The Project Gutenberg EBook of Marooned in the Forest, by A. Hyatt Verrill

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: Marooned in the Forest

The Story of a Primitive Fight for Life

Author: A. Hyatt Verrill

Release Date: February 17, 2020 [EBook #61427]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK MAROONED IN THE FOREST ***

Produced by Roger Frank (This book was produced from images

made available by the HathiTrust Digital Library as

digitized by Google.)

MAROONED IN THE FOREST. Illustrated.

HARPER’S BOOK FOR YOUNG NATURALISTS.

Illustrated. 8vo

HARPER’S WIRELESS BOOK

Illustrated. Crown 8vo

HARPER’S AIR CRAFT FOR BOYS

Illustrated. Crown 8vo

HARPER’S BOOK FOR YOUNG GARDENERS.

Crown 8vo

HARPER’S GASOLINE-ENGINE BOOK.

Illustrated Crown 8vo.

If a man or a well-grown boy is lost in the wilderness, what can he do? Shall he whimper and give up? Never, if he has real blood in his veins. He faces a primitive struggle for life. It is a question of reinventing primitive means of living. How to make a fire, how to obtain food, how to clothe and shelter himself—these are the immediate problems to be met. He is a Robinson Crusoe of the wilderness.

This story of a modern Crusoe in the far Northern forests embodies many actual experiences, and it is an epitome of the basic facts of outdoor life. In books like Harper’s Camping and Scouting, Outdoor Book, Young Naturalists, and others, the appliances of civilization are always at hand. It is a very different situation when one is lost in the depths of the forest without food, fire, weapons, or compass. But the problem of working out means of existence is one that will interest every lover of outdoor life, whether his interest is in camping, canoeing, fishing, or hunting, whether he is a member of the Boy Scouts or the Woodcraft Indians or simply an individual who knows the call of the wild. The adventures of Mr. Verrill’s hero forth a story of thrilling interest and constant suspense. And it is also full of suggestions which will stimulate many readers to work out some of the hero’s problems for themselves.

It all happened in the twinkling of an eye. I turned quickly at a sudden cry from Joe—my half-breed guide—in time to see him cast the handle of his broken paddle aside and leap forward for the extra paddle. Before he could reach it the canoe swerved, swung broadside to the rushing current, crashed sickeningly against the jagged rocks, and the next instant I was floundering about in the icy, swirling water. Bumping against rocks, struggling for breath, battling frantically with the torrent, I was swept down the river. Time and again my feet touched bottom, but each time, ere I could gain a foothold, I was drawn under, and each second I realized that my strength was growing less, that my lungs were bursting for air, and that in a few more moments all would be over. Down, down, I sank; above me the green water closed in and from my mouth and nostrils tiny bubbles of escaping air rose upward despite my every effort to withhold the scanty breath within my lungs. I was drowning I knew, and vaguely I wondered what had become of Joe, and how my friends would take the news of my loss here in this river of the great wilderness. Suddenly my foot touched a hard object. I threw all of my last remaining strength into a spasmodic kick and lost consciousness.

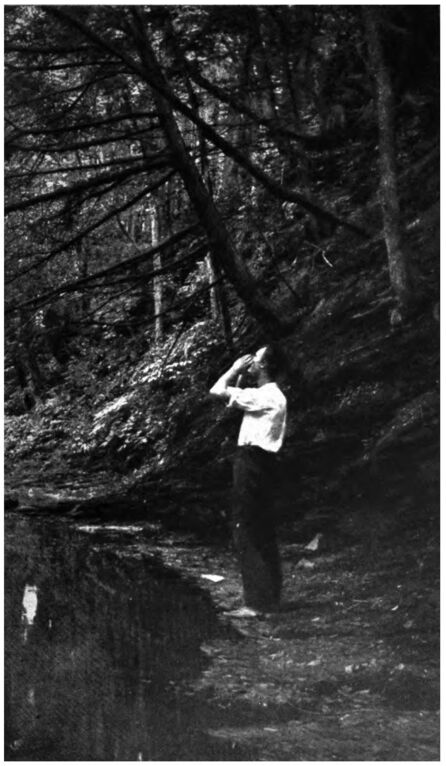

Slowly I opened my eyes and with wonder looked upon a strip of deep-blue sky against which the dark-green boughs of evergreens were sharply outlined. For a space I marveled, for so firmly convinced had I been that I was drowned I could scarce realize that I was not looking with spiritual eyes at a scene in another world. Then it dawned upon me that through some miracle I had been saved, and with a mighty effort I sat up.

I found myself upon the very brink of a little precipice—a natural dam over which the river fell in a miniature cataract, although the greater portion of the current swept to the left and poured like a mill-race through a narrow channel in the rocks. In a moment I realized how I had escaped. My final kick had driven me beyond the sweep of the current, I had been washed upon the edge of the waterfall, and my position had allowed the water to drain from my lungs. I was still terribly weak, I was choking with the water I had swallowed, my head swam, and with the utmost difficulty I half crawled, half waded to the shore and threw myself upon the moss-covered bank where rays of sunshine penetrated the foliage overhead.

Although I was saved from death in the river by the merest chance, still my plight was desperate, for I was alone in the heart of the great woods, miles from civilization or settlements and without food, weapons, shelter, or anything save the clothes upon my back and the few trifles my pockets might contain. Possibly, I thought, the canoe might be washed ashore with its contents, or Joe might be safe and in the vicinity; and with these ideas strong in my mind I rose and slowly walked along the river’s bank. I was now rapidly regaining strength, and, with the aid of a stout pole of dead wood which I picked up, I had little trouble in making my way up the stream. Presently I called out Joe’s name, but only the soft echo of the woods replied. Again I trudged on, frequently calling and ever searching the edges of the stream and the eddies for the wreckage of the canoe, but not a sign of my guide or of my outfit could I find. At last, firmly convinced that Joe had been lost and that the canoe and its contents were gone forever, I seated myself upon a log and strove to collect myself and look squarely at the future. It would have been bad enough to be cast away in a country which I knew, but here I was completely at a loss. I had trusted entirely to Joe, and I knew nothing of this wilderness nor of the direction or route to the settlements; while, to make matters still worse, my compass had been lost in the river.

The last was really the least of my troubles, for I had little doubt that I could readily determine which direction was east and which west by the sun, and I had also heard that the moss grew thickest on one side of the trees; but as to whether that side was north or south I could not remember, cudgel my brains as I might. I also knew, in a general way, that the settlements were southward from the camp we had left, and I knew that Joe had expected to reach them by running down with the current, paddling across a lake, and tramping through the woods, and that he had stated the entire trip would consume about five days. However, I could not even I guess how many miles we had traveled before the canoe upset, and I had taken no notice of the turns and twists in the river. For all I knew, the stream might flow east, or even north, at the spot where I had crawled ashore, and if I attempted to travel in any direction—using the flow of the current as my guide—I might easily travel directly away from my fellow-men.

My sole hope of reaching civilization would be in following the banks of the river, and this I realized would mean many weary days of tramping alone and unguided through the great forest.

Vainly I regretted having trusted so completely to Joe that I had paid no attention to the surroundings as we swept down the stream, and for that matter had not even asked for information which would have proved so valuable to me now. But it was wasting valuable time to spend the few remaining hours of daylight in regrets, and I was thankful for the few odds and ends of woodcraft and forest lore I had picked up during my life in the woods.

My clothing had partly dried, but with the passing of the bit of sunlight from the opening between the trees the air had become chilly and I was shivering with cold, the strain of my recent experience and my forebodings for the future. Rising from my seat, I strode back and forth, swinging my arms and striving by exercise to regain in some measure the circulation of my blood and a feeling of warmth. Activity, even of this forced sort, did me a world of good, and I began to plan for my immediate wants. Shelter I must have, and warmth, before night fell, and while I was not at the moment hungry, I realized that food of some sort would become a most pressing need by the following morning. Shelter without warmth would be of little value, and I thought with longing of the roaring fires which Joe had built before our camps each night and about which we had lounged while telling tales of past adventures.

Fire I must obtain, and in a mad hope that at least one good match might still remain in my pockets, I sought feverishly and emptied every one of my pockets upon a smooth rock. My total possessions thus displayed consisted of a small bunch of keys, a few small coins, a cambric handkerchief, a heavy jackknife, and the headless sticks of some matches from which the phosphorus had been completely soaked off. I gazed at these few articles with the bitterest disappointment, for of them all the knife was, as far as I could see, the only thing of any value to me in my present plight. With it I thought I might be able to fashion a bow-drill and spindle and thus obtain fire, for in my youth I had accomplished this feat when “playing Indian,” but I well knew the difficulty in obtaining just the proper kinds of wood and I realized that a search for them would consume much valuable time, whereas but an hour or two of daylight now remained. Then flint and steel occurred to me. I had the steel in my knife, but I did not know whether flint was to be obtained in the vicinity. However, I rose, made my way to the stony edge of the river, and sought diligently for some bit of rock which resembled flint. Each piece that struck my fancy I tried with my knife, and several gave off faint, bright sparks. All these I pocketed and, having obtained quite an assortment, I retraced my way to the rock whereon I had left my other possessions and prepared to try my hand at obtaining fire by means of my knife and the pebbles.

