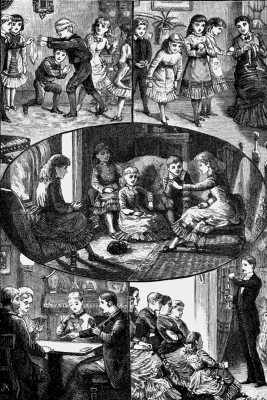

IN-DOOR AMUSEMENTS.

BLIND MAN'S BUFF.NINE PINS.

FIRESIDE FUN.

WHIST.PARLOUR MAGIC.

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Cassell's Book of In-door Amusements, Card Games, and Fireside Fun, by Various This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: Cassell's Book of In-door Amusements, Card Games, and Fireside Fun Author: Various Release Date: June 4, 2015 [EBook #49137] Last Updated: June 8, 2015 Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK AMUSEMENTS *** Produced by Chris Curnow, Cindy Horton and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

The cover image was created by the transcriber, using an image from the book's original frontispiece, and is placed in the public domain.

View larger versions of some illustrations by clicking on those with a border. This may or may not be supported by your device.

With Numerous Illustrations.

THIRD EDITION.

Cassell, Petter, Galpin & Co.:

LONDON, PARIS & NEW YORK.

[ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.]

This Work is a companion volume to Cassell's Book of Sports and Pastimes. As the latter—with the exception of the special sections on "Recreative Science," "The Workshop," and "Home Pets"—is largely occupied with games and sports which are usually carried on out-of-doors, it will be seen that the present book, which is almost exclusively devoted to indoor games of various kinds, forms a very fitting supplement to the other.

It has been the constant aim of the different writers to convey their information in plain, accurate, direct fashion, so that readers may come to understand, on the first occasion of consulting it, that Cassell's Book of Indoor Amusements, Card Games, and Fireside Fun is a Work that deserves their confidence, and may accordingly acquire the habit of referring to it, as a matter of course, when in doubt on any point connected with their favourite games, or when desirous of learning new amusements. Reference has now and again been unavoidably made to outdoor games, either by way of comparison or suggestion for further details. In such cases the reference always has been to the companion volume already mentioned, so that readers possessing the two books will have no difficulty in following the instructions of the Author. In the section on "Parlour Magic" no trick has been described involving the use of apparatus in any degree elaborate. The[4] one or two tricks of a formidable character which are there fully explained have been selected—as the text, in fact, expressly states—to show young conjurers what can really be done with the help of long training and expensive appliances.

In conclusion, the Editor hopes that this work may be the means of introducing many a new game to the young folk for whom it has been his happiness to cater. He will not tell them that all play and no work make Jack a stupid boy, because he has no doubt that his readers are just as fond of their lessons as they are of merry romps or quieter games.

ROUND OR PARLOUR GAMES.

| PAGE | |

| Acting Proverbs | 9 |

| Acting Rhymes | 9 |

| Adjectives | 10 |

| Adventurers, The | 10 |

| Æsop's Mission | 11 |

| Alphabet Games | 11 |

| Artists' Menagerie, The | 12 |

| Baby Elephant, The | 12 |

| Bird-catcher, The | 13 |

| Blind man's Buff | 13 |

| Blind Postman | 13 |

| Blowing out the Candle | 13 |

| Bouts Rimés | 14 |

| "Brother, I'm Bobbed" | 14 |

| "Buff says 'Baff'" | 14 |

| Buff with the Wand | 15 |

| Capping Verses | 15 |

| Charades | 15 |

| Clairvoyant | 17 |

| Comic Concert, The | 18 |

| Consequences | 18 |

| Conveyances | 19 |

| Crambo | 19 |

| Cross Questions and Crooked Answers | 20 |

| "Cupid is Coming" | 20 |

| Cushion Dance, The | 20 |

| Definitions | 21 |

| Dumb Crambo | 21 |

| Dwarf | 21 |

| Elements, The | 22 |

| Farmyard, The | 22 |

| Feather, The | 22 |

| Finding the Ring | 22 |

| Flying | 23 |

| Forfeits | 23 |

| Giant | 28 |

| Giraffe, The | 28 |

| Grand Mufti, The | 28 |

| Hands | 28 |

| "He can do little who can't do this" | 29 |

| Hiss and Clap | 29 |

| "Hot Boiled Beans" | 29 |

| Hot Cockles | 29 |

| House Furnishers | 29 |

| "How do you like your Neighbour?" | 30 |

| "How, When, and Where?" | 30 |

| Hunt the Ring | 30 |

| Hunt the Slipper | 30 |

| Hunt the Whistle | 31 |

| "I Apprenticed my Son" | 31 |

| "I Love my Love" | 31 |

| "Jack's Alive" | 31 |

| Jolly Miller, The | 32 |

| Judge and Jury | 32 |

| Magic Answer, The | 32 |

| Magical Music | 33 |

| Magic Hats, The | 33 |

| Magic Wand, The | 33 |

| "The Minister's Cat" | 34 |

| Mixed-up Poetry | 34 |

| Musical Chair | 35 |

| "My Master has sent me unto you" | 35 |

| Nouns and Questions | 35 |

| Object Game, The | 35 |

| Old Soldier, The | 36 |

| Oranges and Lemons | 36 |

| Original Sketches | 37 |

| "Our Old Grannie doesn't like Tea" | 37 |

| Pairs | 37 |

| Person and Object | 37 |

| Pork-Butcher, The | 38 |

| Postman's Knock | 38 |

| Proverbs | 38 |

| Quaker's Meeting, The | 38 |

| Resting Wand, The | 39 |

| Retsch's Outlines | 39 |

| Reviewers, The | 40 |

| Rhymes | 40 |

| Rule of Contrary | 41 |

| Russian Gossip | 41 |

| Schoolmaster, The | 41 |

| Shadow Buff | 41 |

| Shouting Proverbs | 42 |

| "Simon says" | 42 |

| [6] Spanish Merchant, The | 42 |

| Spanish Nobleman, The | 42 |

| Spelling Bee | 43 |

| Spoon Music | 43 |

| Stage Coach, The | 44 |

| Stool of Repentance | 44 |

| Tableaux Vivants | 45 |

| Telescope Giant, The | 46 |

| Think of a Number | 46 |

| This and That | 46 |

| Throwing Light | 47 |

| Toilet | 47 |

| Trades, The | 48 |

| Traveller's Alphabet, The | 48 |

| Twenty Questions | 49 |

| Two Hats, The | 49 |

| "What am I Doing?" | 49 |

| "What is my Thought like?" | 49 |

| Who was he? | 50 |

| Wild Beast Show, The | 50 |

| "Yes or No?" | 50 |

TOY GAMES AND TOY-MAKING.

