be in the middle and the other two, one at each end two inches from end. Can be placed at the end, but will rot sooner. Then begin at end of the three laths and nail lath on, placing them 1/2 in. apart until other end is reached, and if lath is green put closer together to allow for shrinkage. If you have many panels to make, make a table out of boards and lay strips of iron fastened to table where the three lath comes, so as to clinch nails when they strike the iron strips, which will save a lot of work. Gauges can also be placed on side of table to lay lath so they will be even at ends of panels when finished. Then lay panels in your double pieces on your garden, and if garden is not located in too windy a locality they will not blow out without nailing, and a wire drawn tight from end to end of garden on top of panels will prevent this, and is all that is necessary to hold them in place.

In Central New York, under favorable conditions, Ginseng plants should be coming up the last of April and early May, and should be in the ground by or before April 1st, to give best results. Healthy roots, taken up last of March or early April will be found covered with numerous fine hair-like rootlets. These are the feeders and have all grown from the roots during the spring. They should be well established in the soil before plants appear. Fifteen minutes exposure to the sun or wind will seriously injure and possibly destroy these fine feeders, forcing the roots to throw out a second crop of feeders.

Considering these conditions and frequent late seasons, our advice to beginners is, wait until fall for transplanting roots. But we are not considering southern conditions. Southern growers must be governed by their own experience and climatic conditions. It may be a matter of convenience sometimes for a northern grower to take up one or two year seedlings and transplant to permanent beds in spring. If conditions are favorable so the work can be done in March or early April, it may be allowable. Have ground ready before roots are taken up. Only take up a few at a time, protect from sun and wind, transplant immediately.

Spring sowing of old seed. By this we mean seed that should have been sowed the fall before when one year old, but has been kept over for spring sowing.

There is other work that can be done quite early in the Ginseng gardens. All weeds that have lived thru the winter should be pulled as soon as frost is out of ground. They can be pulled easier then than any other time and more certain of getting the weed root out. Mulching should be looked to. When coarse material like straw or leaves has been used, it should be loosened up so air can get to the soil and the plants can come up thru the mulch. If very heavy, perhaps a portion of the mulch may need to be removed, but don't! don't! take mulch all off from beds of set roots. Seed beds sown last fall will need to be removed about time plants are starting up. But seed beds should have been mulched with coarse leaf loam, or fine vegetable mulch, and well rotted horse manure (half and half), thoroughly mixed together, this mulch should have been put on as soon as seeds were sown and covered with mulch one inch deep. If this was not done last fall it should be put on this spring as soon as snow is off beds.

There is another point that needs careful attention when plants are coming up. On heavy soil plants are liable to be earth bound; this is quite likely to occur on old beds that have not been mulched and especially in dry seasons. As the Ginseng stalk comes out of the ground doubled (like an inverted U) the plant end is liable to be held fast by the hard soil, causing injury and often loss of plants. A little experience and careful observation will enable one to detect earth bound plants. The remedy is to loosen soil around the plant. A broken fork tine about eight inches long (straightened) and drive small end in a piece of broom handle about four inches long for a handle, flatten large end of tine like a screwdriver; this makes a handy tool for this work. Force it into soil near plant, give a little prying movement, at same time gently pull on plant end of stalk until you feel it loosen, do not try to pull it out, it will take care of itself when loosened. There is not likely to be any trouble, if leaves appear at the surface of soil. This little spud will be very useful to assist in pulling weed roots, such as dandelion, dock, etc.

Where movable or open shades are used, they need not be put on or closed till plants are well up; about the time leaves are out on trees is the general rule. But one must be governed to some extent by weather and local conditions. If warm and dry, with much sun, get them on early. If wet and cool, keep them off as long as practicable, but be ready to get them on as soon as needed.

I would advise a would-be grower of Ginseng to visit, if possible, some gardens of other growers and learn all they can by inquiry and observation.

In selecting a place for your garden, be sure it has good drainage, as this one feature may save you a good deal of trouble and loss from "damping off," "wilt," and other fungus diseases which originate from too damp soil.