I realized that the tiny sparks which I could obtain in this way would never ignite a twig, or even a bit of bark, and that some inflammable tinder, which would catch the spark and which could then be fanned to a flame, must be secured before I could hope to succeed. As I was thinking of this my gaze fell upon a black-edged hole in my handkerchief. It had been burned, a couple of days before, by a spark from Joe’s pipe blown back by the wind. The incident was too trivial to have filled my thoughts for an instant at another time, but now all its details came back to me with a rush and I gave a shout of joy as I suddenly realized that this burnt hole and the events which had caused it had actually solved my puzzle. Seizing the square of cotton cloth, which was now quite dry, I weighted it down with bits of stone—for the apparently useless handkerchief had now become of the utmost value to me—and hurried into the woods in search of dry twigs and other inflammable material. I had not long to hunt, for dead and dried trees were all about; several white birches furnished sheets of paper-like bark, and with a great armful of fire-wood I returned to my rock. Gathering the handkerchief into a loosely crumpled mass, I placed it on the rock, held the most promising of my pebbles close to it, and struck the stone sharply with the back of my knife-blade. A little shower of sparks flew forth at the blow, but none fell upon the handkerchief. Again and again I tried, each time holding the stone in a different position and trying my best to cause the sparks to fall upon the handkerchief. Finally I gathered the cloth in my hand, held the pebble in the midst of its folds, and struck it.

Sparks gleamed against the handkerchief, but no sign of charring cloth or wisp of smoke rewarded me. Surely, I thought, these sparks must be as hot as the tiny, glowing ember from Joe’s pipe, and I unfolded and examined the handkerchief about the burned spot. Perhaps, I thought, this particular part of the cloth was more inflammable than the rest, and again gathering up the handkerchief, with the old burn close to the pebble, I again struck it with my knife.

Carefully I examined the cloth and the next instant dropped knife and pebble and cried aloud in triumph, for at one edge of the charred hole a tiny speck of red glowed in the dusk of coming evening, and spread rapidly in size. Carefully I blew upon it, folded another corner of the cloth against it, and waved it back and forth. Brighter and brighter it gleamed; a tiny thread of pungent smoke arose from it and an instant later a little tongue of flame sprang from the cambric, and I knew that fire, warmth, and comfort were mine. It was but an instant’s work to ignite a piece of birch bark and push it among the pile of wood and twigs, and then, carefully extinguishing the handkerchief—for it had now grown very precious in my eyes—I squatted before the blazing fire and reveled in the comforting warmth from its glow. Although it was too late to consider ways and means of shelter that night, I knew that I could keep warm, and as soon as the chill and stiffness had been driven from my bones and muscles I set diligently at work gathering great piles of fuel to feed the flames during the night. Several large logs were close by, and these, with much labor, I dragged to the fire and placed near at hand to use later on when I went to sleep. By the time I had accumulated a supply which I judged would last through the night, I discovered that I was very hungry. I had not eaten since the forenoon, and I had worked strenuously, to say nothing of the utter exhaustion occasioned by my semi-drowning. My efforts to obtain fire and the extent to which I had concentrated my mind on this problem had kept me up and doing until now, but, once the fire was blazing merrily and an ample supply of fuel was at hand, I felt weary beyond words, famished, and absolutely worn out.

The sun had set and the forest was black as midnight, but the sky was still faintly bright with the afterglow and the river shone silvery as it swirled and eddied between its shadowy banks. There was no hope of finding berries, roots, or other edibles in the woods after dusk. I had no means of catching game or fish, which, I knew, were abundant, and I commenced to think that I would die a miserable death of starvation before morning, when I suddenly recollected having seen a number of fresh-water mussels in some shallow backwaters of the river while hunting for my flinty pebbles. I had never eaten these shell-fish, but I felt sure they were edible, and, seizing a blazing pine knot from the fire, I made my way to the shore and soon found the pools where I had noticed the mollusks. There were not many—a bare dozen were all I could find that night—but these I felt would be far better than nothing, and in a few moments I had them baking on a bed of hot coals. Hardly waiting for them to cook, I raked them forth and devoured them ravenously, and never did choicest food taste so delicate, so delicious, and so welcome to my lips as did those half-baked, slimy, unseasoned mussels eaten beside my fire in the midst of the wilderness. Few as they were, they served to refresh me greatly and to drive away the most pressing pangs of hunger, and, much as I desired more, I had not the strength or ambition to trudge up and down the river-bank searching for the shells. Piling several huge logs on the fire, I formed a rude bed of fir twigs and, casting myself upon this, fell instantly into a deep, dreamless sleep.

I was awakened by a shaft of sunlight striking my face, and opened my eyes to find the day well advanced. My first thought was of the fire, which had burned completely out. A thread of bluish smoke rose from the heap of ashes, however, and by raking these aside and thrusting bits of birch bark amid the embers I soon had a new blaze started, which I piled high with dry wood. I was wonderfully strengthened and refreshed by my long sleep, but I was all but famished, and as soon as the fire was going well I hurried to the river for more mussels. I found a few here and a few there, and with a dozen or two went back to the fire and presently was breakfasting off the shell-fish. I realized that while these would serve to prevent me from dying of hunger and they were wonderfully welcome in my present starved condition, I would be forced to search for something else to eat very soon. In the first place, the supply of the bivalves was limited. They would, I felt, prove far from palatable save when I was very hungry, and I doubted how much nourishment was contained in their flabby meat.

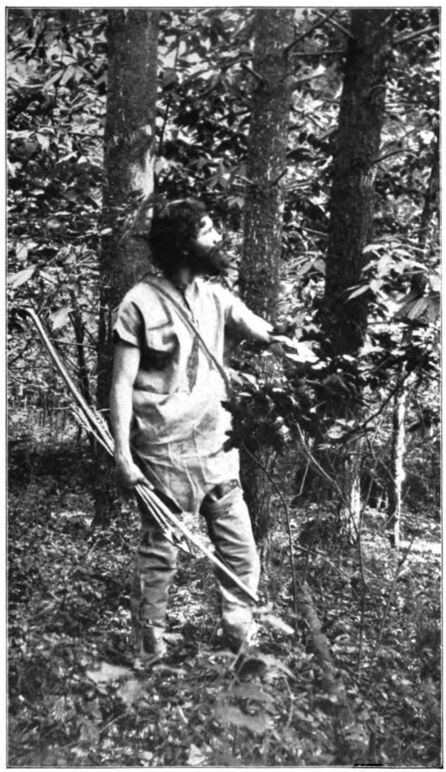

Had I possessed firearms or even fishing-tackle my plight would not have been bad, for birds and animals could, I knew, be readily found in the woods, while trout and other fish were abundant everywhere in the wilderness streams. As I ate my mussels I sought to devise some method of securing game, but every plan that occurred to me was spoiled by some unsurmountable obstacle which arose. I had often snared game and had even caught partridges with a slender noose on the end of a pole—for in the north woods these birds sit stupidly upon the low fir-trees and allow the hunter to pull them from their perches without taking flight. But a snare required a fine line, a slender wire, or a horsehair, and I had none. Fishing with a line was cast aside as out of the question for the same reason, with the added lack of a hook. Then a bow and arrow occurred to me, but I soon realized that arrows without feathers or sharp, heavy points would be impossible, and that neither heads nor feathers were within reach. Then I thought of spears, for I knew that many savage tribes used spears both in fishing and in hunting, and I decided to try my skill at harpooning some unsuspicious fish or some unusually stupid partridge. It was a long time before I could find a straight, light stick for a haft, but at last I found a slender pole of weathered, dried spruce cast up by the river, and, by dint of whittling and trimming, this was worked into a very straight, well-balanced shaft which I judged would fulfil my requirements. I tried throwing it several times and found it easy to handle, but that it could not be depended upon, for one end was nearly as heavy as the other and it would fly sideways and strike a glancing blow as frequently as it would strike end on.