| PAGE | |

| Æolian Harp | 52 |

| Animated Serpent | 52 |

| Annulette | 53 |

| Apple Mill | 53 |

| Apple Woman | 53 |

| Bandilor | 54 |

| Battledore and Shuttlecock | 54 |

| Bell and Hammer | 54 |

| Bird Whistles | 54 |

| Birds, Beasts, and Fishes | 54 |

| Bombardment | 54 |

| Bottle Imps | 54 |

| Brother Jonathan | 55 |

| Camera (Miniature) | 55 |

| Cannonade | 55 |

| Carpet Croquet | 56 |

| Castle Bagatelle | 56 |

| Common Whistle | 56 |

| Crack Loo | 56 |

| Cup and Ball | 56 |

| Cupolette | 56 |

| Cut-water | 57 |

| Dancing Highlander | 57 |

| Dancing Pea | 57 |

| Dart and Target | 58 |

| Dartelle | 58 |

| Decimal Game | 58 |

| Demon Bottle | 58 |

| Drawing-room Archery | 59 |

| Dutch Racquets | 59 |

| Enfield Skittles | 59 |

| Flying Cones | 59 |

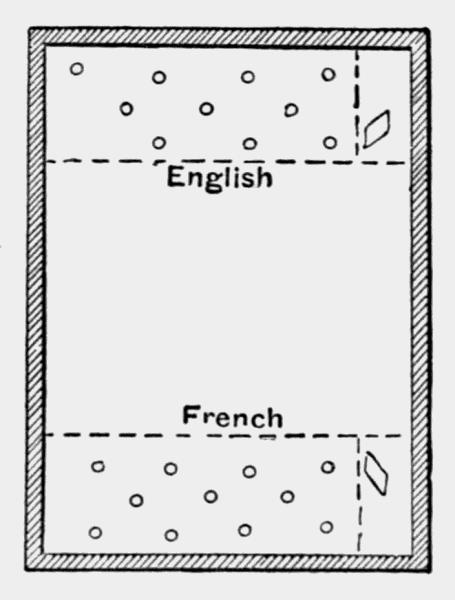

| French and English | 60 |

| Gas Balloons | 60 |

| German Balls | 60 |

| German Billiards | 61 |

| Hat Measurement | 61 |

| Homeward Bound | 61 |

| Hydraulic Dancer | 61 |

| Immovable Card | 61 |

| Indian Skittle Pool | 61 |

| Jack-in-the-Box | 62 |

| Japanese Fan | 62 |

| Jerk Straws | 62 |

| Le Diable | 62 |

| Magic Fan | 62 |

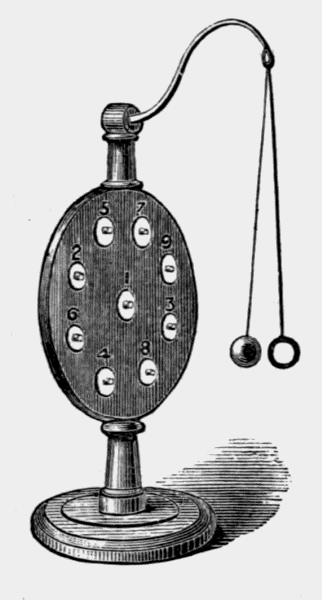

| Magic Figure | 64 |

| Magic Flute | 64 |

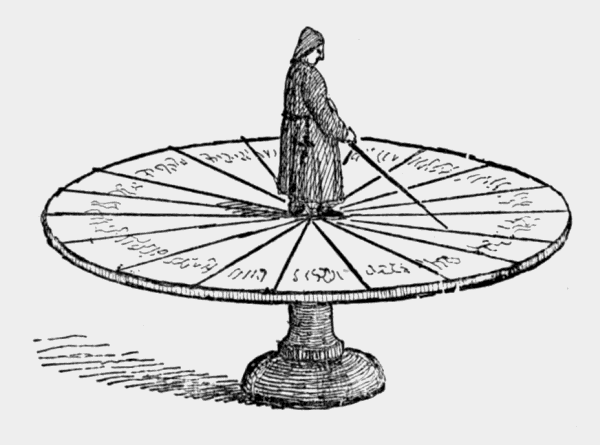

| Magician of Morocco | 64 |

| Magnetic Swan | 65 |

| Magnetic Wand | 65 |

| Magnifying Pinhole | 66 |

| Mechanical Bucephalus | 66 |

| Microscope (Toy) | 66 |

| Mocking Call | 67 |

| Moorish Fort | 67 |

| Navette | 67 |

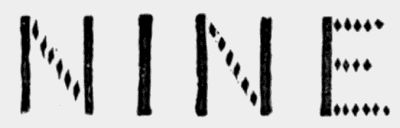

| Nine pins | 68 |

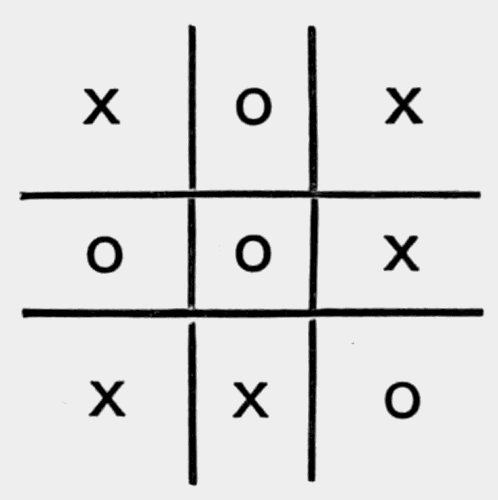

| Noughts and Crosses | 68 |

| Obedient Soldier | 68 |

| Palada | 68 |

| Paper Bellows | 69 |

| Paper Boat | 69 |

| Paper Boxes | 70 |

| Paper Chinese Junk | 70 |

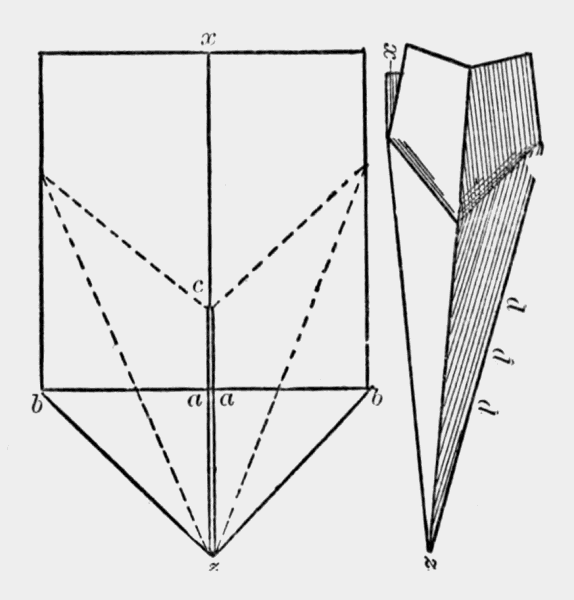

| Paper Dart | 72 |

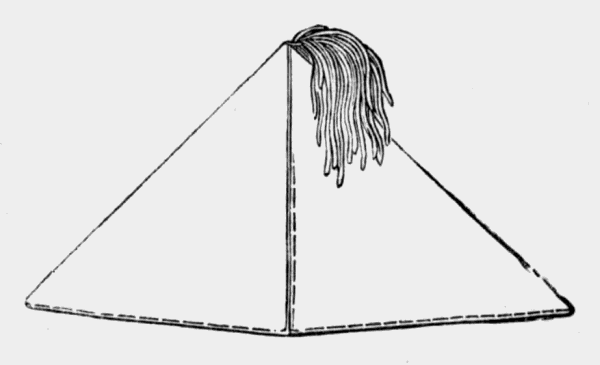

| Paper Hat (Pyramidal) | 72 |

| Paper Parachute | 72 |

| Paper Purses | 73 |

| Parlour Bowls | 74 |

| Parlour Croquet | 74 |

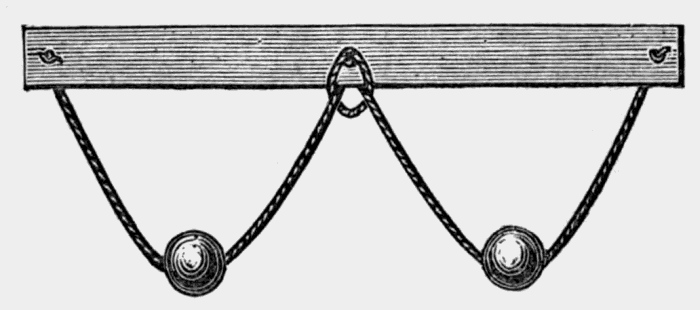

| Parlour Quoits | 74 |

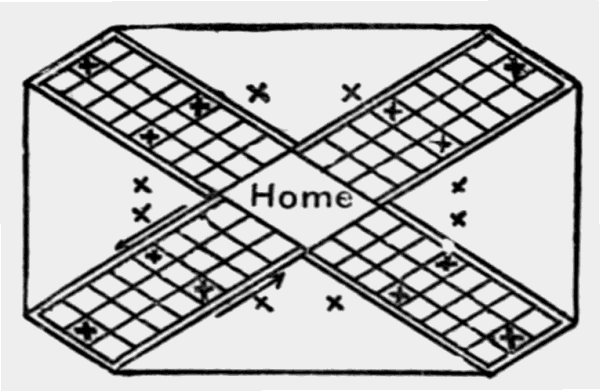

| Patchesi; or, Homeward Bound | 75 |

| Pegasus in Flight | 75 |

| Pith Dancer | 76 |

| Prancing Horse | 76 |

| Prophet | 76 |

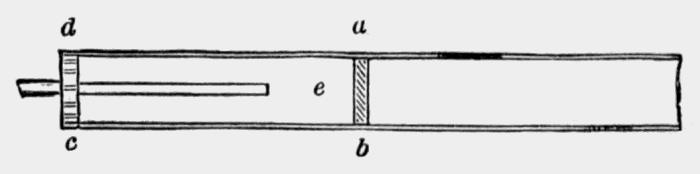

| Puff and Dart | 77 |

| Push Pin | 78 |

| Puzzle-wit | 78 |

| Quintain | 78 |

| Quiz | 78 |

| Race Game | 78 |

| Racquets (Drawing-Room) | 79 |

| Revolving Ring | 79 |

| [7]Ringolette | 80 |

| Ring the Bull | 80 |

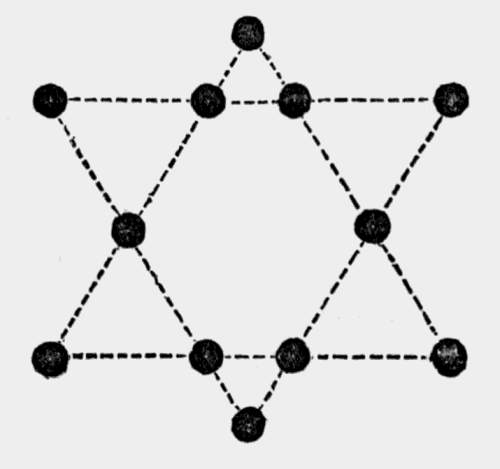

| Royal Star | 80 |

| Schimmel | 81 |

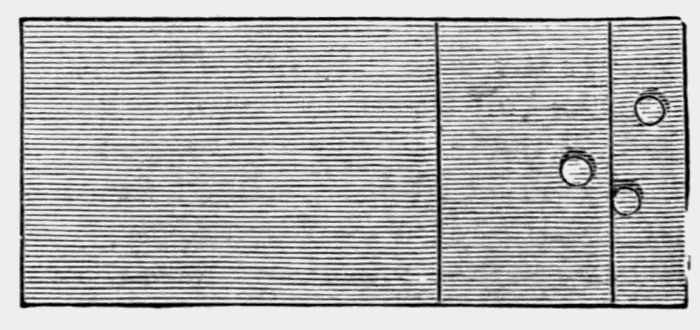

| Shovel Board | 82 |

| Skittle Cannonade | 83 |

| Slate Games | 84 |

| Spillikins or Spelicans | 85 |

| Squails | 86 |

| Squeaker | 86 |

| Steady Tar | 87 |

| Summer Ice | 87 |

| Sybil | 87 |

| Table Croquet | 87 |

| Targetta | 87 |

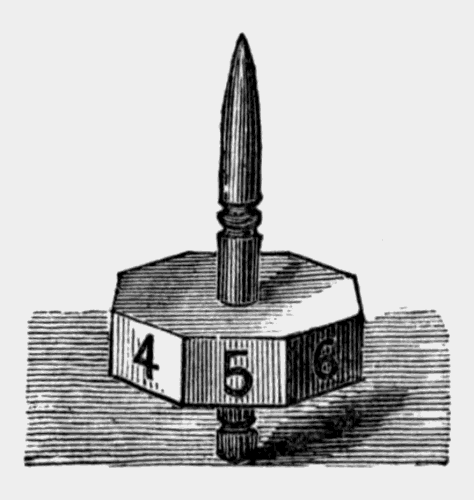

| Teetotum | 88 |

| Tit-tat-to | 88 |

| Tournament | 88 |

| Trails | 88 |

| Trouble Wit | 88 |

| Wonderful Trumpet | 88 |

MECHANICAL PUZZLES.