A light, rich soil is best. My opinion is to get soil from the forest, heap up somewhere for a while thru the summer, then sift thru sand sieve or something similar, and put about two inches on top of beds you have previously prepared by spading and raking. If the soil is a little heavy some old sawdust may be mixed with it to lighten it. The woods dirt is O. K. without using any commercial fertilizers. The use of strong fertilizers and improper drying is responsible for the poor demand for cultivated root. The Chinese must have the "quality" he desires and if flavor of root is poor, will not buy.

I wonder how many readers know that Ginseng can be grown in the house? writes a New York dealer.

Take a box about 5 inches deep and any size you wish. Fill it with woods dirt or any light, rich soil. Plant roots in fall and set in cellar thru the winter. They will begin to come up about April 1st, and should then be brought out of cellar. I have tried this two seasons. Last year I kept them by a window on the north side so as to be out of the sunshine. Window was raised about one inch to give ventilation. Two plants of medium size gave me about 100 seeds.

This season I have several boxes, and plants are looking well and most of them have seed heads with berries from one-third to three-fourths grown. They have been greatly admired, and I believe I was the first in this section to try growing Ginseng as a house plant.

As to the location for a Ginseng garden, I have for the past two years been an enthusiast for cultivation in the natural forest, writes L. C. Ingram, M. D., of Minnesota. It is true that the largest and finest roots I have seen were grown in gardens under lattice, and maintaining such a garden must be taken into account when balancing your accounts for the purpose of determining the net profits, for it is really the profits we are looking for.

The soil I have found to be the best, is a rich black, having a good drain, that is somewhat rolling. As to the direction of this slope I am not particular so long as there is a rich soil, plenty of shade and mulch covering the beds.

The selection of seed and roots for planting is the most important item confronting the beginner. Considerable has been said in the past concerning the distribution among growers of Japanese seed by unscrupulous seed venders. It is a fact that Japanese Ginseng seed have been started in a number of gardens, and unless successfully stamped out before any quantity finds its way into the Chinese market, the Ginseng industry in America, stands in peril of being completely destroyed. Should they find our root mixed, their confidence would be lost and our market lost. Every one growing Ginseng must be interested in this vital point, and if they are suspicious of any of their roots being Japanese, have them passed upon by an expert, and if Japanese, every one dug.

It is a fact that neighboring gardens are in danger of being mixed, as the bees are able to do this in carrying the mixing pollen. The safest way to make a start is by procuring seed and roots from the woods wild in your own locality. If this cannot be done then the seed and roots for a start should be procured from a reliable party near you who can positively guarantee the seed and roots to be genuine American Ginseng. We should not be too impatient and hasty to extend the garden or launch out in a great way. Learn first, then increase as the growth of new seed will permit.

The next essential thing is the proper preparation of the soil for the planting of the seeds and roots. The soil must be dug deep and worked perfectly loose same as any bed in a vegetable garden. The beds are made four or five feet wide and raised four to six inches above the paths, which are left one and a half to two feet wide. I have had seed sown on the ground and covered with dirt growing beside seed planted in well made beds and the contrast in size and the thriftiness of roots are so great when seen, never to be forgotten. The seedlings growing in the hard ground were the size of oat kernels, those in the beds beside them three to nine inches long and weighing from four to ten times as much per root.

In planting the seed all that is necessary is to scatter the stratified seed on top of the prepared bed so they will be one or two inches apart, then cover with loose dirt from the next bed then level with back of garden rake. They should be one-half to one inch covered. Sawdust or leaves should next be put on one to two inches for a top dressing to preserve moisture, regulate heat, and prevent the rains from packing the soil.