I realized that a head of some sort was required, but this I could not furnish, and rather than lose all the time I had spent on it I determined to try my hand at spearing a fish before throwing my weapon aside. Whittling the end to a sharp point and cutting numerous barbs, or notches, in it, I walked to the river and looked carefully into each pool and backwater. I saw several fish, but each flitted out of view as the spear was plunged downward, and I was about to abandon my attempts when luck favored me. Approaching one small pool, I gave a little start as a great bullfrog leaped almost from beneath my feet with a loud croak. A moment later he appeared on the farther side of the pool, his goggly eyes just showing above the water, and, approaching him carefully, I drove my sharpened stick at his big, green body. It was a lucky stroke, for the frog was fairly impaled upon the stick, and I drew my first victim from his watery home with a wonderful feeling of elation to think that unaided and alone I had actually succeeded in hunting and capturing a live, wild creature to serve my needs.

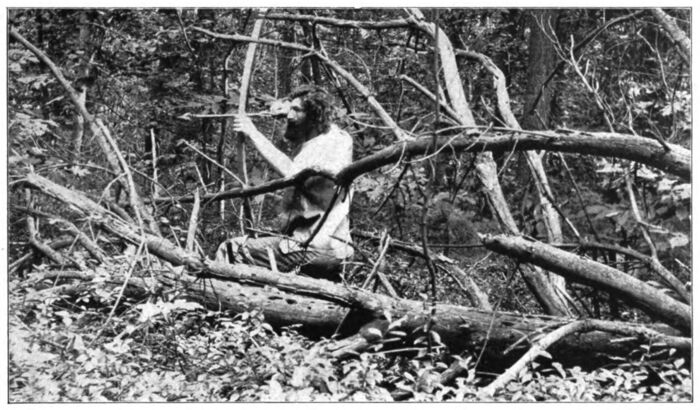

Strangely enough, frogs had not occurred to me hitherto, but, now that I had obtained one, I bestirred myself to capture a number. I realized that with my crude spear I could not expect to kill many frogs, and that my first success was pure luck more than anything else. Many a time when a boy I had speared frogs when spending my summers on a farm, and now that frogs were in my mind I remembered the two- or three-pronged spears which the farmers’ boys used. I was still hungry, and while my frog was broiling I busied myself in making a real frog-spear. It was not a difficult task. I had only to attach two slender, barbed pieces of hard wood to the sides of my spear. I had some trouble in binding them on, but I sacrificed strips of my clothing for the purpose, and although the completed spear was very crude, I felt sure it would serve its purpose. I knew, however, that it would soon be blunted and broken among the rocks of the river and I also knew that in such spots frogs would be scarce and that in muddy or stagnant pools I would stand a much better chance of finding them. No swamps or pools were in the immediate vicinity, but I had little doubt that I could find some by a short tramp. I was very anxious to try my spear, but I also realized that I must give time and thought to constructing a shelter to protect me in case of rain, and, reluctantly abandoning my frog-hunt for the time being, I gave my whole attention to the problem of house-building. I had seen many a shack or “lean-to” built and had helped at the work myself, but without an ax I knew that to build even the smallest and simplest shelter would necessitate a tremendous amount of hard labor and would present almost insurmountable difficulties. With only a pocket-knife to cut the necessary trees, poles, and branches, I would be obliged to make the shack of small stuff, and I trembled to think what fate might have in store for me if I should break my knife in an attempt to cut tough branches from the trees.

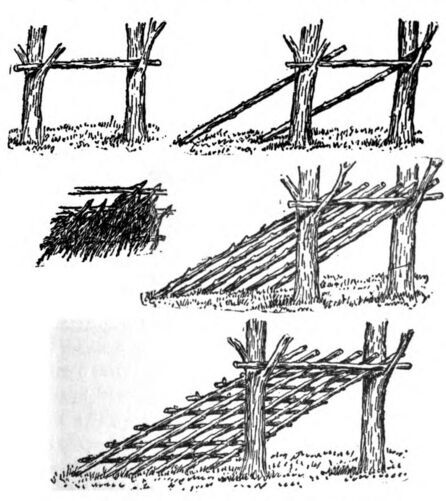

However, if I was to have a shelter at all it behooved me to begin at once, and I started forth to select a site for my home. I found a sheltered, dry knoll with good drainage a short distance from the river and with plenty of building material in the form of balsam firs, pines, and birches near at hand. I first selected two young trees, about five feet apart, and from these I cut the lower branches, leaving the stubs projecting a few inches. Across two of these I placed a light spruce pole and from the ends of this I laid other poles extending back at an angle to the ground.

This all sounds very simple and easy, now that I come to write it down, but as a matter of fact it required hours of hard, back-breaking, hand-blistering work, and by the time this much was accomplished I was faint with hunger. I succeeded in finding and eating a few mussels, but I had no time to devote to frog-hunting, and hurried back to my house-building. Across the two slanting poles other lighter poles were placed, and over these the broad “fans” of fir were spread like shingles, the lowest layer being placed first with each succeeding layer overlapping the last. This was comparatively easy work, for the twigs were small and easy to cut, and by late afternoon I had a shack which, though not by any means complete, was far better than nothing but the blue sky for a shelter.

I had an hour or two of daylight left, and determined to look for a likely spot for frogs. I dared not walk far into the forest for fear of losing my way in the fading afternoon light, but even a tramp of a few hundred yards away from the river was enough to convince me that there were no swamps or ponds in the vicinity, for the ground was quite hilly and rocky. Deciding that my only chance lay in finding stray frogs in the pools of the river, I walked down-stream for some distance, searching carefully wherever there was a backwater or a puddle of water along the shore. I found a number of mussels, which I pocketed, but no sign of frogs until I had traveled perhaps half a mile from my fire. At this point a small brook fell in a tiny cascade over the bank into the river, and, clambering up, I found that the little stream ran through an open vale or glade luxuriant with ferns, brush, and rank-growing plants. The stones over which it flowed were dark with a coating of moss, and in the deep, still pools between the boulders I caught glimpses of great speckled trout lurking in the shadows. It was an ideal trout-brook and I tried my best to spear one of the beautiful fish, but without success. However, I was rather pleased at my discovery, for even without fishing-tackle I felt confident that I could dam up one of the pools, bail out the water, and catch the trout with my hands. But there was no time for this just then. In the hope of finding a frog I went on up the brook. I had all but given up in despair when I reached a second miniature waterfall, and above this cascade I came upon a little pond surrounded by alders and birches. It was a cool, shady spot and the dark, black water flecked with patches of green weeds and lily-pads gave promise of frogs. Hardly had I reached the edge of the pool when I spied a fine bullfrog squatting among the weeds, and a moment later he had been successfully speared. I was delighted with the success of my crude weapon and crept cautiously around the pond, seeking more victims. Frogs were plentiful and were very tame, for probably man had never disturbed them, and before the growing dusk warned me that it was time to return to my camp I had obtained seven fine, big hoppers. As I was making my way toward the brook and the cascade I was startled by some good-sized creature which sprang from the grass at the border of the pond and plunged into the water. A moment later I saw a furry, brown head followed by a silvery, rippling wake, cleaving the placid surface of the pond, and realized that the animal which had caused my momentary fright was merely a harmless muskrat. I stopped and watched the creature for several moments and longed to be able to secure him, for I well knew that muskrats are edible and are even esteemed a delicacy. More than once I had eaten their tender, white meat when cooked by Joe. It was useless to give the matter any consideration, however, for without a gun the muskrat was far beyond my reach, and reluctantly I proceeded on my way.

Presently I noticed a path-like trail winding through the grass and weeds, and, looking closely, discovered the imprint of little feet upon the soft and muddy ground. I recognized the muskrat’s runway, and with the realization came the thought that I might trap the rats. To be sure, I had no traps at hand, but I had seen deadfalls set in the woods by the fur trappers and, while my memory was hazy as to just how they were arranged, I felt quite confident that my ingenuity would find a way to rig up some sort of snare or deadfall which would serve my purpose. With my mind filled with such thoughts I made my way back to my fire, which I reached just as darkness fell upon the wilderness. I dined well that night on frogs, and placed my mussels in a pool beside the river as a reserve for another day.

Much of the evening I spent experimenting with bits of twigs and sticks of wood, endeavoring to devise a deadfall, and by dint of racking my memory for details of traps I had seen, and by trying various methods, I finally discovered several different triggers which I felt would work, and, well satisfied with my day’s labors and success, I fell asleep upon a bed of soft fir branches in the lean-to.