| PAGE | |

| Balanced Pail, The | 90 |

| Balanced Stick, The | 90 |

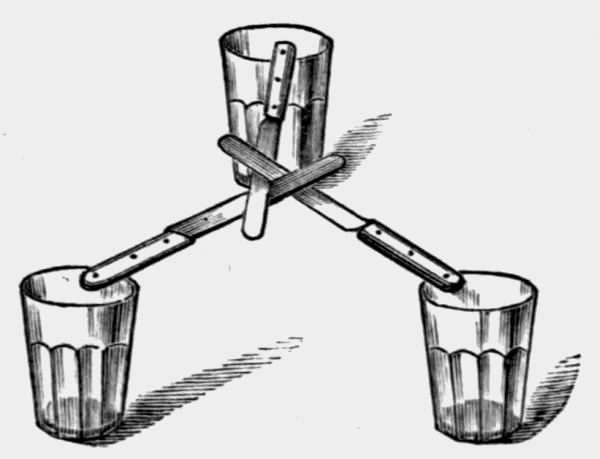

| Bridge of Knives, The | 91 |

| Square and Circle Puzzle, The | 91 |

| Carpenter's Puzzle, The | 91 |

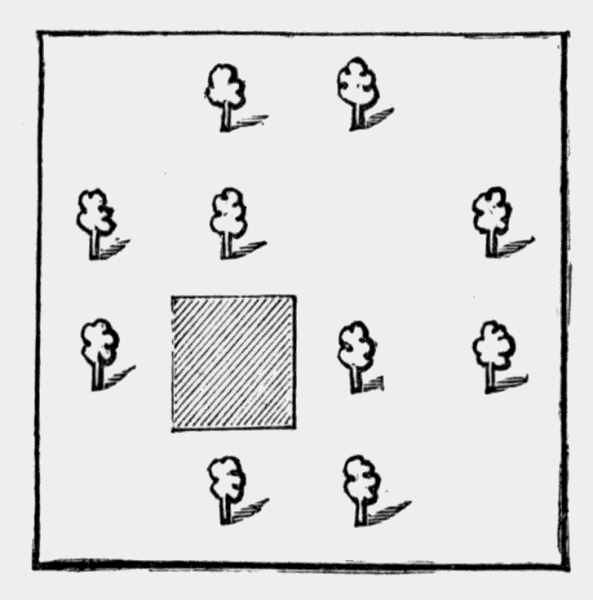

| Divided Farm, The | 92 |

| Vertical Line Puzzle, The | 92 |

| String and Balls Puzzle, The | 92 |

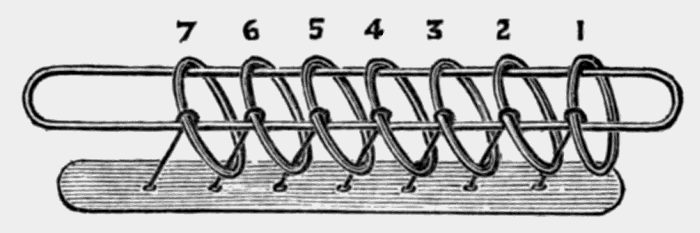

| Puzzling Rings, The | 93 |

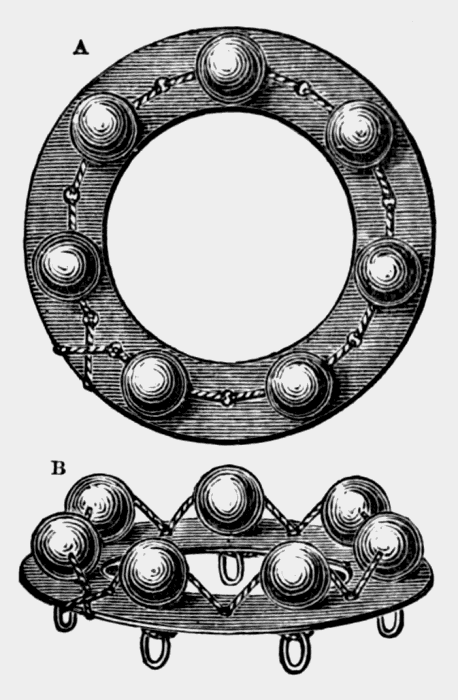

| Balls and Rings Puzzle, The | 93 |

| Staff Puzzle, The | 94 |

| Victoria Puzzle, The | 94 |

| Artillery Puzzle, The | 94 |

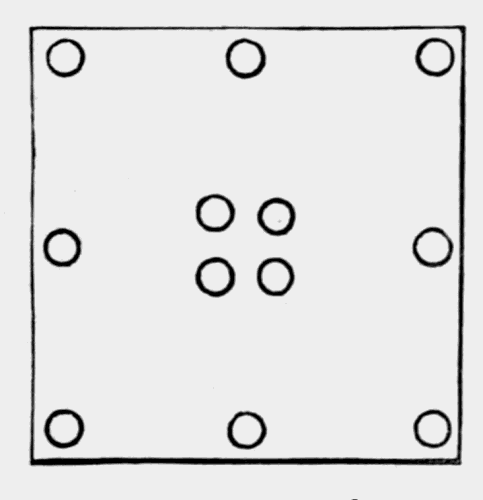

| Six Rows Puzzle, The | 94 |

| Six-Square Puzzle, The | 94 |

| Magic Octagon, The | 94 |

| Accommodating Square, The | 94 |

| Magic Cross, The | 95 |

| To Take a Man's Waistcoat off without Removing his Coat | 95 |

| To Break a Stone with a Blow of the Fist | 96 |

| The Key, the Heart, and the Dart | 96 |

| Prisoners' Release Puzzle, The | 96 |

| Hampton Court Maze | 96 |

ARITHMETICAL PUZZLES.

| PAGE | |

| American Puzzles, "15" and "34" | 97 |

| Magic Nine, The; or, Puzzle of Fifteen, The | 98 |

| Magic Thirty-six, The; or, Puzzle of One Hundred and Eleven, The | 98 |

| Magic Hundred, The; or, Puzzle of Five Hundred and Five, The | 99 |

| Twenty-four Monks, The | 99 |

| To take One from Nineteen so that the Remainder shall be Twenty | 100 |

| Famous Forty-five, The | 100 |

| Costermonger's Puzzle, The | 100 |

| Progression of Numbers, The | 101 |

| How a Number thought of or otherwise indicated may be told | 102 |

| Magical Addition | 103 |

| Clever Lawyer, The | 104 |

| A New Way of Multiplying by 9 | 104 |

| To Reward the Favourites and Show no Favouritism | 105 |

| Dishonest Servants, The | 105 |

| Lord Dundreary's Finger Puzzle | 105 |

| Uniform Results of Multiplication | 105 |

| To Ascertain a Square Number at a Glance | 106 |

| To Distinguish Coins by Arithmetical Calculation | 106 |

| Properties of Numbers | 106 |

CARD GAMES.

| PAGE | |

| Long Whist | 107 |

| Short Whist | 115 |

| Piquet | 116 |

| Euchre | 118 |

| Vingt-un | 120 |

| Speculation | 121 |

| Napoleon | 122 |

| Cribbage | 122 |

| Ranter go Round | 125 |

| Écarté | 126 |

| Loo | 128 |

| Cassino | 129 |

| Put | 131 |

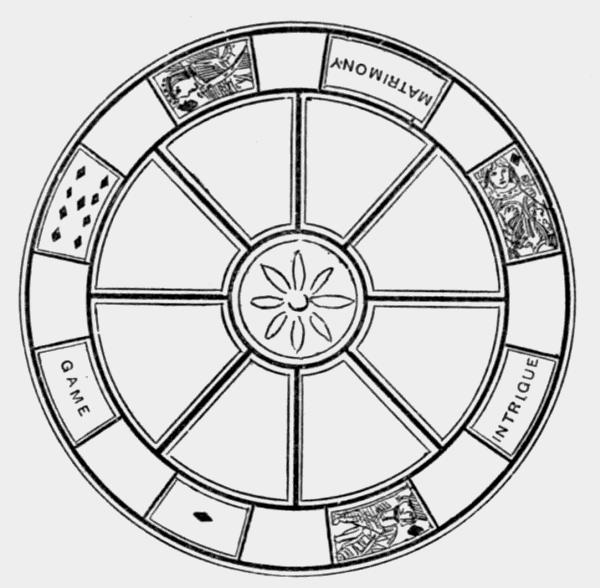

| [8]Matrimony | 131 |

| All Fours | 132 |

| Poker | 134 |

| Snip-Snap-Snorum | 136 |

| Commerce | 137 |

| Sift Smoke | 138 |

| Lottery | 138 |

| Quince | 139 |

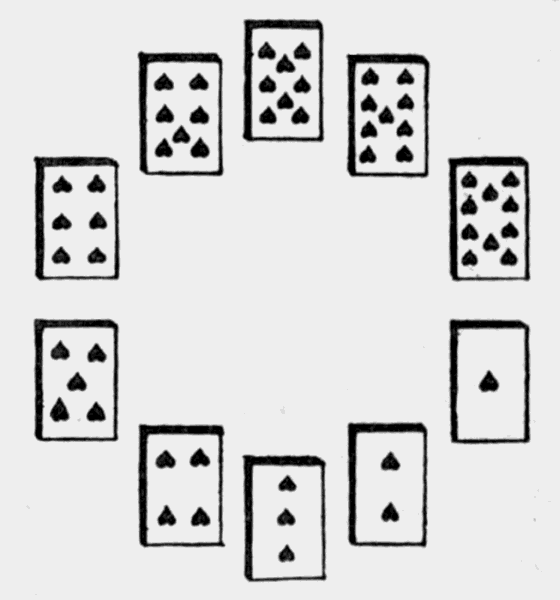

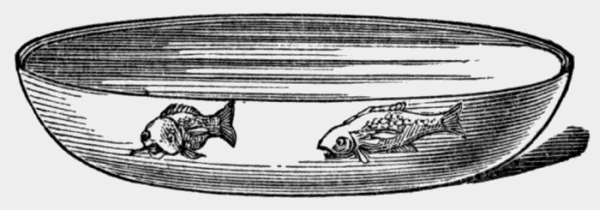

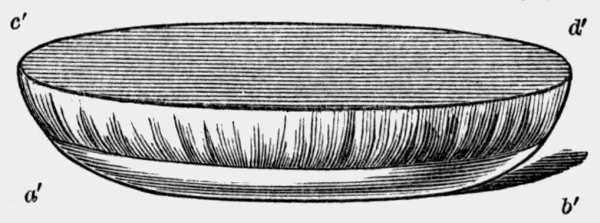

| Pope Joan | 139 |

| Spinado | 140 |

| Old Maid | 141 |

| Spade and Gardener | 142 |

| Happy Families | 142 |

| Bézique | 143 |

| Snap | 144 |

| Zetema | 145 |

| French Vingt-un, or Albert Smith | 148 |

| Beggar my Neighbour | 149 |

| Catch the Ten | 149 |

| Cheat | 150 |

| Truth | 150 |

PARLOUR MAGIC.

| PAGE | |

| Conjuring | 151 |

| Simple Deceptions and Minor Tricks | 152 |

| Card Tricks and Combinations | 153 |

| Conjuring with and without Special Apparatus | 167 |

| Clairvoyance or Second Sight | 178 |

| Ventriloquism and Polyphony | 180 |

FIRESIDE FUN.