The best time to do all planting is in the spring. This gives the most thrifty plants with the least number missing. When the plants are two years old they must be transplanted into permanent beds. These are prepared in the same manner as they were for the seed. A board six inches wide is thrown across the bed, you step on this and with a spade throw out a ditch along the edge of the board. In this the roots are set on a slant of 45 degrees and so the bud will be from one to two inches beneath the surface. The furrow is then filled and the board moved its width. By putting the roots six inches apart in the row and using a six-inch board your plants will be six inches each way, which with most growers have given best results. When the roots have grown three years in the transplanted beds they should be ready to dig and dry for market. They should average two ounces each at this time if the soil was rich in plant food and properly prepared and cared for.

The plants require considerable care and attention thru each summer. Moles must be caught, blight and other diseases treated and the weeds pulled, especially from among the younger plants. As soon as the plants are up in the spring the seed buds should be clipped from all the plants except those finest and healthiest plants you may save for your seed to maintain your garden. The clipping of the seed buds is very essential, because we want the very largest and best flavored root in the shortest time for the market. Then if we grow bushels of seed to the expense of the root, it is only a short time when many thousands of pounds of root must compete with our own for the market and lower the price.

In several years experience growing Ginseng, says a well known grower, I have had no trouble from blight when I shade and mulch enough to keep the soil properly cool, or below 65 degrees, as you will find the temperature in the forests, where the wild plants grow best, even during summer days.

Some years ago I allowed the soil to get too warm, reaching 70 degrees or more. The blight attacked many plants then. This proved to me that growing the plants under the proper temperature has much to do with blight.

When fungus diseases get upon wild plants, that is plants growing in the forest, in most cases it can be traced to openings, forest fires and the woodman's ax. This allows too much sun to strike the plants and ground in which they are growing. If those engaged, or about to engage, in Ginseng growing will study closely the conditions under which the wild plants flourish best, they can learn much that they will only find out after years of experimenting.

Mr. L. E. Turner in a recent issue of "Special Crops" says: We cannot depend on shade alone to keep the temperature of the soil below 65 degrees — the shade would have to be almost total. In order to allow sufficient light and yet keep the temperature down, we must cover the ground with a little mulch. The more thoroughly the light is diffused the better for the plants. Now, when we combine sufficient light with say one-half inch of clean mulch, we are supplying to the plants their natural environment, made more perfect in that it is everywhere alike.

The mulch is as essential to the healthy growth of the Ginseng plant as clothing is to the comfort and welfare of man; it can thrive without it no more than corn will grow well with it. These are plants of opposite nature. Use the mulch and reduce the shade to the proper density. The mulch is of the first importance, for the plants will do much better with the mulch and little shade than without mulch and with plenty of shade.

Ginseng is truly and wholly a savage. We can no more tame it than we can the partridge. We can lay out a preserve and stock it with Ginseng as we would with partridges, but who would stock a city park with partridges and expect them to remain there? We cannot make a proper Ginseng preserve under conditions halfway between a potato patch and a wild forest, but this is exactly the trouble with a large share of Ginseng gardens. They are just a little too much like the potato patch to be exactly suited to the nature of Ginseng. The plant cannot thrive and remain perfectly healthy under these conditions; we may apply emulsions and physic, but we will find it to be just like a person with an undermined constitution, it will linger along for a time subject to every disease that is in the air and at last some new and more subtle malady will, in spite of our efforts, close its earthly career.

Kind readers, I am in a position to know thoroughly whereof I write, for I have been intimate for many years with the wild plants and with every shade of condition under which they manage to exist. I have found them in the valley and at the hilltop, in the tall timber and the brambled "slashing," but in each place were the necessary conditions of shade and mulch. The experienced Ginseng hunter comes to know by a kind of instinct just where he will find the plant and he does not waste time searching in unprofitable places. It is because he understands its environment. It is the environment he seeks — the Ginseng is then already found. The happy medium of condition under which it thrives best in the wild state form the process of healthy culture.

Mr. Wm E. Mowrer, of Missouri, is evidently not in favor of the cloth shading. I think if he had thoroughly water-proofed the cloth it would have withstood the action of the weather much better. It would have admitted considerably less light and if he had given enough mulch to keep the soil properly cool and allowed space enough for ventilation, he would not have found the method so disastrous. We will not liken his trial to the potato patch, but to the field where tobacco is started under canvas. A tent is a cool place if it is open at the sides and has openings in the top and the larger the tent the cooler it will be. Ginseng does splendidly under a tent if the tent is built expressly with regard to the requirements of Ginseng.