A couple of the frogs, which I had kept over, with a few mussels, served for my breakfast the next morning, and I then set diligently at work to complete my shelter, for a light shower had fallen during the night and my clothes were soaking wet when I awoke. To make the roof water-tight was my first consideration and to accomplish this I peeled sheets of birch bark from the trees, laid them like shingles on the roof, and secured them in place by rocks from the river-bed. At first I had trouble in preventing the stones from sliding and rolling off the slanting roof, but I soon devised a means of holding them in position by placing light branches across the roof and catching their ends on the projecting stubs of the roof timbers. In many ways I was greatly handicapped for want of string or rope. It occurred to me that strips of birch bark might serve, but I soon found that this had no strength to speak of, and I determined to try other materials. The Indians, I well knew, used bark, roots, and withes for rope, but I had no knowledge of the particular barks, roots, or withes which they employed, and I set myself to experimenting with everything that grew in the neighborhood. I soon eliminated many as useless, although certain roots appeared tough and fibrous, but these were all too gnarled and knobby or too short to serve as string. It was then that I began to realize how little I really knew of woodcraft or forest lore, although I had spent so many vacations in the woods. No doubt Joe or any other woodsman would have found life easy and simple if cast, as I was, upon his resources in the forest, but I had depended so completely upon others’ knowledge that I was obliged to seek blindly for the simplest things and only occasionally remembered some trifling bit of woodcraft which I had seen when in Joe’s company in the forest.

While thinking of this I was sitting beside my hut. When I attempted to rise, my hand came in contact with a sharp stub projecting from the earth. It was a small thing—merely a twig which I had cut off while clearing the open space before my shelter—and to avoid further trouble with it, I grasped it and strove to pull it up. Much to my surprise, it resisted my efforts. Seizing it with both hands, I jerked at it with all my strength. Slowly it gave, and then, with a ripping sound, broke from the loose, thin earth, and I tumbled backward and sprawled upon the ground. I was curious to learn how such a small thing could be so strongly embedded in the soil and I examined it carefully. Attached to the bit of stem was a mass of long, fibrous roots. Seizing one of these, I attempted to break it. I twisted and pulled, but the root remained intact, and suddenly it dawned upon me that here was the very material I desired—that these roots were as strong and tough as hempen rope, and that by merest accident I had stumbled upon the very thing for which I had been searching. Unfortunately, I did not know what plant the roots belonged to, for only an inch or two of stem remained, and while the supply of roots it bore would serve my present needs, I was very anxious to learn the identity of the useful growth in case I should require more roots in the future. With this end in view I set about comparing the bark and wood with other young sprouts in the vicinity, and whenever one resembled it I pulled it up and examined the roots. I searched for some time before I was rewarded, and discovered that my lucky find was a young hemlock. Pine fir, spruce, and other trees I had tried in vain, but hemlocks were not abundant, and those about were mostly large and had been passed by in my former search. Now that I had discovered a source of supply of binding materials, many problems which had confronted me were simplified and I was greatly encouraged.

It must not be supposed that during these first days of my life in the wilderness I had given no thought to making my way to the settlements. In fact, this matter was ever present in my mind, but the very first day I had decided that before I attempted to make my way out of the woods I must be equipped to secure food, provide shelter, and make fires. Anxious as I was to reach civilization, yet I knew how foolhardy it would be to start blindly forth, trusting to luck for food or shelter, and with my limited knowledge of woodcraft. Here, where I had been cast ashore, I was safe, at any rate, provided I could secure enough to eat, and I determined to make my headquarters at this spot until I could learn by experience something of the resources of the forest and how to make use of them. Already I had acquired much useful knowledge, and I felt that if I could only succeed in trapping animals or snaring birds I could start forth on my weary tramp in comparative safety as far as starvation was concerned.

I should have felt far more confident if I could have carried food with me, and I wondered if it would be possible to dry or cure frogs, mussels, or other meat. I knew that the Indians dried venison and made pemmican, which I had frequently eaten, and I had heard of certain tribes who subsisted upon dried salmon, but venison was unattainable with my present resources, and I was not at all sure that trout, even if I succeeded in obtaining them, would dry like salmon. Finally I decided to experiment, and, lacking all else, to carry a supply of live mussels along when I set forth. These shells, I knew, would live for several hours without water, and, as I intended to follow the river, I could easily keep them alive by frequent immersions in the water. Such thoughts brought up the question of vegetables, and I wondered if in these woods there were edible roots or tubers of any kind.

I remembered many boyhood books and stories telling of men lost in the woods and subsisting upon roots and berries, but, try as I might, I could not remember a single one which told just what roots and berries provided sustenance for the fictitious heroes.

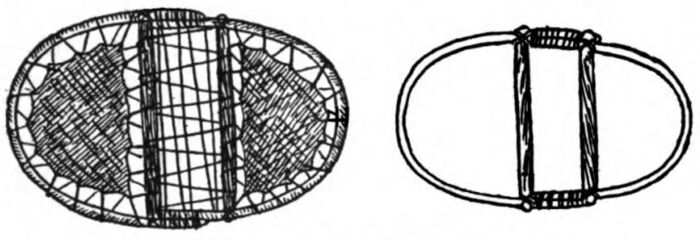

Berries, I felt sure, existed somewhere in the woods, but, aside from blueberries or blackberries and the tiny scarlet partridge berries, I knew of none which were edible, and I smiled to think how hungry I would be if I depended upon the meager and uncertain supply of such things for a livelihood. Once, when a youngster, I had dug up and eaten ground-nuts, but they were gritty, tasteless things, and moreover I could only tell where they grew by the delicate white flowers which bloomed only in the spring. Nuts did not exist in this forest, or, if they did, they were not ripe at this season, and I therefore cast aside all ideas of securing a supply of vegetable food. Determined to try my hand at trapping and also to attempt to capture some trout, I started again for the brook, carrying a supply of hemlock roots and my spear. It occurred to me that by braiding fine roots together I could devise a fishing-line, but the question of a hook then confronted me and I decided to try my plan of bailing the water from a pool before experimenting with hookmaking.

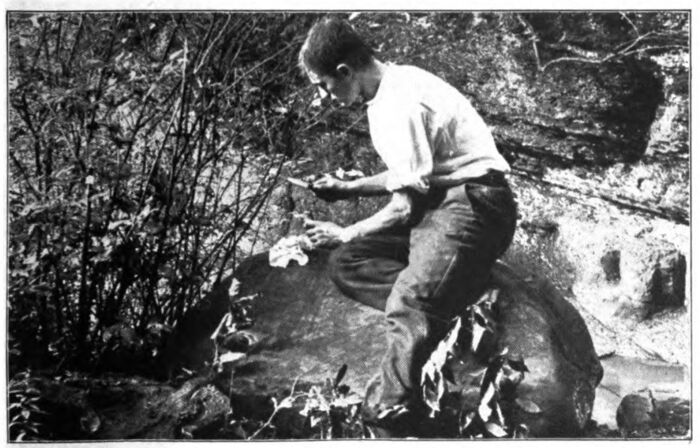

I soon found a pool containing several fine fish, and cautiously, for fear the trout might slip out among the stones, I piled gravel and small rocks in all the visible crevices which connected the pool with the running waters of the brook. This accomplished, I piled rocks across the little channel where the brook ran into the pool, and by chinking all the crevices with grass, twigs, and mud I at last had the satisfaction of seeing the water diverted to one side. The pool, with its fish, now remained cut off from the surrounding water, and all I had to do was to scoop out the contents, leave the trout floundering about on the bottom, and pick them up with my hands. This all sounds very simple and easy, but I had no scoop with which to bail out the water, and until I attempted the work I did not dream what a task I had set myself. I first tried bailing out the water with my hands, but as fast as I threw it out more oozed in through tiny crevices and I soon gave this up as impossible. Then it occurred to me that one of my shoes might serve as a dipper and, removing it from my foot, I tried to throw out the water by this means. I did succeed in making some progress, but very little, and I commenced to think that all my work had gone for naught when a bit of birch bark caught my eye and I had an inspiration. Many a time I had used birch-bark dippers and cups for drinking, when in camp with Joe, and I had seen boxes, packs, and other utensils made of the material. In fact, Joe had once proved to me that water could be boiled in a birch-bark dish, and I laughed to think how I had so far overlooked the manifold uses to which the bark could be put. It took but a few moments to strip a large sheet of bark from a convenient tree, and but a few moments more to bend this into a deep, boxlike form. The ends were easily secured by means of the hemlock roots, and with the bark dipper, which would easily hold a gallon of water, I proceeded to empty the pool. In a very short time the water was reduced to an inch or two at the bottom and the flashing, bright-colored fish were flopping about among the stones.

Four fine trout were the reward of my labors, and, placing them in my birch-bark dipper and covering them with cool leaves, I set them among the bushes beside the brook to await my return and then made my way toward the muskrat runway to set the trap.