| PAGE | |

| Decapitations | 185 |

| Curtailments and Retailings | 186 |

| Anagrams | 189 |

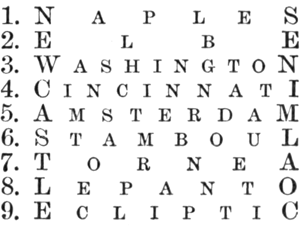

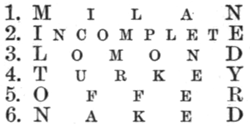

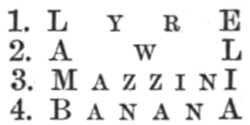

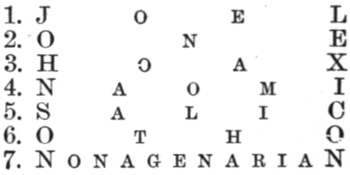

| Word Squares | 191 |

| Birds, Fruits, and Flowers Enigmatically Expressed | 192 |

| Rebuses | 193 |

| Arithmorems | 194 |

| Diamond Puzzles and Word Puzzles of Various Shapes | 196 |

| Cryptography | 197 |

| Chronograms | 198 |

| Logograms | 200 |

| Metagrams | 202 |

| Word Capping | 203 |

| Paragrams | 203 |

| Extractions | 204 |

| Transpositions | 204 |

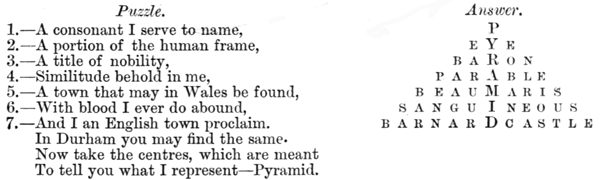

| Definitions | 205 |

| Inversions | 206 |

| Hidden Words | 206 |

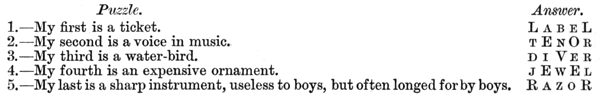

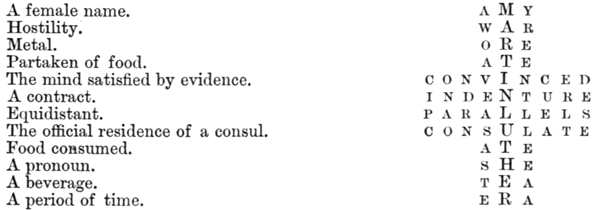

| Numbered Charades | 208 |

| Letter and Figure Charades | 210 |

| Verbal Charades | 211 |

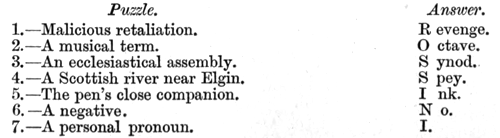

| Acrostics | 211 |

| Enigmas | 213 |

| Alphabetical Puzzles | 215 |

| Guessing Stories | 216 |

| Mental Scenes | 217 |

CASSELL'S

Book of In-door Amusements.

It is certainly a matter of regret that the names of most of the good people to whom we are indebted for the introduction of our favourite old-fashioned Round Games are buried in obscurity, for they deserve, in our estimation at least, the name of benefactors quite as much as any great discoverer or inventor. What higher aim could they possibly have had in view than that of teaching people how to enjoy themselves? It has been said that in the world there are two great heaps, one of human happiness, and the other of human misery, and that we are all engaged the whole day through in taking a portion from one heap and carrying it to the other. Surely the portion carried from one heap to the other by the kind folk who have at various times furnished us with our amusements must by this time be one of considerable size, and in spite of their names being unknown to us, we will ever feel grateful to them for contributing so largely to our enjoyment of life. A long time ago it was observed of the English as a race that they took their pleasures sadly; but we will hope that henceforth the observation may be applicable to past generations only, and that our readers at any rate will resolve that when they play they will play heartily, just as when they work they will work heartily. To the really hearty players, therefore, we have great pleasure in handing our collection of Round Games.

In this game each player may take a part, or if thought preferable, the company may divide themselves into actors and spectators. The actors then each fix upon a proverb which is to be represented by every one of them individually. There is to be no connection between them in any way. Each one in turn has simply to act before the rest of the company the proverb he has selected. The first player might, for instance, come into the room holding a cup in his hand; then, by way of acting his proverb, he might repeatedly make an appearance of attempting to drink out of the cup, but of being prevented each time by the cup slipping out of his hands, thus in dumb show illustrating the proverb, "There's many a slip between the cup and the lip." The second might come into the room rolling a ball, a footstool, or anything else that would do to represent a stone. After rolling it about for some time he takes it up and examines it with astonishment, as if something were wanting that he expected to find on it, making it, perhaps, too plainly evident to the company that the proverb he is aiming to depict is the familiar one of "A rolling stone gathers no moss." If really good acting be thrown into this game, it may be made exceedingly interesting.

A word is chosen by the company which is likely to have a good many other words rhyming with it.

The first player then begins by silently acting some word that will rhyme with the one chosen; as for instance, should the selected word be flow, the first[10] actor might imitate an archer, and pretend to be shooting with a bow and arrow, thus representing the word bow, or he might with an imaginary scythe cut the long grass (mow), or pretend to be on the water in a boat, and make use of imaginary oars (row). As each word is acted it should be guessed by the spectators before the next one is attempted.

A sheet of paper and a pencil are given to the players, upon which each is requested to write five or six adjectives. In the meantime one of the company undertakes to improvise a little story, or, which will do quite as well, is provided with some short narrative from a book.

The papers are then collected, and the story is read aloud, the reader of the same substituting for the original adjectives those supplied by the company on their papers, placing them, without any regard to sense, in the order in which they have been received.

The result will be something of this kind:—"The sweet heron is a bird of a hard shape, with a transparent head and an agitated bill set upon a hopeful neck. Its picturesque legs are put far back in its body, the feet and claws are false, and the tail very new-fangled. It is a durable distorted bird, unsophisticated in its movements, with a blind voice, and tender in its habits. In the mysterious days of falconry the places where the heron bred were counted almost shy, the bird was held to be serious game, and slight statutes were enacted for its preservation," and so on.

The great advantage to be derived from many of our most popular games is that they combine instruction with amusement. The game we are about to describe is one of this number, and will give the players the opportunity of exhibiting their geographical knowledge, as well as any knowledge they may have as to the physical condition, manufactures, and customs of the countries which, in imagination, they intend visiting.

The company must first of all fancy themselves to be a party of travellers bound for foreign lands.

A starting-place is fixed upon, from which point the first player sets out on his journey. In some cases maps are allowed, and certainly, if any one should be doubtful as to the accuracy of his ideas of locality, both for his own sake and that of his friends he will do wisely to have a map before him.

The first player then proceeds to inform the company what spot he means to visit, and what kind of conveyance he means to travel in; on arriving at the place what he means to buy, and on returning home which of his friends is to be favoured by having his purchase offered as a gift.

To do all this is not quite so easy as might at first be imagined. In the first place there must be some knowledge of the country to which the traveller is going; he must know the modes of conveyance, the preparations he will have to make, and the time that will be occupied during the journey.

Also, he must know something of the capabilities of the people whom he means to visit, because what he buys must be something that is manufactured by them, or that is an article of produce in their country. For instance, he must not go to North America for grapes, or to the warm and sunny South for furs. The presents, too, must be suitable for the persons to whom they are to be offered. A Japanese fan must not be offered to a wild schoolboy, or a meerschaum pipe to a young lady. Forfeits may be exacted for any mistakes of this kind, or, indeed, for mistakes of any description; the greater will be the fun if at the end of the game a good number of forfeits should have accumulated.

The second player must make his starting-point where his predecessor completed his travels, and may either cut across the country quickly, make his purchase, and return home again, or he may loiter on the road to sketch, botanise, or amuse himself in any other way.

It is astonishing how much pleasure may be derived by listening to the various experiences related, especially when a few of the company are gifted with vivid imaginations.

Sometimes rhyme is employed instead of prose for recounting the travels, and with very great success. When this is done the speaker may, if so inclined, end his description abruptly, thus leaving it to the next player about to commence his narrative to supply a line which shall rhyme with the one just uttered.

This being a game of mystery, it is, of course, necessary that it should be unknown to, at any rate, a few of the company—the more the better. One of the gentlemen well acquainted with the game undertakes to represent Æsop. In order to do so more effectually, he may put a cushion or pillow under his coat to imitate a hump, provide himself with a thick stick for a crutch, make a false nose, and put a patch over one eye. The rest of the company must then each assume the name of some subject of the animal kingdom—a bird, beast, or fish—and having done this must prepare themselves to listen to the words of their great master. Limping into their midst, Æsop then tells them that the wrath of the great god Jupiter has been aroused, and as the cause of a calamity so terrible must be that one or more of them have been committing some crime or other, he is anxious to discover without further delay who are the guilty subjects. "I shall therefore," continues he, "question you closely all round, and I shall expect you every one to give me truthful answers. To begin with you, Mr. Lion, as you are the king of beasts, I sincerely hope you have done nothing derogatory to your high position; still, as it is absolutely necessary that you should be examined with the rest of your friends, will you please tell me what food you have eaten lately?" Should the lion have eaten a lamb, a sheep, a tiger, a bear, or any other dainty that is spelt without the letter O, he is acquitted as innocent; but should he have eaten a leopard, a goose, a fox, or any other creature, in the name of which the letter O occurs, he is pronounced by Æsop to be deserving of punishment, and is therefore sentenced to pay a forfeit. The other animals in turn then undergo a similar examination, during which each one must remember that in naming their prey they must confine themselves to such food as is suited to the species they have adopted. The game may be carried on for any length of time, or until all have discovered the secret in it. There is no fear of the interest flagging, so long as even only one of the company is still left unable to solve the mystery.

Provided with a good boxful of letters, either on wood or cardboard, a clean table, a bright fire, and three or four pleasant companions, I have no hesitation in saying that a very pleasant hour may be spent. It is almost needless to give directions how to proceed with the letters, for they can be used in a variety of ways, according to inclination. Sometimes a word is formed by one person, the letters of which he passes on to his neighbour, asking him to find out what the word is. A still more interesting method is for the whole party to fix upon one long word, and all try in a certain time how many different words can be made of it. Or another way, even better still, is to shuffle the letters well together, and then to give to each person a certain number. All must then make a[12] sentence out of the letters, whether with or without sense, as best they can. The transposition of words, too, is very amusing, and can be done either with the loose letters or with pencil and paper.

The names of poets, authors, or great men famous in history may be given, the letters of which may be so completely altered as to form words or sentences totally different from the original.