In point of cheapness a vine shading is yet ahead of the cloth system. The wild cucumber vine is best for this purpose, for it is exactly suited by nature to the conditions in a Ginseng garden. It is a native of moist, shady places, starts early, climbs high and rapidly. The seeds may be planted five or six in a "hill" in the middle of the beds, if preferred, at intervals of six or seven feet, and the vines may be trained up a small pole to the arbor frame. Wires, strings or boughs may be laid over the arbor frame for the vines to spread over. If the shade becomes too dense some of the vines may be clipped off and will soon wither away. Another advantage of the wild cucumber is that it is very succulent, taking an abundance of moisture and to a great extent guards against excessive dampness in the garden. The vines take almost no strength from the soil. The exceeding cheapness of this method is the great point in its favor. It is better to plant a few too many seeds than not enough, for it is easy to reduce the shade if too dense, but difficult to increase it in the summer if too light.

This disease threatens seriously to handicap us in the raising of Ginseng, says a writer in "Special Crops." It does down, but is giving us trouble all over the country. No section seems to be immune from it, tho all seem to be spraying more or less. I know of several good growers whose gardens have gone down during the last season and this, and they state that they began early and sprayed late, but to no decided benefit. What are we to do? Some claim to have perfect success with spraying as their supposed prevention.

Three years ago I began to reason on this subject and in my rambles in the woods, I have watched carefully for this disease, as well as others on the wild plant, and while I have now and then noted a wild plant that was not entirely healthy, I have never seen any evidence of blight or other real serious disease. The wild plant usually appears ideally healthy, and while they are smaller than we grow in our gardens, they are generally strikingly healthful in color and general appearance. Why is this so? And why do we have such a reverse of things among our gardens?

I will offer my ideas on the subject and give my theories of the causes of the various diseases and believe that they are correct and time will prove it. At least I hope these efforts of mine will be the means of helping some who are having so much trouble in the cultivation of Ginseng. The old saw that the "proof of the pudding is in chewing the bag," may be amply verified by a visit to my gardens to show how well my theories have worked so far. I will show you Ginseng growing in its highest state of perfection and not a scintilla of blight or any species of alternaria in either of them, while around me I scarcely know of another healthy garden.

To begin with, moisture is our greatest enemy; heat next; the two combined at the same time forming the chief cause for most diseases of the plant.

If the soil in our gardens could be kept only slightly moist, as it is in the woods, and properly shaded, ventilated and mulched, I am sure such a thing as blight and kindred diseases would never be known. The reason for this lies in the fact that soil temperature is kept low and dry. The roots, as is well known, go away down in the soil, because the temperature lower down is cooler than at the surface.

Here is where mulch plays so important a part because it protects the roots from so much heat that finds its way between the plants to the top of the beds. The mulch acts as a blanket in keeping the heat out and protecting the roots thereby. If any one doubts this, just try to raise the plants without mulch, and note how some disease will make its appearance. The plant will stand considerable sun, however, with heavy enough mulch. And the more sun it can take without harm, the better the root growth will be. Too much shade will show in a spindling top and slender leaves, and invariable smallness of root growth, for, let it be borne in mind always, that the plant must derive more or less food from the top, and it is here that the fungi in numerous forms proceed to attack.

The plant will not grow in any other atmosphere but one surcharged with all kinds of fungi. This is the natural environment of the plant and the only reason why the plants do not all become diseased lies in the plain fact that its vitality is of such a high character that it can resist the disease, hence the main thing in fighting disease is to obtain for the plant the best possible hygienic surroundings and feed it with the best possible food and thus nourish it to the highest vitality.