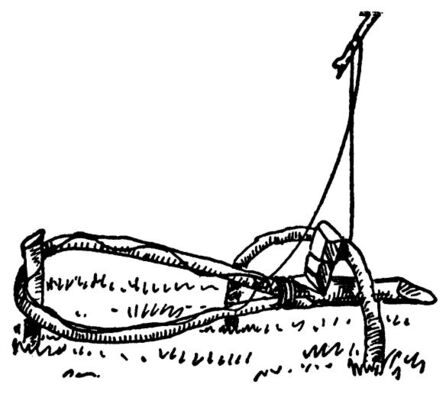

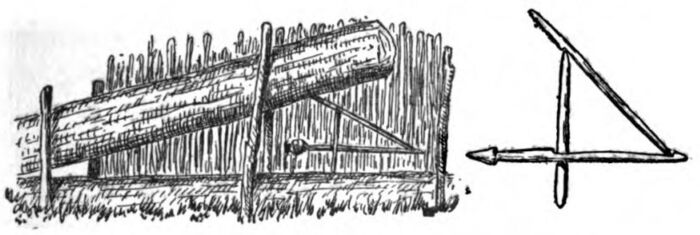

I did not know what sort of food the muskrat ate and I therefore decided to arrange a trap which would be sprung by the rat passing along the trail. First I placed a smooth stick of wood across the run, and on either side among the grass I drove two stakes with a space of a few inches between them. In this space I slipped a fairly heavy log which I found beside the pond, and I then lashed the tops of the stakes together so the log could slide readily up and down between the stakes which served as guides, and across the lashing of roots I laid a light stick. For a trigger I selected an “L”-shaped twig, and from one end of this I tied a strong root, with the other end of the fastening looped about the heavy log. This was adjusted until, when the trigger was placed across the light stick between the uprights, the heavy log was raised a few inches above the log set in the pathway. Next a very light stick was placed just above the lower log and the end of the trigger was placed resting against this, so that the pressure of the drop-log forced the trigger against the stakes. It was a very simple arrangement, but I knew that if any creature attempted to pass over the log upon the ground he would of necessity move the trigger-stick and allow the log to drop upon his back. The trap being set, I spent some time in securing a supply of frogs about the pond, and then started toward camp. I soon reached the brook and turned aside for the trout in their birch-bark receptacle, thinking with pleasurable anticipation of the fine meal in store for me.

I passed the pool, which was now rapidly filling up again, pushed aside the bushes, and gave a gasp of astonishment—the birch-bark dish was lying on its side, absolutely empty.

For a moment I was almost stunned by the discovery, but presently I realized that some prowling creature had robbed me of the fish which I had taken such pains to capture, and that I had only myself to blame for leaving the trout so carelessly within reach of any four-footed thief that might pass by.

It was a keen disappointment to be deprived of my expected feast, but there was nothing to be done save to drain another pool and capture more fish, if I wanted to eat trout that day.

I was anxious, however, to discover what manner of beast had stolen my fish, and I sought carefully in the soft earth and among the vegetation for signs of footprints. I had not long to search and soon discovered a number of tracks which I recognized as those of a fisher-cat, a large, marten-like animal which every woodsman knows for an inveterate thief. My first thought was to set a trap to capture the fisher, but, knowing the flesh to be unfit to eat, I abandoned the idea as a waste of time and trouble and set about my work of draining another pool. This time I selected a rocky basin worn by the water of the brook in the ledge itself—a sort of pot-hole—with solid walls which obviated the necessity of chinking up the openings and crevices as I was obliged to do in the pool I had drained before. With my birch-bark dipper the work of bailing out the pot-hole was simple and I soon secured a couple of good-sized trout.

With these and my frogs I dined well and decided to set forth on my tramp as soon as possible, for, now that I could obtain fish so readily, I had little fear of starving, for I knew that every brook and river in the forest swarmed with trout. I deemed it wise, however, first to wait until I could be sure of determining the exact points of the compass, and I also wished to determine the success or failure of my deadfall. Although the sun shone through the cleft in the forest formed by the stream, yet it gave me only a vague idea of direction, and while I knew by the sun that the river flowed in a more or less southerly course at this spot, yet I wished to familiarize myself with the various compass points and to discover some other means of distinguishing north from south and east from west, for I had little doubt that there would be many days on which the sun would not shine. Accordingly, on the following morning I started into the woods while the sun was yet low, to study and reason out any signs which would aid me in maintaining a straight course through the forest.

As soon as I was well into the woods I looked about with minute care for any details which would be of use and also examined the trees very carefully for moss and lichens, for, as I have already mentioned, I had heard that moss grew more abundantly on one side of trees than the other, but I had forgotten which side it was.

Nearly every tree was well covered with lichens and moss and I could not see that these growths were any thicker on one side than the other. I was about to abandon this scheme for determining direction when I made a discovery. Glancing up and down the trunks in search of the moss growths, I noticed that one side of every tree was dark-colored and damp, whereas the other side was grayish and drier, and the damp side I soon found corresponded to the north as determined by my glimpse of the sun above the river. I was quite elated by this and I now noticed that the mosses did appear heavier and more luxuriant on the damp side of the trees than on the dry side. A further scrutiny and comparison of the various trees also convinced me that the branches, twigs, and leaves were thicker and more regular on the south side of the trees than on the north, and that more dried and dead branches and stubs projected from the north side of the trees than from the south side. Fixing these facts in my mind, I determined to test my discoveries by actual experiment, and without looking at the tree trunks I wandered aimlessly ahead for several hundred yards. Then, closing my eyes, I walked slowly about for some time, bumping into numerous trees and tripping over fallen branches several times—until I felt that I had lost all sense of direction. Then, opening my eyes, I looked about. I was out of sight or sound of the river, the only signs of sunshine were faint, bright patches amid the lofty foliage of the trees, and nothing was in view which seemed familiar. For a moment my heart thumped and I shuddered to think what might happen if my signs failed and I could not find my way back to the river. It was a dangerous experiment, the peril of which I did not fully realize even then, but, pulling myself together, I focused my attention on the trees about me. There was no question about it, scarcely a glance was needed to show me which side of the trees faced the north and which the south, and, knowing that the river flowed to the east of the woods wherein I stood, I turned and started to retrace my steps. Even as I did so I realized how important was my newly acquired knowledge of this feature of woodcraft, for the direction which I had felt sure would lead me toward the river was exactly opposite to that which was shown to be right by the trees.

I was greatly pleased, for now I knew that in case rapids, cascades, or cliffs prevented me from following the river I could make detours through the forest, and, moreover, where the river turned and swung from its southerly course I could save miles of weary tramping by cutting across through the woods.

Thinking of such matters and only glancing now and then at the trees to assure myself of my direction, I was suddenly aroused by a large hare or rabbit which leaped from beside a dead stump almost at my feet and scampered off among the shadows. For a moment I stood still, watching the creature as he flashed across the open spaces and thinking regretfully what a fine supply of food was flitting beyond my reach. Then glancing down, I caught sight of a great mass of fungous growth upon the base of the stump from which the hare had jumped. The fungus was dull orange or yellow and grew in a form resembling sponge or coral. I had often seen the same thing before and had never given it more than a momentary glance, but this mass instantly riveted my attention, for one side of it had been eaten away and bits of the nibbled fungus were strewn upon the earth. This, then, was what the hare had been eating and I realized that by setting a snare or trap beside it I might be able to capture the rabbit. There was no time like the present for attempting the feat, and I at once set about preparing a trap. It was merely a simple “twitch-up,” such as every farmer’s boy uses for catching rabbits, partridge, and other small creatures, and while a few days before it would have been beyond me, it was now simple, with my knowledge of hemlock roots and the self-reliance which I was so rapidly acquiring.

Cutting a number of short sticks, I pushed them into the earth about the fungus, thus inclosing it on all sides but one. On either side of the opening thus left I drove two stout stakes with notches near their upper ends. From a bit of dead wood I then whittled out a spindle-shaped piece just long enough to reach from one of these stakes to the other. Then with a fine hemlock root I formed a noose, tied the spindle to the fiber just above it, and fastened the end of the root to the tip of a small sapling close by. Bending down the latter, I slipped the spindle into the notches in the stake, spread the noose across the opening, and my snare was completed. I was very proud of my work, simple as it was, and was quite confident that when the hare returned to finish his meal he would push his head through the noose, dislodge the spindle, and would be jerked into the air and killed by the spring of the sapling. I stood for a moment looking at the snare and the fungus and suddenly roared with laughter at my own stupidity. Here I had been working for nearly an hour to set a trap which might or might not catch the rabbit, and within a few inches was a supply of food of far more value and to be had without the least effort. Surely if a rabbit could eat the fungus, so could I, and I plucked a bit of the queer growth and tasted it.