For instance:—

| We lads get on. | W. E. Gladstone. |

| Rich able man. | Chamberlain. |

| Side Rail. | Disraeli. |

| Pale Noon. | Napoleon. |

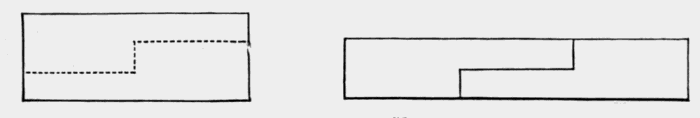

A pencil and a piece of paper of moderately good size are given to the players, each of whom is requested to draw on the top of the sheet a head of some description, it may be a human head or that of any animal, either bird, beast, or fish. As soon as each sketch is finished the paper must be folded back, and passed to the left-hand neighbour, no one on any account looking at the drawing under the fold. The body of something must next be drawn. As before, it may be either a human body or that of any animal, and the papers must then be again folded and passed to the left. Lastly, a pair of legs must be added, or it may be four legs, the number will depend upon the animal depicted. The productions all being complete, they are opened and passed round to the company, who will be edified by seeing before them some very ridiculous specimens of art—see our illustrations, for instance. The dotted lines in these figures show where the paper was folded back, as each "artist" finished his work.

A very good imitation of a Baby Elephant can easily be got up by two or three of the company, who are willing to spend a little time and trouble in making the necessary preparations. In the first place a large grey shawl or rug must be found, as closely resembling the colour of an elephant as possible. On this a couple of flaps of the same material must be sewn, to represent the ears, and also two pieces of marked paper for the eyes. No difficulty will be found in finding tusks, which may consist of cardboard or stiff white paper, rolled up tightly, while the trunk may be made of a piece of grey flannel also rolled up. The body of the dear little creature is then constructed by means of two performers, who stand one behind the other, each with his body bent down, so as to make the backs of both one long surface, the one in front holding the trunk, while the one behind holds the tusks one in each hand. The shawl is then thrown[13] over them both, when the result will be a figure very much resembling a little elephant. When all is complete, the services of a third performer should be enlisted to undertake the post of keeper to the elephant. If the person chosen for this capacity have great inventive faculties, the description given by him may be made to add greatly to the amusement of the scene.

One of the party is chosen to be the bird-catcher. The rest fix upon some particular bird whose voice they can imitate when called upon, the owl being the only bird forbidden to be chosen. Then sitting in order round the room with their hands on their knees, they listen to the story their master has to tell them. The Bird-catcher begins by relating some incident in which the feathered tribe take a very prominent position, but particularly those birds represented by the company. Each one, as the name of the bird he has chosen is mentioned, utters the cry peculiar to it, never for a moment moving his hands from his knees. Should the owl be referred to, however, every one is expected to place his hands behind him, and to keep them there until the name of another bird has been mentioned, when he must, as before, place them on his knees. During the moving of the hands, if the Bird-catcher can succeed in securing a hand, the owner of it must pay a forfeit, and also change places with the Bird-catcher.

We must not forget to observe that when the leader, or Bird-catcher, as he is called, refers in his narrative to "all the birds in the air," all the players are to utter at the same time the cries of the different birds they represent.

A handkerchief must be tied over the eyes of some one of the party who has volunteered to be blind man; after which he is turned round three times, then let loose to catch any one he can. As soon as he has succeeded in laying hold of one of his friends, if able to say who it is he is liberated, and the handkerchief is transferred to the eyes of the newly-made captive, who in his turn becomes blind man. This position the new victim must hold until, like his predecessor, he shall succeed in catching some one, and naming correctly the person he has caught.

In this game the first thing to be done is to appoint a postmaster-general and a postman. The table must then be pushed on one side, so that when the company have arranged themselves round the room there may be plenty of room to move about. The postmaster-general, with paper and pencil in hand, then goes round the room, and writes down each person's name, linking with it the name of the town that the owner of the name chooses to represent. As soon as the towns are chosen, and all are in readiness, the postman is blindfolded and placed in the middle of the room. The postmaster then announces that a letter has been sent from one town to another, perhaps from London to Edinburgh. If so, the representatives of these two cities must stand up, and, as silently as possible, change seats. While the transition is being made, the postman is at liberty to secure one of the seats for himself. If he can do so, then the former occupant of the chair must submit to be blindfolded, and take upon himself the office of postman.

No end of merriment has frequently been created by this simple, innocent game. It is equally interesting to old people and to little children, for in many cases those who have prided themselves on the accuracy of their calculating powers[14] and the clearness of their mental vision have found themselves utterly defeated in it. A lighted candle must be placed on a small table at one end of the room, with plenty of walking space left clear in front of it. One of the company is invited to blow out the flame blindfold. Should any one volunteer, he is placed exactly in front of the candle, while the bandage is being fastened on his eyes, and told to take three steps back, turn round three steps, then take three steps forward and blow out the light. No directions could sound more simple. The opinion that there is nothing in it has often been expressed by those who have never seen the thing done. Not many people, however, are able to manage it—the reason why, you young people will soon find out, if you decide to give the game a fair trial.

Several rhyming games are given among these Round Games, and the following is simply a variety of some of them:—

A slip of paper is given to each player, who is requested to write in one corner of it two words that rhyme.

The papers are then collected and read aloud, after which every one is expected to write a short stanza, introducing all the rhymes that, have been suggested.

When the completed poems are read aloud, it is very amusing to observe how totally different are the styles adopted by the various authors, and how great is the dissimilarity that exists between the ideas suggested by each one.

Two chairs are placed in the middle of the room, upon one of which some one unacquainted with the game must be asked to take a seat. The other chair must be occupied by a lady or gentleman to whom the game is familiar. A large shawl or tablecloth is then put over the heads of both, so that nothing that is going on in the room can be visible to them. The person, however, who understands the game may stealthily pull away the cloth from his own head, keeping it round his shoulders only, so that his companion may have no suspicion that both are not equally blindfolded. The player acquainted with the game then with his slipper hits his own head, at the same time calling out, "Brother, I'm bobbed." His blind companion will then ask, "Who bobbed you?" upon which the first player must name some person in the room, as if making a guess in the matter. He will next hit the head of the player under the shawl with the slipper, who will also exclaim, "Brother, I'm bobbed." "Who bobbed you?" the first player will inquire. The blinded player may then guess which person in the room he suspects of having hit him. The fun of the whole affair lies in the fact that the bobbing, which the blind player suspects is performed by the various members of the company, is really chiefly done by the player sitting close beside him. Sometimes, too, the bobbing business is done so effectually, and with such force, as to render it anything but amusing to the poor blinded victim, although to the spectators it may be unmistakably so. Should the victim be a gentleman, a few sharp raps with a slipper will not make any material difference to him; but if instead it should happen to be a lady, the "bobbing" must be of the gentlest.

In this game no one is allowed to either laugh or smile; consequently, it is generally one of the games chosen when the merriment of the evening has reached its highest pitch. The company seat themselves in a half circle at one end of the room, with the exception of one of their number, who is supposed to have gone on a visit to Buff. He then enters the room with the poker in his[15] hand, and his face looking as grave as possible. When he is asked by his friends in succession:—

"Where do you come from?"

"From Buff."

"Did he say anything to you?"

"Buff said Baff,

And gave me this staff,

Telling me neither to smile nor laugh.

Buff says Baff to all his men,

And I say Baff to you again,

And he neither laughs nor smiles,

In spite of all your cunning wiles,

But carries his face with a very good grace,

And passes his stick to the very next place."

If all this can be repeated without laughing, the player is highly to be commended. He may then deliver up his staff to some one else, and take his seat.

Blind Man's Buff is so time-honoured and popular with young and old, that one would think it impossible to devise a better game of the kind. The newer game of Buff with the Wand, however, is thought by many to be superior to the long-established favourite. The blinded person, with a stick in his hand, is placed in the middle of the room. The remainder of the party form a ring by joining hands, and to the music of a merry tune which should be played on the piano they all dance round him. Occasionally the music should be made to stop suddenly, when the blind man takes the opportunity of lowering his wand upon one of the circle. The person thus made the victim is then required to take hold of the stick until his fate is decided. The blind man then makes any absurd noise he likes, either the cry of animals, or street cries, which the captured person must imitate, trying as much as possible to disguise his own natural voice. Should the blind man detect who holds the stick, and guess rightly, he is released from his post, the person who has been caught taking his place. If not, he must still keep the bandage on his eyes, and hope for better success next time.

This game is not unlike one that is elsewhere described as "Mixed-up Poetry." Every one at the table is supplied with a sheet of paper and a pencil, at the top of which is written by each player a line of poetry either original or from memory. The paper must then be folded down so as to conceal what has been written, and passed on to the right; at the same time the neighbour to whom it is passed must be told what is the last word written in the concealed line. Every one must then write under the folded paper a line to rhyme with the line above, being ignorant, of course, of what it is. Thus the game is carried on, until the papers have gone once or twice round the circle, when they can be opened and read aloud.

Although the acting of charades is by no means an amusement of very recent invention, it is one that may always be made so thoroughly attractive, according to the amount of originality displayed, that most young people, during an evening's entertainment, hail with glee the announcement that a charade is about to be acted. It is not necessary that anything great should be attempted in the way of dressing, scenery, or similar preparations, such as are almost indispensable to the performance of private theatricals. Nothing is needed beyond a[16] few old clothes, shawls, and hats, and a few good actors, or rather, a few clever, bright, intelligent young people, all willing to employ their best energies in contributing to the amusement of their friends. What ability they may possess as actors will soon become evident by the success or failure of the charade.

The word charade derives its name from the Italian word Schiarare—to unravel or to clear up. Suitable as the word may be in some instances, we cannot help thinking that in the majority of cases the acting of a charade has the effect of making the word chosen anything but clear; indeed, the object of the players generally is to make it as ambiguous as possible. As all players of round games know how charades are got up, it would be superfluous to give any elaborate instructions regarding them, though perhaps the following illustration may be useful.

Scene 1.—In which the word Go is to be introduced.

The curtain drawn aside. Miss Jenkyns is seen reclining on her drawing-room couch, with a weary look on her face and a book in her hand.

Enter Footman.

Footman (pulling his forelock).—"Please ma'am, I'm come to say I wish to give you notice; I can't stop here no longer!"

Lady.—"Why, James, how is this? What can have made you so unexpectedly come to this decision?"

James.—"Well, ma'am, you see I want to live where there are more carriage visitors. I have nothing at all to say against you, ma'am, or the place; but I want to better myself by seeing a little of 'igh life."

Lady.—"Then if you have no other reason for wanting to go, James, I fear we shall have to part, as I certainly can't arrange to receive carriage visitors simply for your benefit." (Sinks languidly back on the couch and resumes her book. James retires.)