I am a firm believer in spraying of the proper kind, but spraying will not keep a plant free from disease with other important conditions lacking. Spraying, if heavily applied, is known as a positive injury to the plant, despite the fact that many claim it is not, and the pity is we should have to resort to it in self-defense. The pores of the leaflets are clogged up to a greater or less extent with the deposited solution and the plant is dependent to this extent of its power to breathe.

Coat a few plants very heavily with spray early in the season and keep it on and note how the plants struggle thru the middle of a hot day to get their breath. Note that they have a sluggish appearance and are inclined to wilt. These plants are weakened to a great extent and if an excess of moisture and heat can get to them, they will perhaps die down. Another thing: Take a plant that is having a hard time to get along and disturb the root to some extent and in a day or two notice spots come upon it and the leaves begin to show a wilting. Vitality disturbed again.

The finest plants I have ever found in the woods were growing about old logs and stumps, where the soil was heavily enriched with decaying wood. A good cool spot, generally, and more or less mulch, and if not too much shade present. Where the shade was too dense the roots were always small. I have in some instances found some very fine roots growing in the midst of an old stump with no other soil save the partially rotted stump dirt, showing thus that Ginseng likes decaying wood matter. Upon learning this, I obtained several loads of old rotten sawdust, preferably white oak or hickory and my bed in my gardens is covered at least two inches with it under the leaf mulch. This acts as a mulch and natural food at one and the same time. The leaves decay next to the soil and thus we supply leaf mold.

This leaf mold is a natural requirement of the plant and feeds it also constantly. A few more leaves added each fall keep up the process and in this way we are keeping the plant wild, which we must do to succeed with it, for Ginseng can not be greatly changed from its nature without suffering the consequences. This is what is the matter now with so many of us. Let's go back to nature and stay there, and disease will not give us so much trouble again.

One more chief item I forgot to mention was the crowding of the plants together. The smaller plants get down under the larger and more vigorous and have a hard struggle for existence. The roots do not make much progress under these conditions, and these plants might as well not be left in the beds. And also note that under those conditions the beds are badly ventilated and if any plants are found to be sickly they will be these kind. I shall plant all my roots henceforth at least ten inches apart each way and give them more room for ventilation and nourishment. They get more chance to grow and will undoubtedly make firm root development and pay largely better in the end. Corn cannot be successfully cultivated in rows much narrower than four feet apart and about two stalks to the hill. All farmers know if the hills are closer and more stalks to the hill the yield will be much less.

At this point I would digress to call attention to the smallness of root development in the woods, either wild or cultivated, because the trees and tree roots sap so much substance from the soil and other weeds and plants help to do the same thing. The shade is not of the right sort, too dense or too sparse in places, and the plants do not make quick growth enough to justify the growing under such conditions, and while supposed to be better for health of plants, does not always prove to be the case. I have seen some gardens under forest shade that blighted as badly as any gardens.

So many speak of removing the leaves and mulch in the spring from the beds. Now, this is absolutely wrong, because the mulch and leaves keep the ground from becoming packed by rains, preserves an even moisture thru the dry part of the season and equalizes the temperature. Temperature is as important as shade and the plants will do better with plenty of mulch and leaves on the beds and considerable sun than with no mulch, dry hard beds and the ideal shade. Roots make but little growth in dry, hard ground. Pull your weeds out by hand and protect your garden from the seng digger thru the summer and that will be your cultivation until September or October when you must transplant your young roots into permanent beds, dig and dry the mature roots.

The following is from an article on "The Alternaria Blight of Ginseng" by H. H. Whetzel, of Cornell University, showing that the author is familiar with the subject:

The pioneer growers of Ginseng thought they had struck a "bonanza." Here was a plant that seemed easily grown, required little attention after it was once planted, was apparently free from all diseases to which cultivated plants are heir and was, besides, extremely valuable. Their first few crops bore out this supposition. No wonder that a "Ginseng craze" broke out and that men sat up nights to figure out on paper the vast fortunes that were bound to accrue to those who planted a few hundred seeds at three cents each and sold the roots in five years at $12.00 a pound.