It had a rather musty but not unpleasant taste with a slight nutty flavor, and I judged that, cooked, it might be very palatable. The question of eating mushrooms had occurred to me before this, but I knew nothing as to the edible qualities of fungus except that certain species were deadly and some nutritious, and I had not dared attempt eating them. Now, by the merest chance, I had discovered an edible species, and with a feeling of intense gratitude to the hare, I determined that his life should not be forfeited to my appetite and that he should be rewarded by being spared. Without more ado I removed the snare which I had taken so much trouble to prepare, and pocketed a large section of the fungus. That there was an abundant supply of this growth in the forest I was confident, and as I walked toward the river I searched on every log and stump for more. Several large masses were found, and, as many of these had been partly devoured by small animals, I felt reassured as to the edible and nutritious qualities of the sponge-like material.

I reached my shelter without further adventure and at once prepared to cook and sample the fungus. I was not at all sure as to the best method of cooking it, and decided to try a small quantity in various ways. I therefore placed a lump among the hot coals to roast like a potato, while another lump was hung on a green stick before the fire to broil.

Hitherto broiling and roasting had been my sole means of cooking food, but now, having remembered that Joe had once showed me how to boil water in birch bark, I made a rude pot of this material, placed water and fungus within, and set the whole over a bed of hot coals covered with ashes. The bit of fungus to be broiled soon shriveled up and was transformed into a leathery-like material, tasteless and useless, while the piece roasting in the coals sputtered and sizzled, and might as well have been a bit of pine bark at the end of a few minutes. Both of these methods were undoubtedly failures, and I watched with some anxiety the piece boiling in the birch-bark pot. When it had boiled for some minutes I fished a bit out and, as soon as it had cooled, proceeded to taste it. Much to my joy, it had quite lost its musty, woody flavor and was as sweet, nutty, and palatable as a boiled chestnut, and I at once drew forth all that remained in the pot and dumped in all I had left. Words cannot express the satisfaction I felt at thus having discovered a source of vegetable food which I could gather as I traveled along and which would assure me a supply of provisions without the trouble and labor of trapping animals, catching fish, or hunting frogs and mussels.

As soon as my meal of fungus was finished I arose and, taking my frog-spear, made my way to the brook and my muskrat-trap. It was with quite a little excitement that I pushed my way through the thick growth toward the runway where the deadfall was placed, for even with my newly acquired knowledge of edible fungus I felt that meat would be necessary, or at least welcome, during my tramp, and the success or failure of my first trap meant much to me. But I had no cause to worry, the deadfall had been sprung and had served its purpose well, for projecting from beneath the log was a furry head. Even before I reached the trap I thought it the largest muskrat I had ever seen, and as I stooped down to lift the log I uttered an involuntary cry of amazement. The creature I had caught was no muskrat, but a great, fat beaver. Truly, my first attempt at trapping had been a huge success.

Although I felt a hunter’s elation at having captured the beaver, he was really of less value to me than a muskrat. His flesh, especially his tail, was edible, I knew, but I doubted if I would care to devour his meat unless very hungry, for the scent and taste of castor would be too strong. His fur, although thick, was by no means in good condition, and even if it had been “prime” it would have been of little value to me in the forest, but, nevertheless, I foresaw that I might find use for skins, and very wisely, as it turned, decided to skin the creature and dry and preserve the hide.

While skinning the beaver I was attracted by the strong, white tendons of his legs and tail, and, knowing how useful such tough, thread-like material might prove, I carefully removed and washed the tendons and placed them in a safe spot to dry.

The beaver’s meat looked white, clean, and tender and I decided to cook and taste some of it. The tail I also decided to cook, for I knew the Indians and trappers considered beaver tails a great delicacy. The meat was placed to broil above the hot coals, and the tail, which seemed tough, was placed to boil in the birch-bark pot—or rather, in a fresh receptacle—for I found that after once using the bark for boiling it was worthless and that a new dish must be provided each time I wished to boil anything.

While the meat and tail were cooking I spread the skin of my beaver to dry and it then occurred to me that perhaps beaver flesh might be jerked or dried as well as venison. Accordingly, I cut strips from the carcass and hung them up. By the time this was done the meat was thoroughly broiled and ready to taste. Much to my surprise, there was but a very slight musky taste to the flesh, and while it was far from delicious without salt or seasoning, yet it was much better than mussels, and I greatly relished the flavor of real meat once more. The tail proved too gristly and tough to suit me and I doubt if I could have devoured it unless I were actually starving. It reminded me of pig’s feet, and I wondered how any human beings could like it. No doubt if properly prepared it might be far more palatable, but I then and there decided that beavers’ tails would be eliminated from my menu unless I was face to face with starvation.

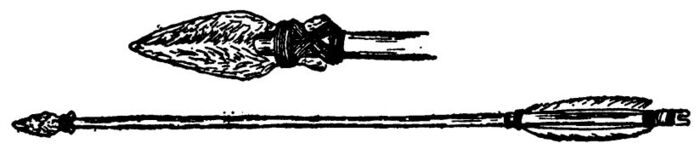

I was not sorry to discover that beaver flesh was edible, for I knew that where there was one beaver there were doubtless more, and that I might reasonably expect to catch others, but unless the meat could be dried and preserved it would be of little value for my purposes. I determined to try to dry trout. While thinking of this my mind turned to the matter of tackle with which to capture fish without the time and labor of bailing out the pools—a slow method at best and only possible where there were deep pools or basins. With the hemlock roots I could braid lines which I felt sure would serve my purpose, but I could not conceive of any way by which I could form a hook. I happened to notice the carcass of the beaver and picked it up to throw it into the river, when I noticed the sharp, chisel-like teeth and strong bones. For a moment I stood regarding them, turning over in my mind my various wants and striving to think of some purpose for which I could use either teeth or bones, for it seemed a pity to waste anything that might serve any useful purpose. I thought of fish-hooks, for I had heard of certain savage races using bone hooks, but I could not imagine a way of transforming either teeth or bones into trout-hooks, and I was on the point of throwing the body into the stream when bows and arrows again came to my mind, and instantly it occurred to me that the bones of my beaver might be sharpened and used for arrow-heads.

At any rate, it was a scheme worth trying, and I promptly began to dissect out the leg bones from the remaining meat. Lest I should want other material at some future time, I also removed and set aside the huge front teeth. This occupied a long time, and I had barely time to walk out to the trout-brook, catch two fish, after a deal of labor, and return to camp ere night fell. One of the trout served for my supper and the other was split, cleaned, and hung up to dry with the beaver meat.

The following morning I awoke to find the woods dripping and the world gray with a cold, drizzling rain. From my fire a thin, blue wisp of smoke arose, and I hurried to replenish the fuel and save the little life there was left in the embers. Before I could fan the coals into flame the lowering, gray sky poured forth a torrent of rain, and with a faint hiss the last hot coals grew black and dead.

Soaked through, chilled, miserable, and disgusted, I crept into my hut and, seeking a sheltered spot, sought to secure another fire with my knife, pebble, and handkerchief. What was my disappointment to find the handkerchief damp and soggy with moisture, and while one or two spots appeared quite dry, my utmost endeavors failed to ignite the cotton cloth. For an hour or more I labored, until my hands were cut and bleeding and the back of my knife-blade was worn rough and battered, and then, thoroughly disheartened, I gave up in despair. Hungry as I was, I had nothing save uncooked fungus to eat, for I had not yet reached the point where raw mussels, raw frogs, or raw fish could be considered.

Sitting in the partial shelter of my lean-to, I spent a dreary and forlorn morning, for while the roof was fairly tight the rain drove in at front and sides, and only in the very center of the hut could I remain fairly dry. My wet clothes clung to my skin, chilling me to the bone each time the cold wind whistled down the river, and my reflections were far from cheering, for I knew that this was but a sample of what I might expect. Summer was over and the autumn rains had begun, and in a few weeks more icy winds and snow-squalls would succeed them. With a roaring fire all might have been well, and I could have laughed at the elements, but without fire I realized how helpless I was and ever uppermost in my mind was how to safeguard myself against the loss of my fire in the future, provided I again succeeded in starting a blaze—something which I considered very doubtful.

Toward noon, however, the rain ceased, the sky cleared, and by mid-afternoon the sun was shining brightly. I lost no time in finding a sunny stone whereon to spread my handkerchief, and as soon as the bit of cloth was dry I again essayed to ignite it with a spark from my flint. This time I met with more success, and after several trials I obtained a blaze and soon had a roaring fire. As soon as the fire was burning well I cooked food and while this was being done busied myself in making a neat, tight box or case of birch bark in which to carry my handkerchief. I was fearful lest the cotton cloth should give out long before I reached the end of my journey, for only a small portion remained intact. To provide against such a loss I tore bits of cloth from my shirt, charred spots on the strips with coals from the fire, and packed these carefully in additional birch-bark receptacles. To make doubly sure that these were water-tight, I smeared the edges of the packages with pitch, as I had seen Joe repair rents in the canoe, and having thus provided against future showers as far as was possible, I sat down to my meager meal and the world and my future took on a more roseate hue. While I was fireless during the forenoon I had determined to try a bow-drill and spindle for making fire, for I felt that if I could obtain the proper materials this would be a far easier and quicker way of making fire than by flint and steel, which could be reserved for emergencies.