Lady (to herself).—"How tiresome these servants are, to be sure, now I shall have the trouble of engaging a new footman. I really think no one with my delicate health had ever so much to do before." (Rises and retires.)

Scene 2.—Bringing in the word Bang.

Old gentleman sitting in an arm-chair, a table by his side, on which medicine bottles and a gruel basin are placed, and his leg, thickly bandaged, resting on a chair.

Old Gent.—"Oh, this horrid pain! what shall I do? will no one come to help me? That stupid doctor has done me no good."

Enter Maid-servant.—"Please, sir, the doctor has come. Shall I tell him to come upstairs?"

Old Gent.—"Of course you must, and unless he is quick I shall die before he gets here. Oh dear! Oh dear!" (Exit maid, banging the door after her.)

Old Gent (shrieking out with pain).—"Oh, you cruel creature, how can you bang the door in that way, when even the slightest footstep on the floor is enough to make me wild? Quick, doctor, quick!" (Here the maid again appears, holding the door open for the doctor.)

Doctor (with a large case of instruments under his arm).—"Mr. Grumbleton, you appear to be very ill; can I do anything to relieve you? Let me feel your pulse."

Old Gent.—"Oh, my leg!"

Doctor.—"Your nerves are in a very excited state; you must have perfect quiet." (Here the street door is heard to bang loudly, making the house shake.)

Old Gent.—"Keep quiet, do you say! You might as well tell me to cut my leg off. There is no such thing as quiet in this house. That little good-for-nothing of a maid never comes into the room without shutting the door with a bang."

Doctor.—"Be calm, my dear friend, and I will order you a soothing mixture, and as I leave the house I will insist upon perfect quiet being maintained." (Then rebandaging the gentleman's leg, and placing him comfortably in the arm-chair, the doctor retires.)

Scene 3.—Bringing in the whole word, Go-bang.

Inside a coffee-room. Two or three friends are seated with their coffee and pipes, when one, who has just returned from foreign lands, begins relating some of his adventures.

Smith.—"Yes, my boys, glad as I am to get back to my own country, I should not like to be without the remembrance of all that I have witnessed in the far-off lands I have been visiting."

Brown.—"Yes, friend, you must have had a brave heart to face the thousand dangers to which no doubt you have been exposed. But though it's getting late, we must, before parting, hear one of your adventures. So proceed, comrade."

Smith.—"Well, it's not worth while beginning a long tale when there's not time to finish it, so I'll just sketch the sort of risk one often runs in the wilds of the backwoods. My mates and I had been out one day on a hunting expedition, when, returning home late at night, I unfortunately got left behind. The darkness was so great that my absence was not noticed, and before very long I found I had taken the wrong track. I came to this conclusion because I heard nothing but the tramp of my own horse's hoofs, when suddenly I felt that danger was at hand. Almost before I could put my thoughts into words, I felt something go bang close past my ear; then three Indians rushed upon me. Instead of feeling fear, a kind of supernatural strength took possession of me. I lifted my pistol and shot the man nearest to me, the next I felled; when, strange to say, the third man just at this moment turned round and fled. I suppose he heard the voices and footsteps of my friends, who were, at last, coming in search of me. At any rate he disappeared, when we all made the best of our way home, truly thankful that my life had been spared."

Jones.—"Well done, Smith! Next time we meet you must tell us of the many escapes you have had, and wonderful scenes you have witnessed in foreign parts."

The following, among other words, are suitable for charade acting:—

Adulation, Andrew, Arrowroot, Artichoke, Articulate; Bayonet, Bellman, Bondmaid, Bonfire, Bookworm, Bracelet, Bridewell, Brimstone, Brushwood; Cabin, Carpet, Castaway, Catacomb, Champaign, Chaplain, Checkmate, Childhood, Cowslip, Cupboard, Cutlet; Daybreak, Dovetail, Downfall, Dustman; Earrings, Earshot, Exciseman; Farewell, Footman; Grandchild; Harebell, Handiwork, Handsome, Hardship, Helpless, Highgate, Highwayman, Homesick, Hornbook; Illwill, Indigent, Indulgent, Inmate, Insight, Intent, Intimate; Jewel, Jonquil, Joyful; Kindred, Kneedeep; Label, Lawful, Leapyear, Lifelike, Loophole, Loveknot; Madcap, Matchless, Milkmaid, Mistake, Misunderstand, Mohair, Moment, Moonstruck; Namesake, Necklace, Nightmare, Nightshade, Ninepin, Nutmeg; Orphanage, Outside, Oxeye; Padlock, Painful, Parsonage, Penmanship, Pilgrim, Pilot, Pinchbeck, Purchase; Quarto, Quicklime, Quicksand, Quickset, Quicksilver; Ragamuffin, Ringleader, Roundhead, Ruthful; Scarlet, Season, Sentinel, Sightless, Skipjack, Sluggard, Sofa, Solo, Somebody, Sonnet, Sparerib, Sparkling, Spectacle, Speculate, Speedwell, Spinster, Starling, Statement, Stucco, Supplicate, Sweetmeat, Sweetheart; Tactic, Tartar, Tenant, Tendon, Tenor, Threshold, Ticktack, Tiresome, Toadstool, Token, Torment, Tractable, Triplet, Tunnel; Upright, Uproar; Vampire, Vanguard; Waistcoat, Watchful, Watchman, Waterfall, Wayward, Wedding, Wedlock, Welcome, Welfare, Wilful, Willow, Workmanship; Yokemate, Youthful.

In this game one of the company standing outside the room is, strange to say, able to describe what is passing inside. A dialogue such as would have to be carried on between the principal players will best describe the game, and show how it is to be played:—

"Do you quite remember how the room is furnished in which we are sitting?"

"I do."

"Do you remember the colour of the chairs?"

"I do."

"Do you know the ornaments on the mantelpiece?"

"I do."

"And the vase of flowers?"

"I do."

"The old china in the cabinet?"

"Yes."

"The stuffed birds?"

"Yes."

"You think there is nothing in the room that has escaped your notice?"

"Nothing."

"Then please tell me which article I am now touching."

"You are touching the vase of flowers."

The vase of flowers being the only object preceded by the word and, the clairvoyant knows that that is the object which will be touched. The fun of the game, of course, consists in puzzling those of the company to whom the secret is unknown.

In this performance the company for the time imagine themselves to be a band of musicians. The leader of the band is supposed to furnish each of the performers with a different musical instrument. Consequently, a violin, a harp, a flute, an accordion, a piano, a jew's-harp, and anything else that would add to the noise, are all to be performed upon at the same time. Provided with an instrument of some description himself, the leader begins playing a tune on his imaginary violoncello, or whatever else it may be, imitating the real sound as well as he can both in action and voice. The others all do the same, the sight presented being, as may well be imagined, exceedingly ludicrous, and the noise almost deafening. In the midst of it, the leader quite unexpectedly stops playing, and makes an entire change in his attitude and tone of voice, substituting for his own instrument one belonging to some one else. As soon as he does this, the performer who has been thus unceremoniously deprived of his instrument takes that of his leader, and performs on it instead. Thus the game is continued, every one being expected to carefully watch the leader's actions, and to be prepared at any time for making a sudden change.

The old-fashioned game of Consequences is so well known that there are doubtless few people who are not thoroughly acquainted with it. It is played in the following manner:—Each person is first provided with half a sheet of note paper and a lead pencil. The leader of the game then requests that (1) one or more adjectives may be written at the top of each paper by its owner, and that, having done so, the paper may be folded down about half an inch, so as to conceal what has been written. Every one then passes the paper to the right-hand neighbour, and proceeds to write on the sheet that has just been given him by his left-hand neighbour, (2) the name of a gentleman, again folding the paper down and passing it on to the right. Then (3) one or more adjectives are written; then (4) a lady's name; next (5) where they met; next (6) what he gave her; next (7) what he said to her; next (8) what she said to him; next (9) the consequences; and lastly (10) what the world said about it.

Every time anything is written the paper must be turned down and passed on to the right. As soon as every one has written what the world said the papers are collected, and the leader will edify the company by reading them all aloud. The result will be something of this kind, or perhaps something even more absurd may be produced—"The happy energetic (1) Mr. Simpkins (2) met the modest (3) Miss Robinson (4) in the Thames Tunnel (5). He gave her a sly glance (6), and said to her, 'Do you love the moon?' (7). She replied, 'Not if I know it' (8). The consequence was they sang a duet (9), and the world said, 'Wonders never cease'" (10).

To do justice to this game it will be necessary for the players to call to mind all they have ever read or heard about the various modes of travelling in all the four quarters of the globe, because every little detail will be of use.

The business commences by one of the company announcing that he intends starting on a journey, when he is asked whether he will go by sea or by land. To which quarter of the globe? Will he go north, south, east, or west? and last of all—What conveyance does he intend to use?

After these four questions have been answered, the first player is called upon to name the spot he intends to visit.

Mountain travelling may be described, the many ingenious methods of which are so well known to visitors to Italy and Switzerland.

The wonderful railway up the Righi need not be forgotten; mule travelling, arm-chairs carried by porters, and the dangerous-looking ladders which the Swiss peasants mount and remount so fearlessly at all times of the year, in order to scale the awful precipices, will each be borne in mind. In the cold regions the sledges drawn by reindeer may be employed, or the Greenland dogs, not forgetting the tremendous skates, that have the appearance of small canoes, used by the Laplanders; and also the stilts, which are used by some of the poor French people who live in the west of their country. Indeed, it is amazing how many different methods of conveyance have been contrived at one time or another for the benefit of us human beings.

In Spain and other places there are the diligences; in Arabia the camels; in China the junks; at Venice the gondolas.

Then, to come home, we have balloons, bicycles, wheelbarrows, perambulators, and all kinds of carriages, so that no one need be long in deciding what mode of travelling he shall for the time adopt. As soon as the four questions have been answered, should the first player be unable to name what country he will visit he must pay a forfeit, and the opportunity is passed on to his neighbour.

This game may be made intensely amusing, as will be proved by trial; and at the same time a very great amount of instruction may be derived from it.

Two pieces of paper, unlike both in size and colour, are given to each person. On one of them a noun must be written, and on the other a question. Two gentlemen's hats must then be called for, into one of which the nouns must be dropped, and into the other the questions, and all well shuffled. The hats must then be handed round, until each person is supplied with a question and a noun. The thing now to be done is for each player to write an answer in rhyme to the question he finds written on the one paper, bringing in the noun written on the other paper.

Sometimes the questions and the nouns are so thoroughly inapplicable to each other that it is impossible to produce anything like sensible poetry. The player need not trouble about that, however, for the more nonsensical the rhyme the greater the fun. Sometimes players are fortunate enough to draw from the hats both noun and question that may be easily linked together. A question once drawn was—"Why do summer roses fade?" The noun drawn was butterfly, so that the following rhyme was easily concocted:—

"Summer roses fade away,

The reason why I cannot say,

Unless it be because they try

To cheat the pretty butterfly."

This is a pleasant game, that may be enjoyed while sitting in a circle round the fire. The person at either end, who is honoured by commencing the game, must, in a whisper, ask a question of the player sitting next to him, taking care to remember the answer he receives, and also the question he himself asked. The second player must then do likewise, and so on, until every one in the party has asked a question and received an answer. The last person, of course, being under the necessity of receiving the answer to his question from the first person. Every one must then say aloud what was the question put to him, and what was the answer he received to the question he asked—the two together, of course, making nothing but nonsense, something like the following:—

Q. Who is your favourite author?

A. Beans and Bacon.

Q. Were you ever in love?

A. Cricket, decidedly.

Q. Are you an admirer of Oliver Cromwell?

A. Mark Twain.

Q. Why is a cow like an oyster?

A. Many a time.

Another way of playing this game is for one person to stand outside the circle; then, when all the whispering is finished, to come forward and ask a question of each person, receiving for his replies the answers they all had given to the questions they asked each other. Or what is, perhaps, a still better plan, both questions and answers may be written on different coloured paper, and then, after being shuffled, may be read aloud by the leader of the game.

In this game all the adverbs that can be thought of will need to be brought into requisition. Seated in order round the room, the first player begins by saying to his neighbour, "Cupid is coming." The neighbour then says, "How is he coming?" To which the first player replies by naming an adverb beginning with the letter A. This little form of procedure is repeated by every player until every one in the room has mentioned an adverb beginning with A. Next time Cupid is declared to be coming Beautifully, Bashfully, Bountifully, etc.; then Capriciously, Cautiously, Carefully, and so on, until the whole of the alphabet has been gone through, by which time, no doubt, it will be thought desirable to select another game.

A hassock is placed end upwards in the middle of the floor, round which the players form a circle with hands joined, having first divided themselves into two equal parts.

The adversaries, facing each other, begin business by dancing round the hassock a few times; then suddenly one side tries to pull the other forward, so as to force one of their number to touch the hassock, and to upset it.

The struggle that necessarily ensues is a source of great fun, causing as much or even more merriment to spectators of the scene than to the players themselves. At last, in spite of the utmost dexterity, down goes the hassock or cushion, whichever it may be; some one's foot is sure to touch it before very long, when the unfortunate individual is dismissed from the circle, and compelled to pay a forfeit.

The advantages that the gentlemen have over the ladies in this game are very[21] great; they can leap over the stool and avoid it times without number, while the ladies are continually impeded by their dresses. It generally happens that two gentlemen are left to keep up the struggle, which in most cases is a very prolonged one.

This game is not fit for very young children, but among older ones, who wish to enjoy a little quiet time together, it will suit their purpose admirably. On a little slip of paper each member of the party writes down a subject for definition. The slips are then handed to the leader, who reads the subjects aloud, while each person copies them on a piece of paper. Every one is then requested to give definitions, not only of his own word, but of all the others, the whole being read aloud when finished.

After dividing the company into two equal parts, one half leaves the room; in their absence the remaining players fix upon a verb, to be guessed by those who have gone out when they return. As soon as the word is chosen, those outside the room are told with what word it rhymes. A consultation ensues, when the absent ones come in and silently act the word they think may be the right one. Supposing the verb thought of should have rhymed with Sell, the others might come in and begin felling imaginary trees with imaginary hatchets, but on no account uttering a single syllable. If Fell were the right word, the spectators, on perceiving what the actors were attempting to do, would clap their hands, as a signal that the word had been discovered. But if Tell or any other word had been thought of, the spectators would begin to hiss loudly, which the actors would know indicated that they were wrong, and that nothing remained for them but to try again. The rule is that, while the acting is going on, the spectators as well as the actors should be speechless. Should any one make a remark, or even utter a single syllable, a forfeit must be paid.

Just as absurd and ridiculous as the representation of the Giant (elsewhere explained) is that of the Dwarf, and to those who have never before seen it performed the picture is certainly a most bewildering one. The wonderful phenomenon is produced in the following manner:—On a table in front of the company the dwarf makes his appearance, his feet being the hands of one of the two gentlemen who have undertaken to manage the affair. His head is the property of the same gentleman, while his hands belong to the other gentleman, who thrusts them over the shoulders of his companion to take the place of those that are being made to act as feet. Stockings and shoes are of course put on to these artificial feet, and the little figure is dressed up as well as can be managed, in order to hide the comical way in which the portions of the two individuals are united. For this purpose a child's pinafore will be found as suitable as anything else. A third person generally takes part in the proceedings as exhibitor, and comes forward to introduce his little friend, perhaps as Count Borowlaski, the Polish dwarf, who lived in the last century, and who was remarkable for his intelligence and wit. This little creature was never more than three feet high, although he lived to be quite old. He was also very highly accomplished: he could dance, and played on the guitar quite proficiently. Or he might be introduced as Nicholas Ferry, the famous French dwarf, who was so small that when he was taken to church to be christened his mother made a bed for him in her sabot, and so comfortable was he in it that for the first six months of his life it was made to serve as a cradle[22] for the little fellow. Sense or nonsense may of course be improvised on the spot, and made use of in order to render the exhibition a success.

Seated round the room, one of the company holds in his hand a ball, round which should be fastened a string, so that it may be easily drawn back again. Sometimes a ball of worsted is used, when a yard or two is left unwound. The possessor of the ball then throws it first to one person then to another, naming at the time one of the elements; and each player as the ball touches him must, before ten can be counted, mention an inhabitant of that element. Should any one speak when fire is mentioned he must pay a forfeit.

If it were not understood that joking of all kinds is considered lawful in most game playing, we might be inclined to think that in this game of the Farmyard a little unfairness existed in one person being made so completely the laughing-stock of all the rest. Still, as "in war all things are fair," so it seems to be in amusements, most hearty players evidently being quite willing to be either the laughers or the laughed at. The master of the ceremony announces that he will whisper in the ear of each person the name of an animal which, at some signal from him, they must all imitate as loudly as possible. The fact is, however, that to one person only he gives the name of an animal, and that is the donkey; to every one else he gives the command to be perfectly silent. After waiting a short time, that all may be in readiness, he makes the expected signal, when, instead of a number of sounds, nothing is to be heard but a loud bray. It is needless to remark that this game is seldom called for a second time in one evening.

A small flossy feather with very little stem must be procured. The players then draw their chairs in a circle as closely together as possible. One of the party begins the game by throwing the feather into the air as high as possible above the centre of the ring formed. The object of the game is to keep it from touching any one, as the player whom it touches must pay a forfeit; and it is impossible to imagine the excitement that can be produced by each player preventing the feather from alighting upon him. The game must be heartily played to be fully appreciated, not only by the real actors of the performance, but by the spectators of the scene. Indeed, so absurd generally is the picture presented, that it is difficult to say whether the players or the watchers have the most fun.

The principle of the following puzzle is very similar to that contained in "Think of a Number."

First of all a ring must be provided, after which you can request the company to put it upon some one's finger, adding at the same time that you will tell them who has it, and also upon which hand, and even upon which finger it shall have been placed.

The ring being deposited on a certain finger, you must then ask some one to make for you the necessary calculation.

Multiply the number of the person having the ring by 2; to that add 3. Multiply this by 5; then add 8 if the ring be on the right hand, or 9 if on the left. Then multiply by 10, and add the number of the finger (the thumb is 1); and, lastly, add 2.

Ask now for the result, from which subtract mentally 222, and the remainder will give the answer.

For instance, supposing the ring were put on the fourth person, on the left hand, and the first finger, remembering that the thumb counts 1.

The following is the kind of sum to be worked out:—

| The number of the person multiplied by 2 | 8 |

| Add 3 | 11 |

| Multiply by 5 | 55 |

| Add 9 for the left hand | 64 |

| Multiply by 10 | 640 |

| Add the number of the finger 2 | 642 |

| Add 2 | 644 |

| —— | |

| Subtract | 222 |

| —— | |

| 422 |

Which result proves it to be, beginning at the right-hand finger, the second finger of the left hand of the fourth person.

When the number of the person wearing the ring is above 9, the remainder will stand in four figures instead of three; in that case the first two will indicate the person.

Like all games of mental calculation, the more quickly this is done the better.

To play this game well it is necessary that there should be a good spokesman in the company, who will find ample opportunity for his gift of eloquence.

Simple as the game may appear to be, it is one that is generally played with very great success.

Each member of the party wishing to take part in it must place the right hand upon the left arm.

The leader then intimates that in the discourse with which he intends to favour his friends, whenever he mentions a creature that can fly, every right hand is to be raised and fluttered in the air in imitation of a bird flying. At the mention of all animals that cannot fly, the hands remain stationary. It is, of course, needless to say that the leader will do his best to have the hands raised when other animals are mentioned as well as flying ones, in order that a good number of forfeits may be collected.

All being in readiness, he will begin in a style something like the following:—

"One lovely morning in June I sallied forth to take the air. The honey-suckle and roses were shedding a delicious perfume, the butterflies and bees were flitting from flower to flower, the cuckoo's note resounded through the groves, and the lark's sweet trill was heard overhead. It seemed, indeed, that all the birds of the air (here all hands must be raised) were vieing with each other as to whose song should be the loudest and the sweetest, when," &c.

Thus the game is carried on until as many forfeits as are deemed desirable have been extracted from the company.

As an evening spent in playing round games would be thought incomplete if at the end of it the forfeits were not redeemed, so our book of amusements would be sadly lacking in interest if a list of forfeits were not provided. Indeed, many young people think that the forfeits are greater fun than the games themselves, and that the best part of the evening begins when forfeit time arrives. Still,[24] although we will give a list of forfeits, it is by no means necessary that in the crying of them none but certain prescribed ones should be used. The person deputed to pronounce judgment on those of his friends who have had to pay the forfeits may either invent something on the spur of the moment, or make use of what he has seen in a book or may have stored in his memory. Originality in such cases is often the best, simply because the sentence is made to suit, or rather not to suit, the victim; and the object of course of all these forfeit penances is to make the performers of them look absurd. For those players, however, who in preference to anything new still feel inclined to adopt the well-known good old-fashioned forfeits, we will supply a list of as many as will meet ordinary requirements.