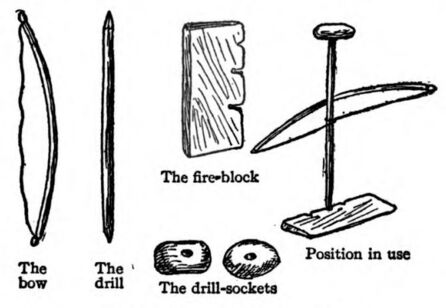

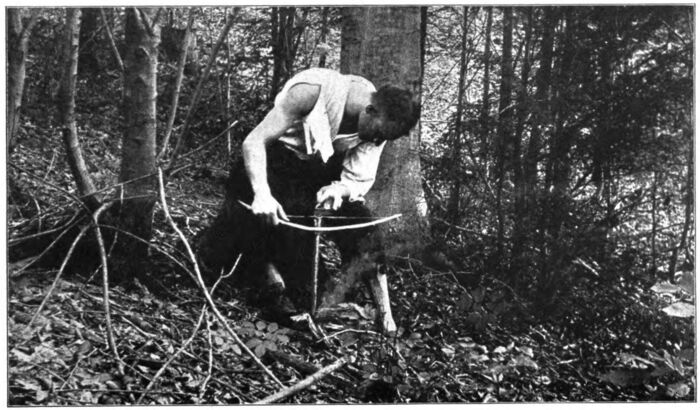

With this object in view I entered the woods and searched diligently for materials for my fire-making apparatus. As I have already mentioned, I had made fire by this crude, savage method when a boy and I knew by experience the materials best suited to the purpose.

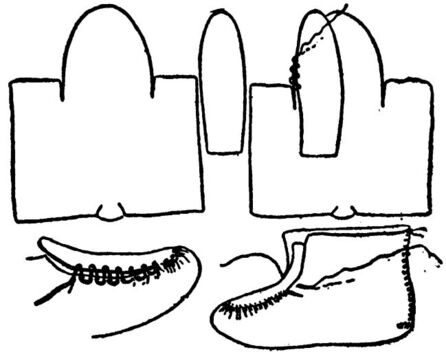

The bow was an easy matter, for spruce was as good as anything, and this tree was abundant everywhere. While cutting the bow for fire-making I remembered my determination to attempt the manufacture of bow and arrows and I selected several likely-looking spruce boughs for this purpose. I next looked about for a suitable stick for the drill and selected some straight, old, dry fir roots from a tree which had been torn up and blown over by some winter’s storm years before. A piece of the dry, weathered wood from the same tree served as material from which to make a fire-block, and from beneath the bark of a dead pine I secured a good supply of “punk.” A hard pine knot was selected for a drill-socket, but despite every endeavor I could find nothing which I was sure would serve as tinder. Shredded cedar bark I knew was as good as anything, but not a cedar could I find, and finally I decided to try the thin, papery, dried birch bark which flaked in little curling rolls from the trees. Armed with these various things, I returned to my lean-to and was soon busily preparing the materials for use. The flexible, springy spruce limb was whittled down to a rude bow, and not until then did I remember that all my youthful attempts at thus making fire had proved failures until I used a leather bowstring. For a moment I was nonplussed, for leather was out of the question, until I thought of my shoe-laces. One of these was sacrificed and replaced by hemlock roots, and I then whittled down a fir root into a double-pointed, octagonal spindle about fifteen inches long. With the tip of my knife-blade I dug out a recess in the pine knot and whittled the outside to fit easily in my hand and then turned my attention to the fire-block. A piece of the dry, seasoned fir was split into a little slab about three-fourths of an inch thick with notches cut along one edge, and I was ready for my experiment at fire-making.

Upon a smooth, dry stone I placed a piece of the dry pine punk, with another piece close at hand. Next I set the fire-block upon the piece of pine and with the bowstring took a turn about the center of the drill. Setting one end of the drill in a notch of the fire-block, I placed the drill-socket, made from the knot, upon the other end of the drill, and steadying the fire-block with my foot I pressed firmly down upon the socket with my left hand and drew the bow back and forth with my right hand. With even, steady strokes I whirled the drill around and around, and presently a little mound of brownish, powdery sawdust began to accumulate on the punk beneath the fire-block. Gradually the pile increased, the hole made by the drill in the block grew larger and larger, and a faint smell of scorching wood greeted my nostrils. Harder and harder I pressed down on the socket, faster and faster I twirled the drill, and an instant later the sawdust turned black and a slender column of smoke rose from it. Dropping drill and bow, I stooped and blew gently on the smoldering powder, and as the smoke increased I lifted the fire-block from the punk beneath, slipped a few bits of the papery birch bark into the powder, clapped the second pine punk on top of all, and, seizing the whole in my hand, waved it swiftly back and forth. Hardly had I swept it through the air when the bark burst into flame, and, knowing success was mine, I danced and capered about, as pleased as the first time I had accomplished the feat, years before. The tinder, punk, fire-block, and socket were inclosed in birch-bark packages, the drill and bow were laid carefully in the roof of my hut, and I felt sure that I would be able at any time to secure a fire in dry weather and, unless soaked with rain, that I could be reasonably sure of kindling a flame even in wet weather—for I now had two distinct methods of obtaining fire.

My fire-making apparatus was such a success that I was anxious to go ahead with my bow and arrows, and I spent a long time scraping and whittling down the best of my spruce branches to form a bow. The ones I had selected were dead, seasoned limbs, for I well knew that green wood would warp and would have a very limited spring. At last one of the boughs was fashioned to suit me and I looked about for a bowstring. Hemlock roots seemed the only available material and a long time was spent in braiding enough of the fine roots together to form a string for the bow. Eager to try the new weapon, I cut a notch in one end of a fairly straight stick, placed it on the string, and drew the bow. As I released the string the bow sprang straight with a delightful “twang,” and the stick went humming through the air, but with a loud snap the string parted. I was so greatly pleased at the strength and elasticity of my bow that the mere matter of the parted string troubled me very little, for I felt confident I could make some sort of a cord which would be strong enough for the purpose and I dropped my bow and hurried into the woods to search for suitable sticks from which to make arrows. Sticks there were in plenty, but, although I sought everywhere, I was unable to find one which was really straight and smooth. Cutting the best I could find, in the hope that I might be able to whittle them into presentable shape, I made my way back to camp.

I was exceedingly hungry, and with my mind on food I examined the beaver meat and fish which I had hung up.

It was an ill-smelling mess, and without more ado I cast it into the river and dined on mussels and fungus, for I was too tired to attempt a trip to my frog-pond or the brook. The next morning, however, I visited the brook and my deadfall, but the latter was empty, although sprung, and I failed to secure a single trout. The reason was simple. The brook had been so swollen by the recent rains that it was impossible to dam up any of the pools, while the pond was filled to overflowing and only one small frog could be found by dint of the most careful search. Despite my ill luck, however, I returned to camp quite elated, for while making my way about the little pond in search of frogs I had discovered some thick bushes with reddish stems so straight, smooth, and polished that they at once struck me as being perfectly adapted for arrows. Not until long afterward did I learn that this bush was known as “arrow wood” and that the Indians formerly used it for their arrows.

With a supply of this useful bush I busied myself at arrow-making, for although I had no feathers I thought that I might be able to make arrows which would serve to kill the tame and unsuspicious birds and animals, and I had but to kill one large bird in order to obtain feathers to make better arrows. Several times I had seen partridges or grouse, and on one or two occasions I had attempted to snare them by means of a hemlock-root noose on the end of a light pole, but the material was too coarse for the purpose and the birds invariably avoided the snare. Once or twice I had attempted to kill them with stones or clubs, and once I had even thrown my spear at them, but in every instance they had escaped. Perhaps it was the season, perhaps the birds were suspicious of the first man they had seen, but whatever the reason, the fact remains that they were far wiser and more wary than the grouse I had often seen when hunting in Joe’s company.

It was a simple matter to cut notches in one end of each arrow, but it was a far more difficult job to fit heads. The beaver’s bones were the only material I had for this purpose and I found it hard work indeed to cut and sharpen these into any semblance of an arrow-head. Indeed, I found it so difficult that I even sought to chip arrow-heads from the pebbles of the river, but I had not the remotest idea how stone arrow-heads were made and my efforts in this direction resulted only in bruised fingers and irregular, broken stones of no earthly use for my purpose.