1. Bite an inch off the poker.—This is done by holding the poker the distance of an inch from the mouth, and performing an imaginary bite.

2. Kiss the lady you love best without any one knowing it.—To do this the gentleman must of course kiss all the ladies present, the one he most admires taking her turn among the rest.

3. Lie down your full length on the floor, and rise with your arms folded the whole time.

4. Kneel to the wittiest, bow to the prettiest, and kiss the one you love best.—These injunctions may, of course, be obeyed in the letter or in the spirit, just as the person redeeming the forfeit feels inclined to do.

5. Put yourself through the keyhole.—To do this the word "Yourself" is written upon a piece of paper, which is rolled up and passed through the keyhole.

6. Sit upon the fire.—The trick in this forfeit is like the last one. Upon a piece of paper the words, "The fire," are written, and then sat upon.

7. Take one of your friends upstairs, and bring him down upon a feather.—Any one acquainted with this forfeit is sure to choose the stoutest person in the room as his companion to the higher regions. On returning to the room the redeemer of the forfeit will be provided with a soft feather, covered with down, which he will formally present to his stout companion, obeying, therefore, the command to bring him down upon a feather.

8. Kiss a book inside and outside without opening it.—This is done by first kissing the book in the room, then taking it outside and kissing it there.

9. Place a book, ornament, or any other very small article on the floor, so that no one in the room can possibly jump over it.—The way this is done is to place the article close to the wall.

10. Shake a sixpence off the forehead.—It is astonishing how even the most acute player may be deceived by this sixpenny imposition. The presiding genius, holding in his fingers a sixpence, proceeds with an air of great importance to fasten the coin upon the forehead of the victim, by means of first wetting it, and then pressing it firmly just above the eyes. As soon as the coin is considered to be firmly fixed, he takes away his hands, and also the coin. The person operated upon is then told to shake the sixpence down to the floor, without any aid from his hands, and so strong generally is the impression made upon the mind of the victim that the sixpence is still on the forehead, that the shaking may be continued for several minutes before the deception be discovered.

11. Put one hand where the other cannot touch it.—This is done by merely holding the right elbow with the left hand.

12. Kiss the candlestick.—Request a young lady to hold a lighted candle, and then steal a kiss from her.

13. Laugh in one corner of the room, sing in another, cry in another, and dance in another.

14. Leave the room with two legs, and return with six.—To do this you must go out of the room, and come back bringing a chair with you.

15. Put four chairs in a row, take off your boots, and jump over them.—This task would no doubt appear rather formidable for a young lady to perform, until she is made to understand that it is not the chairs, but the boots, she is expected to jump over.

16. Blow a candle out blindfold.—This forfeit is very similar to the game, elsewhere described, of Blowing out the Candle; still, there is no reason why it should not take its place among the rest of the forfeits. The victim is blindfolded, turned round a few times, and then requested to blow out the light. When the performance is over, the owner of the forfeit will no doubt have well deserved to have his property returned to him, for if securely blindfolded the task will have been no easy one. Another way of blowing out the candle is to pass the flame rapidly backwards and forwards before the mouth of the player, who must try to blow it out as it passes, a method that is almost, if not quite, as difficult as the former one.

17. The German band.—In this charming little musical entertainment, three or four of the company can at the same time redeem their forfeits. An imaginary musical instrument is given to each one—they themselves must have no choice in the matter—and upon these instruments they must perform as best they can.

18. Ask a question, the answer to which cannot possibly be answered in the negative.—The question, of course, is "What does y-e-s spell?"

19. The Statue.—The unfortunate individual doomed to redeem his forfeit by acting a statue must allow himself to be placed in one position after another by different members of the company, and thus remain stationary until permission is given him to alter it.

20. The Sentence.—A certain number of letters are given to the forfeit-payer, who must use each one in the order in which it is given him for the commencement of a word. All the words, when made, must then form a sentence—placing the words in their proper order exactly as the letters with which they begin were given.

21. Comparisons.—The gentleman or lady must compare some one in the room to some object or another, and must then explain in which way he or she resembles the object, and in which way differs from it. For instance, a gentleman may compare a lady to a rose, because they are both equally sweet; unlike the rose, however, the lady is of course, without a thorn.

22. The Excluded Vowels.—Pay five compliments to some lady in the room. In the first one the letter a must not occur, in the second the letter e must be absent, in the third there must be no i, in the fourth no o, and in the fifth no u.

23. Kiss your own shadow.—The most pleasant method of executing this command is to hold a lighted candle so that your shadow may fall on a young lady's face, when you must take the opportunity of snatching a kiss.

24. Form a blind judgment.—The person upon whom the sentence has been passed must be blindfolded. The company are then made to pass before him one by one, while he not only gives the name of each, but also his opinion concerning them.

Not unfrequently the victim has to remain blindfold a very long time, for even if the name should be guessed correctly, it is no easy matter to form a just estimate of character, and unless his ideas meet with the approbation of the company, his forfeit is withheld from him.

Great silence must be observed while the ordeal of examination is going on. No one should speak, and all should step as lightly as possible.

25. Act the dummy.—You must do whatever any of the company wish you to perform without speaking a single word.

26. The telegraphic message.—Send your lover's name by telegram to the other end of the room. To do this you must whisper the favoured name to the person sitting next to you, who will whisper it to his neighbour, and so on until every one has been made acquainted with it.

27. Act the Prussian soldier.—This penance is one that is generally performed only by gentlemen. The uniform assumed is usually a coat turned inside out, a hat made of a twisted newspaper, a bag of some description for a cartridge-box, and soot moustaches.

Holding a walking-stick in a military style, the penitent goes up to a lady, presents arms, and stamps three times with his feet.

Rising from her seat, the lady must accompany the gentleman to the opposite side of the room, then whisper in his ear the name of the gentleman for whom she has a special preference.

Without speaking the brave Prussian must march up to the favoured gentleman, and escort him across the room to the side of the lady who has avowed herself his admirer. The lady is, of course, saluted by the object of her choice, after which she is taken back to the seat she originally occupied. The soldier then, presenting arms, returns to the gentleman, who whispers in his ear a favoured lady's name, to whom he escorts her admirer. The proceeding is thus carried on, until some lady is good enough to acknowledge her preference for the soldier himself above all the other gentlemen, when, after saluting the lady, he is at liberty to lay aside his military dress, and return to his seat.

28. "'Twas I."—The victim in this case is unmistakably doomed to occupy a very humiliating position. He must go round the room, inquiring of each person what object he has seen lately that has particularly attracted his notice. The answer may be—a baby, a thief, a donkey; whatever it is, the unfortunate redeemer of the forfeit must remark—"'Twas I."

29. The acrostic.—A word is given to you, the letters of which you must convert into the first letters of a double set of adjectives, one half expressing good qualities, the other half bad ones. When complete you may present both good and bad qualities to the person you most admire, as expressive of your estimate of his or her character. For instance, should the word given you be Conduct. If a gentleman, you might inform your lady that you consider her—

C areful.

O rderly.

N oble.

D elightful.

U seful.

C ompassionate.

T idy.

while at the same time you think her to be—

C aptious.

O bnoxious.

N iggardly.

D eceitful.

U ntidy.

C ross.

T ouchy.

30. The three words.—The names of three articles are given to you, when on the spur of the moment you must declare to what use you would put them if they were in your possession for the benefit of the lady you admire. Supposing the words to be, a penknife, a half-crown, and a piece of string, you might say:—"With the penknife I would slay every one who attempted to place any[27] barrier between us; with the half-crown I would pay the clergyman to perform the marriage ceremony; and with the string I would tie our first pudding."

31. Make a perfect woman.—To do this the player has to select from the ladies present the personal features and traits of character that he most admires in each, and imagine them combined in one individual. Although the task is by no means one of the easiest, it may be made the opportunity of paying delicate little compliments to several ladies at once.

32. Show the spirit of contrary.—The idea in this imposition is the same as in the game of contrary. Whatever the player is told to do, he must do just the contrary.

33. Give good advice.—Go round the room, and to every one of the company give a piece of good advice.

34. Flattering speeches.—This penance is usually given to a gentleman, though there is no reason why the ladies should always be exempted from its performance. Should it be a gentleman, however, he must make six, twelve, or as many flattering speeches as he is told to a certain lady, without once making use of the letter L. For instance, he may tell her she is handsome, perfect, good, wise, gracious, or anything else he may choose to say, only whatever adjective he makes use of must be spelt without the letter L.

35. The deaf man.—This cruel punishment consists in the penitent being made to stand in the middle of the room, acting the part of a deaf man. In the meantime the company invite him to do certain things, which they know will be very agreeable to him. To the first three invitations he must reply—"I am deaf; I can't hear." To the fourth invitation he must reply—"I can hear"; and, however disagreeable the task may be, he must hasten to perform it. It is needless to say the company generally contrive that the last invitation shall be anything but pleasant.

36. Act the parrot.—The player condemned to this penance must go round the room, saying to every one of the company—"If I were a parrot, what would you teach me to say?" No end of ridiculous things may be suggested, but the rule is that every answer shall be repeated by the parrot before putting another question.

37. Make your will.—The victim in this case is commanded to say what he will leave as a legacy to every one of his friends in the room. To one he may leave his black hair, to another his eyebrows, to another (perhaps a lady) his dress coat, to another his excellent common sense, to another his wit, and so on until every one in the room has been remembered.

38. Spell Constantinople.—This trick, as most people are aware, consists in calling out "No, no!" to the speller when he has got as far as the last syllable but one. Thus he begins:—"C-o-n con, s-t-a-n stan, t-i ti." Here voices are heard crying "No, no!" which interruption, unless the victim be prepared for it, may lead him to imagine that he has made a mistake.

39. The natural historian.—Go to the first player, and ask him to name his favourite animal. Whatever animal he may mention, you must imitate its cry as loudly as you can. You then ask the second player to do the same, and so on until you shall have imitated all the animals mentioned, or until the company shall declare that you deserve to have your forfeit returned to you.

40. The blind dancers.—Among players who are not anxious to prolong the ordeal of forfeit crying any longer than is necessary, the following method of redeeming several forfeits at once may be acceptable:—Eight victims are chosen to be blindfolded, and while in this condition are requested to go through the first figure of a quadrille.

41. The cats' concert.—This is another method of redeeming any number of forfeits at once. The players who have their forfeits to redeem are requested to[28] place themselves together in a group, when, at a given signal from the leader, they all begin to sing any tune they like. The effect, as may well be imagined, is far from soothing.

42. Spelling backwards.—Spell some long word, such as hydrostatics, &c., backwards.