By dint of hard work and the expenditure of many hours I finally cut and ground down some bones until they had sharp points at one end and a recess at the other, and to these I bound my arrow sticks with the sinews taken from the beaver. I still had a bowstring to make, and as I worked away at the bones I busied my mind trying to invent some sort of cord which would stand the strain of the bow. I thought of the tendons of the beaver, but these were neither long enough to serve the purpose nor were there enough to braid together to form a string, and I was at last compelled to fall back upon hemlock roots. An examination of the broken bowstring revealed the fact that it had parted at the knot at one end, and to avoid this I decided to braid or lash a loop in the new string. I made this new cord much heavier than the old, selected the fibers with greater care, and smeared the whole with pitch. The loops at the ends were twisted in and lashed in place with tendons, and when all was done I drew the bow with some trepidation for fear all my hard labor would be wasted. Much to my satisfaction, the string withstood the strain and I practised until dark with straight sticks which had bits of stone gummed on with pitch for heads, and I found that up to twenty feet I could frequently hit a mark the size of a partridge.

Anxious to test my weapons on real game, I arose early the following morning and entered the woods in search of partridge. I soon flushed a flock of grouse from among the young fir-trees, and as they perched upon the branches and craned their heads to view the intruder I approached closely, placed an arrow on the string, drew the bow, and let drive. I doubt if I was a dozen feet distant from the birds and they were packed so closely together on the branch that I could scarcely have missed them, but when the bone-tipped stick struck one of the grouse in the breast and with a great flapping he came tumbling to earth, I felt as if I was the most marvelous archer in the world. As the partridge fell the others took wing and whirred out of sight, but I paid little attention to them and hurried to pick up my first feathered game. The arrow was still sticking in the bird’s flesh, although the stick had been broken in his fall, but the head was the only valuable portion, and I hurried back to my fire, happy in the thought that I now had a weapon with which I could actually kill game.

The wing-feathers of the grouse were carefully saved, and after I had dined from the delicate meat and had picked every bone clean I devoted all the rest of the day to feathering and pointing my arrows. How to carry them was the next question, and here the beaver skin came into mind. I was learning rapidly to think out and to find ways and means, and was acquiring a store of useful knowledge, and I smiled to myself as I thought how far better equipped I was to make my journey out of the woods now than I would have been when first I scrambled out of the river not so many days before.

The beaver’s skin furnished an excellent quiver, or case, for my bow and arrows, with plenty of room for a supply of mussels and fungus, and my fire-bow and drill in addition, and as there was nothing more to detain me here I decided to start on my tramp the next morning.

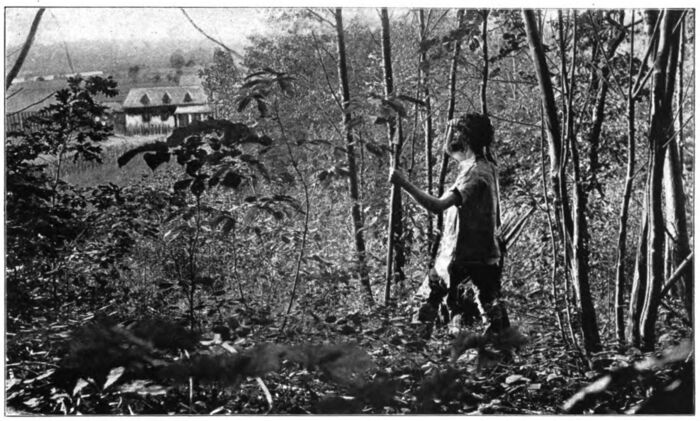

I ate a plentiful breakfast of fungus and mussels, and then, with the skin filled with my possessions on my back, with pockets bulging with hemlock roots, tendons, bones, and flint, and with a number of mussels and some fungi tied in a bundle in one hand, and my frog-spear in the other, I set out on my long tramp. As I reached a bend of the river and glanced back for a last look at the little lean-to beside the river, I felt as if I was leaving home. The wilderness had been kind to me and I had fared far better than I had dared hope in this spot. As I turned again toward the south and picked my way along the river-bank, little did I dream what fate had in store for me or how many dreary months would pass ere I reached my goal.

All day long I tramped onward, following the course of the river, but frequently entering the woods and trudging through the forest for several miles to avoid impassable portions of the river-bank. Quite frequently the shores rose in steep, rocky bluffs, between which the torrent roared and foamed, while at other times fallen trees, driftwood, and logs made progress along the shore impossible. Many a time that first day of my journey did I have cause for thankfulness that had taken the precaution to learn means for determining the points of the compass, for the knowledge saved me many a weary mile.

Late in the afternoon I made camp at a little cove where the river cut into the woods and where a crystal brook babbled through a fern-grown ravine and gave promise of trout and frogs. My first work was to build a tiny lean-to, and in doing this I saved myself a deal of labor by using dead and fallen branches for the timbers of my shelter instead of cutting them from living trees. I soon started a fire, and then walked up the brook in a search of game. I had expected to find a few frogs or perhaps to obtain some trout, but presently a flock of grouse whirred up from the ferns and alighted on a low spruce a few yards away. It took me but an instant to fit an arrow to my bow and to let it fly at one of the birds. I made a clean miss and, rather chagrined, I tried again. Once more I missed, but the stupid birds remained motionless and not at all frightened by the passing arrows. As I watched them and wondered if it would be possible to approach more closely I remembered the beaver sinews and determined to attempt snaring the grouse. Rapidly forming a noose with one of the fine tendons, I attached it to the butt of my frog-spear and cautiously crept toward the unsuspecting birds. When within reach I slowly pushed the pole forward, and although the grouse craned their necks, moved about a little, and showed some nervousness, they remained upon their perches, and an instant later the noose was slipped over the head of the lowest and with a quick jerk I brought him fluttering to the ground. Even then the other birds did not take flight, and three fine grouse were mine ere the others realized their danger and winged their way to safer quarters. I was greatly elated at my success and dined royally on partridge, and had enough left over for my food for the next day.

As I sat by my fire that evening I thought over my life since the day when I was cast into the river, and, much to my surprise, I found it difficult to fix the days and the sequence of events in my mind. Then for the first time I realized that if I was to keep account of time I must devise some means of recording the days.

My first idea was to cut notches in a stick, one for each day, but I at once gave this up as impracticable, for I foresaw that the numerous notches representing the days I had already passed in the woods would prove confusing, and that this method would merely enable me to tell how many days had passed and would fail to give me an idea of the day of the week or the month. Moreover, to carry sticks for this purpose would be a nuisance, and after some time I decided to make a rude calendar by means of beaver tendons. My scheme was very simple and consisted of using two tendons, one for the week-days and the other for the months. Each day I would tie a knot in the week string and when the seventh day was reached I would tie a large knot. Then when the days made up a month I would tie a knot in the month string. To think was to act, and selecting a smooth, long tendon I tied knots to represent the seven days I had already been in the forest, with the last knot double the size of the others, and as the canoe had been wrecked on Wednesday, the 2d of August, I tied nine knots in my month string, which gave Wednesday as the day of the week and the ninth day of the month as the correct date. I could easily remember the month itself and I had not the least expectation of being in the wilderness long enough to require a means of keeping track of future months, but as it turned out, many a month string was tied into knots ere I came to my journey’s end.

For several days I tramped onward without adventure or incident, save that I fared ill for meat and was obliged to depend almost entirely upon the mussels in the river and the fungus in the woods. Over and over again I gave thanks to the rabbit which had first led me to this supply of food, for without the fungus I would have gone to bed hungry on many a night. Several times I saw hares and once or twice I flushed partridges. I repeatedly tried to kill these creatures with my bow and arrows, but I failed each time. Moreover, the grouse seemed wild and suspicious and I could not approach closely enough to snare them, while the brooks I passed, although alive with trout, had no deep pools or isolated basins which I could bail out to secure the fish. Anxious as I was to get out of the woods without delay, my longing for better food finally overcame my impatience and I decided to make a halt for a day and endeavor to trap or snare some sort of game.

Accordingly, I made camp at midday and spent the afternoon preparing twitch-ups and deadfalls. It was while setting one of the latter that an accident gave me an idea which proved of the utmost value and made my lot far easier. Bending over and endeavoring to lift a log, my belt parted, and to my chagrin I discovered that the stitches which held the buckle had ripped out. Holding it in my hand and thinking of a way of lashing it to the leather again, it suddenly occurred to me that in this bit of metal I had the means of fashioning a fish-hook. The buckle was a fairly large one, with a strong, sharp tongue, and one end of this was already formed in an eye. All that was necessary was to detach the tongue from the buckle-frame and bend it into a hooked form. Instantly the deadfall was forgotten and I set to work hammering the buckle with stones and bending it back and forth in order to remove the tongue.